In this week’s edition of the paper, Marilyn Rodrigues has written about the submission to the inquiry on legalising mitochondrial donation in Australia from Bishop Richard Umbers, on behalf of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference.

Our federal MPs will be given a conscience vote on whether mitochondrial donation should be legalised, and so we should be reaching out to our federal MPs to make sure they know the views of their electorate on this important ethical issue.

Without wanting to get too technical about it all, understanding the science behind mitochondrial donation is important in understanding its ethics, because – like often happens with problematic medical interventions – friendly-sounding euphemisms are used to mask what is actually going on.

In this case, talking about “mitochondrial donation” evokes ideas of organ donation and other altruistic actions, disguising the destruction of embryos and cloning techniques that it actually involves.

Mitochondrial donation aims to provide a remedy for mitochondrial disease, a nasty form of genetic illness passed on through the mother.

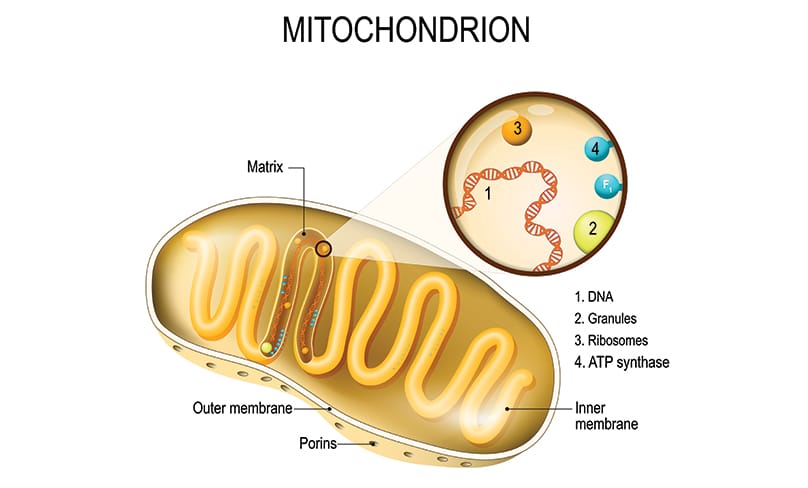

It comes from the mother because, in addition to the 23 chromosomes that are contained in a non-fertilised ovum, there is a small amount of DNA contained in the mitochondria, which are located in the part of the ovum surrounding the nucleus. Problems in this “mitochondrial DNA” can cause certain genetic diseases, with some of these causing death of a child in infancy.

Mitochondrial donation involves two different ways of replacing the mitochondrial DNA from the intended mother with that of a donor, both using IVF techniques and both involving the creation of babies with three genetic parents.

The first method is pro-nuclear transfer. In this method, each of the ova from the intended mother and the ova from the egg donor are fertilised with sperm from the father, using IVF techniques. The nucleus of the embryo created with the ovum from the donor is removed, destroying the newly-created life within it.

The nucleus from the embryo created with the egg from the mitochondrial disease-affected mother is also removed, leaving the unhealthy mitochondria behind, and transferred into the “healthy” ovum.

Pro-nuclear transfer always involves the destruction of at least one unborn human life, and probably many more than this, given that numerous eggs would be fertilised simultaneously. There is also a concern that this type of method is the same technique that is used in human cloning, which is obviously against the law as well.

The second method, maternal spindle transfer, follows the same method but removes the maternal chromosomes from each ovum before they are fertilised. This process, then, does not necessitate that a human embryo is destroyed in the process, but it would likely happen in practice, given that more embryos will be created by this method than will ever be used.

Even if we leave aside the ethical issues that arise from the process in which these embryos are created, there are still many, many reasons why this is problematic.

First, it is not providing a cure for mitochondrial disease. All it is doing is trying to make sure that children with these types of diseases are never born: it is a eugenic –not a therapeutic – endeavour.

Second, we have no way of knowing what the effect of having three genetic parents will have on the child, or on future generations. Earlier methods of trying to treat mitochondrial disease, such as injecting mitochondria from another woman into the ovum, resulted in babies being born with a greater risk of other genetic diseases.

Even the consultation paper released from the Department of Health states that: “Immediate and long-term risks for the child and longer term implications for subsequent generations are not yet fully understood.” In other words, they are confident that they can have the child born but after that, this so-called treatment is experimental.

Third, these unknown risks are completely unnecessary. A donor egg could just be used and a normal IVF process occur. Even though we don’t agree with the ethics of IVF, it is already legal and extremely prevalent, and doesn’t hold the same risks to the child born and to future generations as the mitochondrial donation process. Couples affected by this could also seek adoption of foster care as other forms of parentage.

The only reason the Government is considering exploring this very risky procedure is so that the child’s mother whose own mitochondrial DNA is affected can have a baby who is biologically related to her.

While wanting your own, biological child is an understandable and even commendable desire, it should not come at such great a risk to the child so born and future generations.

This brings us to the fourth risk: it’s not unthinkable that this procedure, once perfected, will be expanded beyond those affected by mitochondrial disease to other groups.

In particular, I can imagine that the ability to create babies with two mothers, both of whom are genetically related to the child, will be immensely attractive to same-sex couples, and there will be pressure to extend “mitochondrial donation” to those couples as well.

If we want to stop this unethical and unnecessary, risky eugenic process from occurring, then we need to be letting our federal MPs know that we don’t want it in Australia. Why don’t you pick up the phone or write a letter to yours today?

Related: