This is the final instalment of my three-part series focusing on the Theological Reflection of the Plenary Council’s Instrumentum Laboris, with a special focus on the passages under the heading “the Joy of the Gospel”.

In my first column, I focused on what Pope Francis called the “New Pelagianism” and its resultant posture of frenetic activism, while my second column on the “New Gnosticism” obsessed over abstract belief and a disengaged quietism.

I wrote that these tendencies were the new faces of ancient heresies, which were at work in every Christian, including those who might be regarded as “good Christians”.

I wrote that so long as these tendencies persist, the striving for genuine renewal in the Church sought by the Plenary Council would end up instead regurgitating the same old things and putting them in shiny new packages.

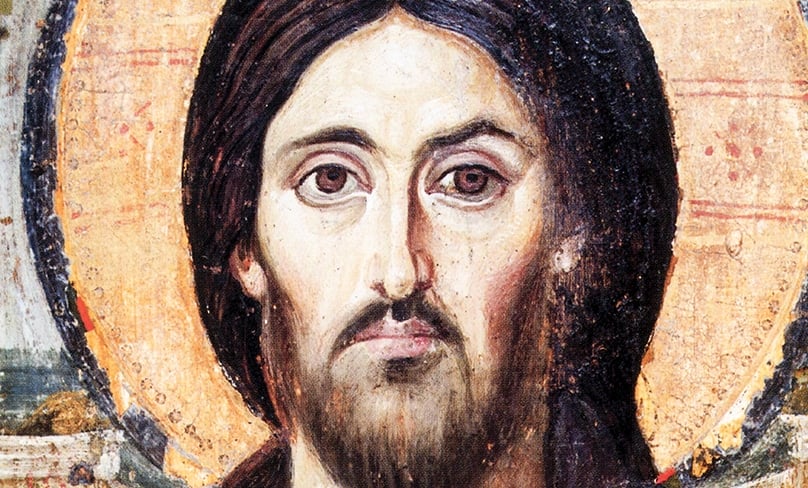

In this final piece, I wish to focus on a third ancient face, one whose presence reverberates through each paragraph in this section in varying and subtle ways which I want to make explicit. This is the ancient face of Christ.

“It seems to me that what the Instrumentum seeks to bring out in this segment is that this particular face – Jesus Christ’s face – is not a passing spectre, but an abiding gaze. “

The document rightly preferred the more theologically correct “incarnate” to denote this presence. Be that as it may, what risks getting lost in the dogmatic formula is the visceral experience that the dogma makes possible: a living, breathing and abiding encounter with God, who became a living breathing person with a face.

The segment’s use of the words “incarnate”, “encounter” and “presence” may be intended to denote something that can be experienced, yet even these could slide into the realm of abstractness.

However, a face denotes something different, for we cannot hold in our minds an abstract face (since an abstract face is no face at all). Instead, we need a particular face.

It seems to me that what the Instrumentum seeks to bring out in this segment is that this particular face – Jesus Christ’s face – is not a passing spectre, but an abiding gaze.

The Church Fathers assure us that the presence of Christ is everywhere. At the same time, this presence comes with a face that gazes at us in particular.

The particularity of Christ’s gaze accentuates the ongoing nature of His presence. As ages come and go, empires rise and fall and heresies take hold then fade away, and family, friends and situations may enter and exit our lives at a rapid pace.

Yet the face of Jesus Christ remains an anchor at every phase in our history. Fr Julian Carron, president of the ecclesial movement Communion and Liberation said that the gaze of Christ is so sure that “will never be uprooted from the face of the earth”.

As the face of Jesus endures on this earth, it would be a mistake to call this presence unchanging or static. This is because what endures is the presence of Christ, the Word of God who was present “in the beginning” and through whom all things had their beginning, as John’s Gospel tells us. We can draw from this passage an important and inseparable couplet; that of the presence of the Word and the beginning of all things.

What this means is that “the beginning” in John’s Gospel is not merely a past thing. Because the presence of the Word continues, so too does the beginning of all things. In the words of the philosopher John Milbank, so long as there is the face of Christ, there is “the uninterrupted flow of the one initial Creation”.

In short, reality in Christ is not static, for as St Paul writes in his Letter to the Romans “all of creation groans with the expectation of the revelation of the sons of God” (Rom 8:19) and with it, there is expectation of a new beginning, a new Genesis.

“This gaze is not abstract, for each and every one of us comes to this gaze in the Eucharist.”

This is why the Son of God, revealed within God’s Creation by becoming Man, can then say in the Book of Revelation “behold, I am making all things new” (21:5).

Thus, before any program or even before any dogmatic assertion, it is the anchoring in the gaze of Christ that ensures the genuine renewal the Church longs for.

This gaze is not abstract, for each and every one of us comes to this gaze in the Eucharist.

The practice of the Eucharist is not simply a real presence, but also a re-turning to the beginning when all our activism and retreat into theory has failed.

So long as the deliberations of the Plenary Council keep the Eucharistic Lord as its centre and horizon, it has the sure foundation for joining all of creation in its search for genuine renewal.

Related: