“High Court rules sperm donor is legal father,” read the headlines last week. No matter which outlet you looked at, the description of the “landmark” case was the same.

The decision was significant, of course. Most High Court rulings are. But the significance of the decision was not that it ruled sperm donors are fathers (it didn’t), but rather that it seems to have left the door open for allowing a child to have three legal parents.

Just a quick summary of the case: Susan Parsons and Robert Masson (not their real names) had been friends for a long time.

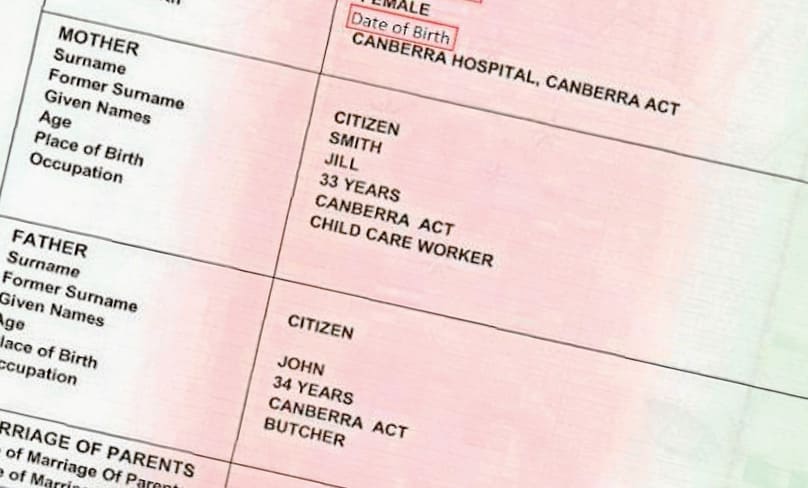

In 2006, Masson provided his sperm to Parsons so that she could fall pregnant, on the understanding that he would support and care for the child, even though the child would live with Parsons and her female partner. Masson was named as the father on the birth certificate of their daughter and she calls him “daddy.”

He has always had an “extremely close and secure” relationship” with her, and financially supports her as well.

Parsons has a second child who is not the biological child of Masson. She and her partner sought to move with the children to New Zealand in 2015, but Masson objected. This was the catalyst for the legal proceedings.

In their decision, the High Court judges waded through the different state and federal legislative provisions that pertain to parentage, but it all looked a bit messy when applied to this particular set of facts.

For example, the federal law, the Family Law Act says that if a child is born via artificial conception and the birth mother was married or in a de facto relationship at the time, then her partner is presumed to be the child’s other parent. It also specifically says that in these circumstances, anyone else who provides “biological material” is not a parent.

This provision did not apply to this particular case because the two women were not in a de facto relationship at the time of conception.

The Family Law Act also says that a person who is registered on the birth certificate as a parent is presumed to be so. In this case, Masson was listed as the “father” on the birth certificate, so he is presumed to be just that.

The NSW law is slightly different. The Status of Children Act says similar things about birth certificates and artificial conception, but also includes an irrebuttable presumption that if a woman uses an artificial conception procedure and the sperm is provided by a man who is not her husband, then he is not the father.

An “irrebuttable presumption” is one that cannot be changed by evidence or circumstances. Under NSW law, Masson was not and could not be the father of the child.

Faced with the inconsistency between the two pieces of legislation, the High Court applied the federal law and declared Masson to be the child’s legal father.

The High Court did not say that all sperm donors are fathers and specifically declined to comment on that question given that it was not relevant in this case. Masson is and was much more than a sperm donor.

The decision might have been different had Masson not been on the birth certificate or had little contact with her throughout her years. It most certainly would have been a different outcome if the two women had been married at the time of conception.

What is much more interesting – and alarming – than the sperm donor stuff is that the Court said the Family Law Act provides an expansive definition of who could be a parent.

The Court held that the effect of the relevant provisions of the Family Law Act “is plainly enough to expand rather than restrict the categories of people who may qualify as a parent of a child born as a result of an artificial conception procedure.”

The judges went on to cite with approval an English case where it was said there are “at least three ways in which a person may be or become a natural parent of a child,” that is, genetically, gestationally and psychologically.

In this case, it seems, Parsons was genetically, gestationally and psychologically a parent. Masson was genetically and psychologically so, and Parsons’ partner just psychologically.

But if there are “at least three ways” to be a natural parent, then does it not follow that there are “at least three” natural parents?

It is a bizarre twist of biology: the idea that there are at least three ways to become the natural parent of a child seems rather unnatural to me.

But that is where we seem to be headed in a society that normalises same-sex marriage and artificial conception, with or without donor gametes. In certain parts of Canada now, a child can have up to four legal parents registered on their birth certificate.

What this has meant is that a birth certificate is no longer a document recording a birth, but primarily a document recording the social relationship of the adults responsible for the child’s conception and/or care. Because it’s all about the child, except for the bit that’s about the parents.

Australia is not far behind Canada on this score. Last week’s headlines were right to call the decision a “landmark” one; they just missed the reason why.