By Maria Wiering

Beginning well before he was elected pope in 2005, Pope Benedict XVI made substantial contributions to theology and Catholic thought through his prolific writing, academic lectures and long-form interviews, said scholars who study his work. In the wake of his death on 31 December 22022 and funeral in St Peter’s Square on 5 January, Benedict has been heralded as one of the most important theologians of the 20th century, one whose scholarship will stand the test of time.

Pope Benedict was “very intellectually gifted,” said Tracey Rowland, a theologian at The University of Notre Dame Australia and author of “Ratzinger’s Faith: The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI,” published in 2008 by Oxford University Press.

“He was a great gift to the church, and I think in the future, he will be a doctor of the church,” she said. “In a hundred years’ time, he will be seen to have laid the foundation for a theological renewal.”

Even before he attended the University of Munich, Joseph Ratzinger was well educated in the classics – the literature of ancient Greece and Rome – and had studied Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

“He comes out of that German intellectual tradition, and that was the most demanding scholarship in the world,” Rowland said. “What you ended up with was this man who was really atop the whole grip of the Western intellectual tradition.”

Ratzinger wrote his 1953 dissertation on St Augustine of Hippo. And he wrote a second dissertation-level work, qualifying him to teach at a university, on St Bonaventure. Both doctors of the church were major influences in his thought, Rowland said: St Augustine shaped his view of ecclesiology and the relationship between love and reason, and St Bonaventure shaped his understanding of revelation.

Then-Father Ratzinger taught dogma and fundamental theology at four German universities: Bonn (1959-1969), Münster (1963-1966), Tübingen (1966-1969) and Regensburg (1969-1977). At Regensburg, he also later served as dean and vice-rector until his 1977 appointment as archbishop of Munich and Freising.

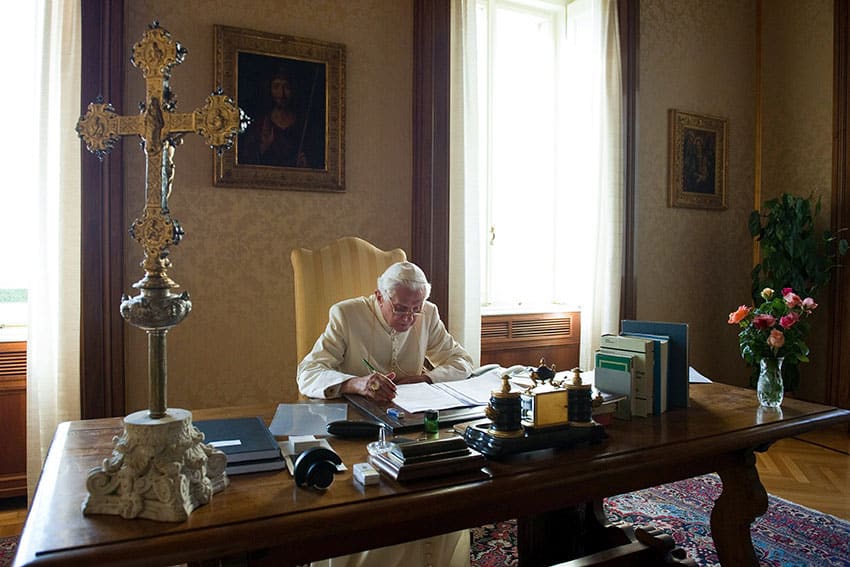

Father Emery de Gaál, chairman and professor of dogmatic theology at University of St Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary in Mundelein, Illinois, described Pope Benedict as a scholar who surrendered his whole life to academic work. He authored “no less than 1,600 theological titles, books, articles, essays, book reviews,” Father de Gaál said. Among those works is the 1968 book “Introduction to Christianity,” which has been widely translated and called a “masterpiece.” He also oversaw the compilation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, published in 1992, under Pope St John Paul II.

“He stands in a singular position as a theologian pope. No pope has written that much and so much in an original and decisive way,” Father de Gaál said. “To see a pope with comparable theological acumen, we would have to go back to Gregory the Great in the sixth century, or Leo the Great (in the fifth century). And, of course, they didn’t write that much.”

During the Second Vatican Council, the future pope served as a theological adviser and was among the theologians considered to be “reformers.” He was a contributor to and editorial board member of Concilium, a theological journal launched in 1965 by Vatican II standouts, including Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx and Hans Küng. However, in 1972, Father Ratzinger helped to found the competing journal Communio with Hans Urs von Balthasar and Henri de Lubac.

Change in theological outlook doubtful

Some observers say his theology pivoted from “progressive” to “conservative” around 1968, as cultural upheaval overtook European university campuses due to the Vietnam War, sexual revolution, rise of Marxism and attacks on the Western intellectual tradition.

However, other scholars disagree, arguing that Pope Benedict’s scholarship is theologically consistent. Rowland said the “tsunami in the 1960s” didn’t shock the priest-professor, but he rejected the stance some Church leaders took to “adopt the spirit of the times and try to market Christianity” to it. Instead, Ratzinger argued that the Church was not a “haberdashery shop,” where the windows change with the fashion, she said.

“At the Second Vatican Council, he was part of the reform group, but he was never … theologically liberal,” she said. “He was in favour of reform because he wasn’t in favour of 16th-century Baroque scholasticism. He was more patristic, more Augustinian. What happens in the late 1960s and the early 1970s is that there was a split among the reformers. So, the people who had been the reformers at Vatican II break into two camps and one becomes very liberal” on matters such as morality and restructuring church governance, she said. “Ratzinger never had those ideas.”

‘Not the Ratzinger he was made out to be …’

Father de Gaál said the political categories of “liberal,” “progressive,” “conservative” or “restorative” he’s seen applied to Pope Benedict in the wake of his death are inaccurate descriptors. Because of divine revelation, “to speak of ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal’ is really a caricature. … You really have to go into the nitty gritty of theology, of the Catechism, of Scripture to discover that men and women of all faith, be it simple or sophisticated, rise above such categories.”

As prefect of the Congregation (now Dicastery) of the Doctrine of the Faith from 1981 until his papal election, then-Cardinal Ratzinger had the job of defending Church doctrine, a role that earned him the moniker “God’s Rottweiler.” Because of that public perception, Christopher Ruddy, associate professor of systematic theology at The Catholic University of America in Washington, said he was pleasantly surprised when he began reading Ratzinger’s writings, including his memoirs Milestones, in the late 1990s.

“I found that this was the theologian who was speaking to my heart,” he said. “I’m like, ‘This is a very different person than I’ve been led to believe that he is.'”

Real works of faith

Ruddy, who teaches a course on Pope Benedict, said then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s 2000 book The Spirit of the Liturgy – a complement to the 1918 same-titled work on liturgical renewal by Romano Guardini, a priest-theologian whom Ratzinger knew and admired – will likely prove to be his most influential.

It presents the liturgy as “not something that we do once a week or once a day or so on, but that our entire lives are meant to be liturgical, and that what we’re most ultimately made for is to worship God, to praise him, and in doing that, to become fully human and fully alive,” Ruddy said.

He also praised Pope Benedict’s three-volume Jesus of Nazareth, published in 2007. The work conveys that “he’s not just believing in some system of thought or practices … but he actually wants to see the face of the Lord,” he said. “These are real works of faith, and I found that very inspiring.”

Enyclicals in the pastoral key

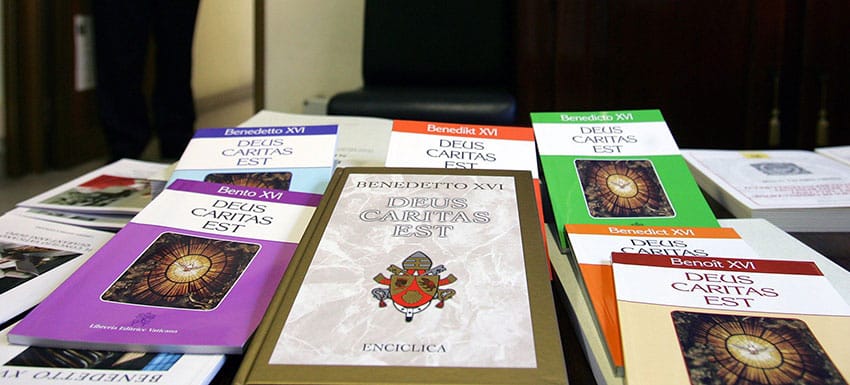

As pope, Benedict wrote three encyclicals, or letters to the church: God is Love (2005), Saved in Hope (2007) and Charity in Truth (2009). John Cavadini, a theology professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana in the US, said that with the encyclicals, Pope Benedict is “taking up a very basic facet of our faith … and explaining it to people.”

The encyclicals revisited some themes Pope Benedict explored in earlier works, said Cavadini, whom Pope Benedict appointed in 2009 to a five-year term on the Holy See’s advisory International Theological Commission. For example, Saved in Hope (Spe salvi) drew on his 1977 theological treatise Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, which examined, but in a more “theologically detailed and technical” manner, Cavadini said, the four last things: death, judgment, heaven and hell. The encyclicals are written to be more accessible to Catholics “in the pew” and reflect Pope Benedict’s pastoral concern.

That’s also reflected in Pope Benedict’s admonishment of what he termed “the dictatorship of relativism” to describe nonbelief in ultimate truth. Pope Benedict argued that “If you don’t believe in anything absolute, then you don’t believe in love,” Cavadini said, and for Pope Benedict, “eternal love and eternal truth (Jesus) are the same thing.”

The personal-pontifical tension

One challenge Pope Benedict faced as pope was a seeming desire, at times, to separate his own writings from his papal teaching function, said Kurt Martens, a canon law professor at The Catholic University of America. In his introduction to Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict said that the work was not an exercise of his teaching authority but was from his private search for God.

“That begs the question: To what extent, when you hold that office, can you write as a private person?” Martens asked. “I don’t know the answer to that.”

Meanwhile, a 2006 lecture Pope Benedict gave at the University of Regensburg incited street protests in some Islamic countries because he quoted a Byzantine scholar critical of spreading the faith through violence in Islam as being incompatible with God’s nature. Martens said the lecture was academically unproblematic, but it was criticised because it was delivered by a pope, not simply a scholar.

Benedict the ‘Bridge’

Speaking in general of Pope Benedict’s papacy, Martens described him as a “bridge” between St John Paul II and Pope Francis, who was elected in 2013 after Pope Benedict’s resignation.

“John Paul II was more of a doer, and Benedict the thinker. Francis comes with a more pastoral approach, that idea of the church as a ‘field hospital,'” he said. “I think Francis would not have been possible without his two predecessors.”

Father de Gaál said he expects interest in Pope Benedict’s scholarship to grow as more of his works are translated from German into other languages, including English.

“The more distance we gain from the cultural context in which Pope Benedict wrote in the 1950s, 1960s, 70s and onward, the more we see his theology as self-standing, and thereby being classic,” he said. “It speaks to every generation.”

Related