The release of the draft new syllabus in history for years 7-10 by the NSW Education Standards Authority raises old issues about the ideological direction of history in schools. The press release on the draft rightly emphasises a new compulsory module on “Aboriginal Peoples’ Experiences of Colonisation in Australia (c. 1700–1901).” The traditional narrative of nineteenth-century Australian history involving convicts, governors, squatters and Federation is relegated to an option (which mentions neither sheep nor gold).

The story of aboriginal experience of colonisation is a potentially interesting one, as two of the most different cultures on earth clashed and reached an accommodation. It is methodologically interesting too, as the evidence comes almost entirely from the white side so students have to stretch their historical imagination to understand what it must have been like from the indigenous perspective. But there are also temptations to fill the evidence gaps with ideology and to highlight atypical parts of the story.

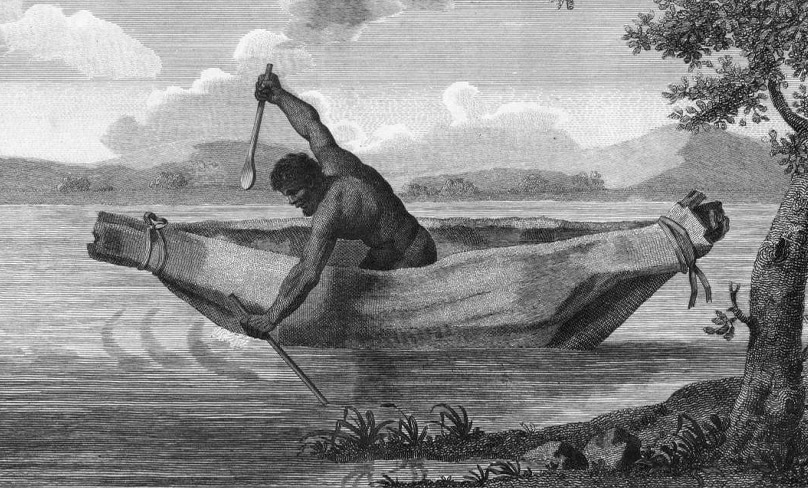

The basics of the story are clear: after initial restraint and mutual interest on both white and black sides during Governor Phillip’s time, a tragedy unfolded beyond the frontier as introduced diseases ravaged black populations. White immigrants and their animals then spread across the best countryside without regard to indigenous rights to land. Individual incidents of violence like the Appin Massacre of 1816 did not add up to Frontier Wars of the kind seen in the US and New Zealand, as the power differential made organised resistance obviously futile.

The power imbalance naturally led to widespread exploitation; as the first Archbishop of Sydney, John Bede Polding OSB said in 1869, “White men have too often been apostles of Satan.” Surviving black groups, mostly of mixed race, adjusted by creating a remarkable hybrid of very disparate cultures, taking advantage of white inventions like reliable food supply, clothing and shelter. They are the ancestors of the black communities of today.

That narrative, especially the cooperative parts, is largely invisible in the draft curriculum. The draft instead deals in the ideological imposition of the terms “Frontier Wars” and “resistance” (a word that occurs four times in the module outline). Men of extreme violence like Pemulwuy and Musquito are dubbed “resistance figures.” The story is not entirely one-sided, in that Bennelong, Patyegarang and Jacky Jacky are mentioned and presumably cannot be studied without mentioning their cooperative relationships with whites, although that is not mentioned. People later than the era of early contact do not rate mentions, such as Mary Ellen Cuper, the aboriginal telegraphist at New Norcia mission in 1874.

The draft’s simplistic narrative of white colonisation and black resistance has no sense of the perspectives of different actors: on the black side, “myalls” who avoided contact versus assimilators, men versus women, those who made first contact versus those born into a white-dominated society; on the white side, government, squatters, later settlers and missionaries.

There is some concern too over what students will have learned by the time they reach this module. Their brief study of the ancient and medieval world may not have included anything about the West. If teachers have chosen Ancient China or India, then for the Middle Ages the Angkor/Khmer Empire or the Mongol Expansion, students will have got to 1600 without hearing of the Greeks, Jews, or Europe—a compulsory “broad-brush” module on “the Ancient World” does not explicitly mention even Greece or Rome.

The period from 1600 to 1800, the foundation of the modern world, is called “The Era of Colonisation” (a compulsory 10 hours). The module deals with, for example, “Debates about the nature and significance of ethnocentric ‘discoveries’” but does not mention the Scientific Revolution. It provides the immediate lead-in to the 15-hour compulsory “Aboriginal Peoples’ Experiences of Colonisation in Australia”.

Commenting on the draft, UTS historian Anna Clark said that after the “heat of the history wars” in recent decades, the changes “represent a powerful inclusion about understanding Australian history and how it is taught it in schools.” Unfortunately, the draft document is itself a shot in the history wars and shows that they are far from over. The proposed syllabus deprives students of an adequate understanding of the European culture that Australia derives from, and replaces it with a crude vision of indigenous perspectives.

Interested parties can read the draft and provide feedback by visiting https://nswcurriculumreform.nesa.nsw.edu.au