A palliative doctor explores the lost art and wisdom of a gentle death for all of us

Any supporter of euthanasia can get any number of reasons why such activities are evil and contrary to humanity on numerous levels (socially, economically, psychologically). No one has hidden these arguments from the general populace.

Just the opposite, these arguments are easily found with a quick internet search. However, the arguments alone aren’t enough. If they were as good as the interlocutors proposed, legalising euthanasia would not happen. Arguments might change minds, but they don’t change hearts.

In other words, if you want to change hearts, the language of the heart is needed. The heart’s language is none other than a narrative story. Stories have a way to enter hearts by engaging imagination while sidestepping reason and rationality – almost like a backdoor into the mind – the narrative presents food for thought for the mind.

Narratives function by allowing the audience to participate and experience, even if only vicariously, the story and feelings of another. For instance, there is no rational reason for men to cry over Captain America wielding a Norse god- turned-comic-book-superhero’s mythological weapon. Yet, this is what happened in The Avengers: End Game.Stories have the power to move hearts and eventually change minds.

Therefore, if people want to get serious about ending euthanasia, and abortion for that matter, the narrative must change. Whoever controls the narrative, controls the direction the culture takes.

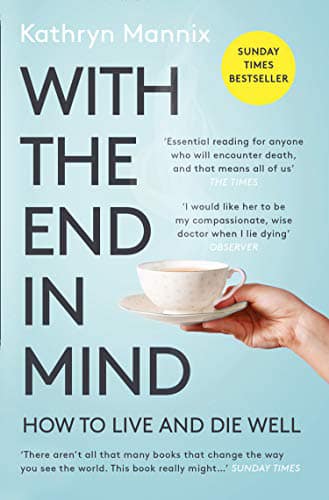

Enter palliative physician Kathryn Mannix’s book With the End in Mind: Dying, Death & Wisdom in an Age of Denial.

In her book, Mannix seeks to put societies, particularly Western societies, back in touch with the dying process. She argues that humanity was intimately familiar with death before the medical advances during the mid-twentieth century.

Today, death is the domain of technocratic medical institutions where the dying are removed from society and away from family. She mended this broken link by placing the narratives of dying people, real-life events and true stories front and centre of the book.

She does this by showing how death is, first, a process and that even though it is emotional, it need not be empty; it need not be painful; it need not be chaotic.

In other words, death does not have to be the way euthanasia supporters say death will be. Difficult conversations become comforting encounters through information and knowledge of the dying process.

There is Alex, a young man with testicular cancer who finds special connections through humour with the other men in a room on the oncology ward dubbed, the Lonely Ballroom.

Eric, the former head of school who wanted to end his life before his grandchildren see him waste away found, through his family and doctors, solace and dignity.

In the end, Eric didn’t say “yes” to dying, but “yes” to living, and was glad he was alive for one more family Christmas. The teenage girl musician, facing her second round of leukemia who makes a “project,”a memory pillow quilted out of bits of her favourite and most meaningful clothes for her mother.

The author divides her book into six sections. Patterns tell the story of people who learn about the process of dying. My Way articulates the usefulness of denial, acceptance, and cognitive behaviour therapy and how people cope with the dying process. Naming Death seeks to strip away the metaphors and euphemisms of death to reclaim the language of death and dying to reduce the superstition and fear associated with dying.

Looking Beyond the Now examines how assumptions and reinterpretations of situations give new insight into life and the dying process. Legacy explores how patients seek ways to be remembered either by their family or community after they die.

Transcendence tells the story of patients who have a spiritual reckoning, so to speak, that is meaning beyond themselves, in how they respond to the world around them as their true character and humanity is shown in dying.

The one fair criticism is that not every death is or can be as peaceful as the doctor describes. However, she argues in narrative stories that palliative care teams can, with the proper treatment, make the dying process as peaceful and as pain free as possible while maintaining the dignity of the patient until his or her death.

Mannix writes in the introduction, “The death rate remains 100 per cent, and the pattern of the final days, and the way we actually die, are unchanged.” She also writes, “The art of dying has become a forgotten wisdom but every deathbed is an opportunity to restore that wisdom to those who will live, to benefit from it as they face other deaths in the future, including their own.”

Take warning: this is the only book I have ever read to have a health warning included: “Health warning: these stories will probably make you think not just about the people in them, but about yourself, your life, your loved ones and your losses. You are likely to be made sad, although the aim is to give you information and food for thought.”

These stories will move and maybe make readers feel a little uncomfortable and tearful.If you cry easily, keep a box of tissues within arm’s reach.

The poet Dylan Thomas famously wrote, “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Mannix might reply, that that good night is gentle and that is the way death can be.

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial (Paperback). Published by HarperCollins GB. Paperback, 359 pages.

Related Articles:

Paul Catalanotto: You may not be evil, but don’t get ahead of yourself