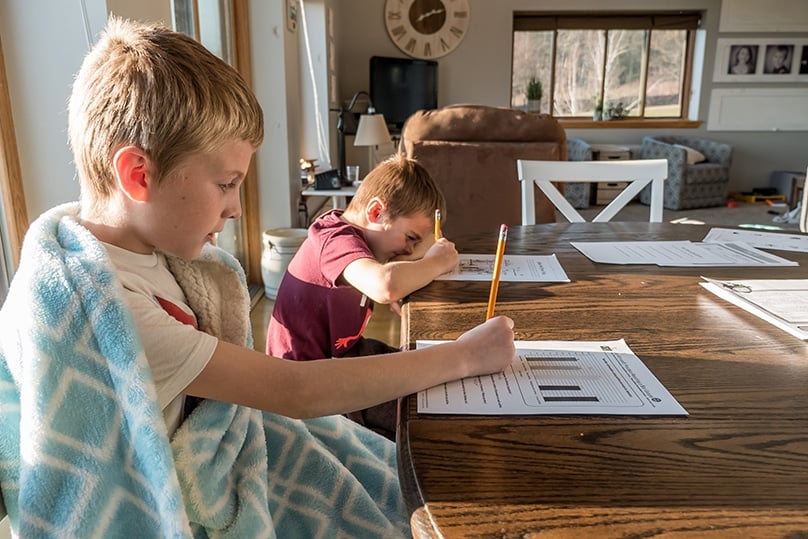

When my family used to homeschool, I used to interrogate myself about which was be worse: The horrible knowledge that I was in charge of everything they would learn that day? Or (if we switched to someone else teaching) the horrible knowledge I wasn’t in charge of anything they would learn that day?

It was very hard to get used to sending my kids off for six or seven hours a day, and not really know what they were learning. Now that I’m used to it, I can see that some of it is great, some of it is fine, some of it is terrible, and some of it is just baffling. The thing is, I never really know how much I know. All I know is what the kids choose to tell me, or what I can figure out.

This is true for every parent who is not physically sitting on top of their child twenty-four hours a day. All you know about what your kids are learning is what you are allowed to know, by the people your kids come into contact with, and by your kids. That is the nature of kids growing up.

Right now, there is a case working its way through the courts in the US about whether or not parents should be able to get their kids to opt out of learning with books with LGBTQ+ themes. The problem with stories like this is that, reading it, I don’t really know what these books are. The article says the parents who are suing object to “LGBTQ+ inclusive books.”

It mentions, “Some of the books at the centre of the clash include Pride Puppy, geared toward preschoolers and Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, geared toward students in kindergarten through 5th grade.”

You get the general impression from reporting on such stories that the parents are opposed to these books solely because they include LGBT people. This may be the case, but I have read numerous stories phrased identically to this one that, when you drill down into the facts, are revealed to deliberately mention one title but not another, or excerpt one page but not another. It’s hard not to conclude that the goal is to make the parents appear foolish and bigoted. It’s hard not to conclude that the article is complicit in hiding something from the general public.

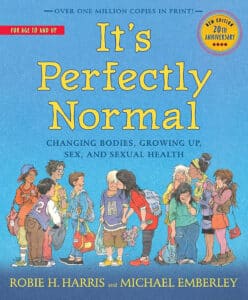

Slate magazine—hardly a mouthpiece for conservative, reactionary parents—recently published a story about this very phenomenon, in which the author admitted that he thought it was overblown hysteria when people objected to the popular sex ed book It’s Perfectly Normal. But when he saw the actual copious and explicit drawings of intercourse, masturbation, and genitalia designed for ten-year-olds to pore over, he was taken aback.

He was left asking himself, is this perfectly normal? Is it really okay for little kids to be staring at detailed renditions of people pleasuring each other? It does not seem okay! And yet he had assumed, based on the way the book had been covered in the news for years, that parents who objected were just pearl-clutchers who wanted their precious kidlets to believe babies came from the stork.

So that’s one problem. When books are challenged, the full list of book titles, and the full scope of the content that’s being challenged, often gets deliberately left out of the news coverage. The other problem is that, even if you know down to the ISBN which books and materials are being used in your kid’s classroom, that doesn’t necessarily tell you the first thing about what your kids are really learning in school, because books aren’t the only way kids learn. Far from it.

Here’s an example: One year, a staff member at my kids’ school quietly took me aside and reminded me that, at this school, the teachers had a policy to avoid discussing controversial political topics with the kids. They thought it was best to leave such conversations to the parents. That being the case, they were asking me to ask my child not to wear her pro-life t-shirt to school anymore. I thought this was reasonable, and happily complied.

I did not feel that our free speech or our liberty were being suppressed; I saw that it was a broad policy that was being carried out impartially. I felt pretty capable of conveying our pro-life principles to our kids without the aid of that particular shirt. And she was free to talk to her friends about her views; it just wasn’t supposed to be discussed in the classroom.

The very next year, a different teacher introduced a regular class feature of discussing controversial topics. The kids were older, and it wasn’t out of the question that they could now benefit from some classroom debate on current events. Fair enough.

But this is how the teacher handled it: She introduced a topic, told the kids what she thought was true, and then she asked them what they thought. So when the topic of the day was abortion, she announced that all religions were cults, and that the Catholic Church was sending protestors to shut down abortion clinics and that women would die because of it, and that she herself always donates to Planned Parenthood to save the lives of young women. Then she asked the class what they thought.

It is true that, technically, she was giving everyone an equal opportunity to make their views heard. But it is also true that every single kid in that room received the intended lesson: That abortion is good, and religious people, like my kid, are bad.

If this essay slips outside its normal bubble and you, dear reader, happen to agree that abortion is good and religious people are bad, then just swap in something you disagree with. Imagine she was teaching your kids that sandals are an affront to God and Pickleball causes impotence. Or imagine she is teaching your kids that most kids with gender dysphoria grow out of it (which is perfectly true, but it’s not what people want to hear right now!). I guarantee you, someone somewhere in the country is using taxpayer dollars to teach a roomful of children something that you think is reprehensible or ridiculous, and you would be pretty mad if the courts said you weren’t allowed to opt out.

But the point is, the teacher taught this lesson without using a single book. I suspect that, if I had requested a book list, I would have found nothing objectionable on it; and if I had asked for a curriculum description, it would have said “current events.” The only way I found out what was going on at all, was that my kid told me. And the only way the administration knew was because I told them!

As it happens, the next year, this same teacher committed a much graver offense, which was very clearly against written school policies. Again, my kids told me about it; my husband and I went to the school to complain; and the teacher was removed. I can’t help thinking that part of the reason the kids came to us was because we didn’t behave like maniacs last time they came to us. We tried our best to be reasonable. Kids want to be defended, but most of all they don’t want to be embarrassed.

So here is what I keep returning to. I do believe that parents have the right to know what their minor children are reading and learning and doing and saying in school. Of course they have that right! Parents are responsible for their own children, and it would be irresponsible for parents to send them off to school without knowing what they are going to be taught, just as it would be irresponsible to send them off on vacation with people they didn’t know, or off to explore in a country that wasn’t mapped.

Parents are responsible for their kids, and to be responsible, they must have information. It is insane to behave as if teachers by default have some sort of inherently superior wisdom and discretion, and parents by default have some inherently deficient ability to decide what their kids need.

Most teachers I have met do not want to take authority away from parents. They do not want to clash with parents, they do not want to have conflict with the community, and they have so many other fish to fry that the last thing they want is to see their names on the news.

But there are some teachers who do. And there are plenty of bad actors in the community and on social media who are more than willing to spread the word that any parent who protests is some kind of knuckle-dragging moron who thirsts after the death of the marginalised. Maybe they are; maybe they aren’t. Maybe they just want to see a book list.

Maybe they just want to know what it is their kids are doing all day. This is a reasonable desire. So yes, I believe that parents have the right to know what their minor kids are reading and hearing and watching at school.

I also believe that no amount of information can replace a trusting relationship between parent and child, where kids can ask questions without getting yelled at, and they can bring home concerns without worrying they’re going to be humiliated.

This is where the real work comes in. This is where impressionable children actually grow up into solid, caring, thoughtful, well-formed adults: When they know they’re allowed to talk about things with a trusted adult. Parents must try as hard as they can to be that person. If you build these relationships patiently and steadfastly, year by year, then you might possibly find yourself having the conversations that start, “Hey, we had a weird conversation in science today” or “Our health teacher said such-and-such; is that true?” or, heaven help us, “The kids on the playground were calling this one boy something that sounded mean, but I don’t know what it meant.”

So yes, I believe that the school should be communicating openly with the parents. But even more importantly, the parents should be making it possible and comfortable for their kids to be communicating openly with them. If I sent my kids to a school where they learned nothing but good, true, and beautiful things, but they didn’t feel that they could come home and talk to me about them, I would have failed.