Catholic Theology is the latest in Bloomsbury’s series that introduces the theological traditions of the major Christian churches – Anglican, Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, Reformed and, now, Catholic – to those who want to learn more about their own faith, those wanting to understand better the rival but complementary theological traditions of fellow Christians, and those who are simply curious. Each volume examines the ‘foundations, key concepts, eminent thinkers, and historical development’ [Frontispiece] of a particular tradition and I’m happy to say that Professor Rowland’s satnav for finding our way around Catholic theology is very successful indeed. Tonight I’d like to ponder why we might need such help and identify four particular respects in which this book answers our need.

Why we need Catholic Theology

Tolkien’s Silmarillion opens with the God Eru singing the world of the spirits into existence and giving each a theme with which to make great music. But Melkor, the most powerful spirit, wants to call his own tune and so repeatedly intrudes discordant notes into the cosmic symphony. Some of the demiurges join him. How is Eru to respond? Should he stop the orchestra, stop sustaining the universe? No, his response to this rebellion is, time and again, to introduce a new theme that cleverly takes up the daemonic noise, as well as the good spirits’ melodies, into his symphony making it even more beautiful than before. Next, through waves of natural destruction, Melkor and his devils set themselves to mess up the material world being prepared for elves and men.

But by Eru’s wise design, this too only contributes to the ultimate beauty of things: without a volcano like Mount Doom there would never be the fertile valleys of the Shire. Against this visible and invisible backdrop the epic human struggle between good and evil would play out in Tolkien’s subsequent novels.

Before dismissing such fantastical legends as the stuff of fantasy novels and films, not real life, we might recall that J.R.R. Tolkien, like Dr Rowland, was first and foremost an on-the-knees praying Catholic. He knew that God the Father does indeed eternally sing the Word who is His Son and that the mutual love between them is the Holy Spirit. That divine music keeps playing itself out, in creation itself and in re-creating human beings for greatness. It makes them images of God (Gen 1:26) – free, rational, loving beings destined for eternity. It takes up every human achievement and mistake, as well as every non-human good and evil, conducting, correcting, harmonising and redeeming all until eventually all creation will be one great symphony of love and life, beauty and goodness. In the meantime, there are some sour notes that reduce human beings from images of God to mere producers of commodities and consumers of pleasure; that proclaim sex, money, power and technology are what most matter; that turn partial and ideological conceptions of reality into whole interpretive keys. Catholic hymns are different.

In treating the marks of a true and false pluralism in Catholic theology – or to use the language of Joseph Ratzinger a ‘fruitful’ and a ‘disintegrative’ pluralism (p.16) – Rowland notices the 1990 CDF Instruction on the Ecclesial Vocation of the Theologian which speaks of two dynamisms of theology: the dynamism towards truth and the dynamism towards love. Perhaps with the Silmarillion in mind the Instruction concludes that “The truth of the faith resonates not as a mono-phony but as a sym-phony… composed of the many apparently quite discordant strains in the contrapuntal interplay of law, prophets, Gospels and apostles. The omission of one of the thematic elements of this symphony simplifies the performance but is rejected by the Fathers as heresy, that is, as a reductive selection, because the truth lies only in the whole and its tensions.” (p.17)

Theological taxonomy

Rather than using the analogy of the symphony, Pope Francis once likened humanity to a polyhedron; unlike a perfect sphere, which is simple, smooth, equal, and each part indiscernible from the next, a polyhedron, which may look like a sphere, is multifaceted, each part distinguishable from the next but united as a whole. Humanity, Pope Francis explained, is like such ‘a polyhedron in which the multiple forms, in expressing themselves, constitute the plural elements that compose the one human family.’

In using this analogy we might wonder if the Pope was preferring a geometric analogy to the musical one used by Tolkien and Ratzinger. But I think it more likely that he was preferring a sporting metaphor to both the geometric and the musical: the image in his mind was probably his beloved soccer-ball which, though apparently spherical, normally consists of twelve pentagonal and twenty hexagonal panels positioned in a truncated icosahedron – as the notoriously sporty Tracey Rowland would no doubt explain.

Something similar might be said about the Church: this two-thousand-year-old slice of redeemed and redeeming humanity has many histories, cultures, languages, epistemologies, moralities, aesthetics and temperaments; by common faith and practice, it draws together that extraordinary diversity of humanity into one church – a Church much flatter and more decentralised in its organisation, a Church much less directive in its pastoral governance and intellectual reflection, a Church much less consistent ideologically and behaviourally in its membership, than many presume or desire. And if such can be said about humanity in general and Catholic humanity in particular, the same is surely true of Catholic theology. How is the millennial generation of Catholic scholars and curious onlookers to make sense of what Professor Rowland calls the theological ‘zoo’ (p.207) – a rather open plan, open plain zoo at that?

The first theologians – those to speak to God and about God – were of course Adam and Eve, and the first task they were given was to name the world around them. Even before he was a gardener, or perhaps because he was a gardener, Adam was a taxonomist – someone devoted to identifying, classifying and describing the things around him, especially the living things: people, animals and plants. And this is the greatest strength of Dr Rowland’s work: she identifies, classifies and describes for us the various competing if also complementary strands of Catholic theology today.

And so after her introduction and consideration of ‘Fundamental Issues and Building Blocks’ [Ch. 1] of Catholic Theology, our author turns to the ‘Hallmarks and Species’ of four Catholic theological phyla: Thomism – to which one might have added: ‘and the Papacy of John Paul II’ [Ch. 2]; ‘The Communio Approach’ – to which we might pair: ‘and the Papacy of Benedict XVI’ [Ch. 3]; ‘The Concilium Alternative’ – to which we might add: ‘and the Papacy of the Theologians’ [Ch. 4]; and, finally, ‘Liberation Theology’ which our book has already paired with: ‘and the Papacy of Francis’ [Ch. 5].

In the course of these chapters Tracey Rowland ranges from the Scriptures, Fathers, Scholastics and recent Magisterium, to these four principal contenders for the soul of Catholic theology in post-modernity.

Along the way we meet the recent popes and their close advisers, the great names of Catholic theology such as Rahner, de Lubac, von Balthasar, Schillebeeckx, Ratzinger, Grisez, Kasper, Scola and Gutiérrez, their philosophical companions such as Descartes, Kant, Marx, Freud, Heidegger, Maritain, MacIntyre and Tolkien, and a number of younger up-and-coming contributors. Professor Rowland also had the wisdom to refer to around twenty-five Dominicans, so she and we must have been doing something right!

Theological genealogy

In identifying by name, classifying by distinctive features, and describing by their qualities the different species, taxonomists are often genealogists as well, and Dr Rowland is a theological genealogist as much as taxonomist. By helping us to understand the ‘genetics’ of particular ideas, their intellectual great-great-grandparents and intervening ancestors, as well as the environments in which each was tested and thrived, she enables us to be not merely tourists at the theological zoo, saying hurray or boo to particular animals, but informed, appreciative viewers who understand something of where each creature has come from and what it is that is so special about it.

No faith tradition has come near Christianity – and especially Catholic Christianity – for sheer quantity of theologians, philosophers and those in allied disciplines, often employed by universities, institutes and theologates, engaging in rich and ongoing debates about many aspects of Christian faith and practice, engaging with the other academic disciplines and signs of the times, and publishing an enormous quantity and variety of serious academic research as well as more popular writing. Sociologists and historians of religion offer complex reasons for the theological fruitfulness of Christianity, but at its heart are the matters identified in Pope Benedict’s famous Regensburg Address: the regard our particular mind-body anthropology, our Logos-Incarnational Christology, and our Trinitarian-modelled community all have for intellectual curiosity, discovery, articulation and development. Such a faith could never be content with a single and simplified conception of reality, with merely repeating a few slogans and obeying a few commands, and with imposing this on every culture and individual it encountered.

Theological diagnosis

Of course, while variety may be the spice of life, not everything is a spice: no arsenic on the canapés please! Not every melody will contribute to the cosmic Symphony, at least without an Eru constantly intervening; not every surface will contribute to the polyhedron being the right shape to play soccer with.

In her introduction Dr Rowland quotes the American writer Anthony Esolen who compares the Catholic Church in the first decades of the 21st century to a sleeping dragon, snoring on top of his horde of gold [p.5]. Once again one glimpses Tolkien – in this case The Hobbit – in the background. In what plays out in Rowland’s subsequent chapters we come to appreciate not only the individuality, genealogy and beauty of each species of Catholic thought, but also the dysfunctionality of much that goes by the name of contemporary culture, academic discourse and even Catholic theology. Too often complexity is reduced to system or slogan at the expense of beauty and truth, Revelation and tradition are de-constructed and re-constructed to suit personal or political interests rather than reverently and gratefully received as a gift by which to critique those interests, harmony is lost in ‘disintegrative pluralism’, and culture and history are debased or faith kidnapped by narrow conceptions of secularity, enculturation or practicality. The dysfunction that follows in individual lives, families, institutions and whole societies is increasingly obvious, but Dr Rowland’s book gives us some keys to understanding just what has gone wrong and why.

One of the tensions that plays out in the debates between the Communio and Concilium schools through which Rowland guides us is that between logos and ethos, theoria and praxis.

In her final chapter the author elegantly demonstrates how those amicable both to Concilium theologies and to Marxist, feminist or ecologist sociologies developed ‘liberation theologies’, which prioritised praxis over faith [p.173].

Yet faith’s authentic praxis surely depends on faith’s authentic truth revealed in Christ and appropriated in the sacrament of the Church. Disconnected from the truth of faith, praxis and relativises all belief and loses its anchor in the verbum rememorativum, the verbum demonstrativum and the verbum prognosticum [cf. p.21] Thus the liberation theologian, Leonardo Boff, could conclude that:

The actual content of Christ or Buddha refers to the same reality. Both reveal God. Siddhartha Guatama is a manifestation of the cosmic Christ in the same way as Jesus of Nazareth. Or Jesus of Nazareth is an Enlightened One, like Buddha. [p.176]

Understandably, this view did not win Boff many friends at the CDF.

Rowland quotes from Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy to the effect that:

The Church forgives everything more readily than an attack on truth. She knows that if a man falls, but leaves truth unimpaired, he will find his way back again. But if he attacks the vital principle, then the sacred order of life is demolished… Any attempt to base the truth of a dogma merely on its practical value is essentially uncatholic… The will must [have the humility to] admit that it is blind and needs the light, the leadership and the organising formative power of truth. It must admit as a fundamental principle the primacy of knowledge over the will, of the Logos over the Ethos. [p.133]

Yet typically of the Catholic ‘both-and’ which Tracey Rowland demonstrates for us time and again, she then shows us how praxis theologies have often been useful correctives to spiritualities that emphasise God’s transcendence to the neglect of His immanence, and so neglect the love of neighbour in a vain pursuit of the love of God.

Theological therapy

In numerous ways Professor Rowland demonstrates her conclusion that:

Some Catholic Scottish crofters, including a few Orcadian fishermen, may in fact have a deeper understanding of the Catholic faith and a closer relationship to the Trinity than someone with a degree from the theology faculty of the University of Leuven, but not because they are poorer than middle-class professionals at Europe’s elite universities. The Catholic world view is sufficiently rich to affirm the works of the saintly scholars as well as the saintly fishermen, farmers, labourers, lawyers and so on. In the architectonic world of a Catholic culture, each has a place, and each social and vocational group has its particular responsibilities, and even particular patron saints. [p.203]

Professor Ramsay will be pleased to hear that there is hope of salvation even for Scottish academics as there is for Scottish fishermen!

So what must we do? What is the theological therapy Rowland offers – the Catholic traditions offer – for the distempers of modernity? In her first chapter our author identifies some fundamentals of anything deserving the name ‘Catholic theology’. Her subsequent chapters illustrate how these play out in different theological taxa.

They also point the way forward if the sleeping dragon of the Catholic academy is to wake up and share its store of gold with the Church and the world. We must recover a deep reverence for the mysteries of God, the world and ourselves, and re-nurture the relationships between system and mysticism, dogma and history. We must re-appreciate the unity-dualities of the Old and New Testaments, of faith and reason, of doctrine and history, of religion and culture, of faith and praxis. Amongst the distinctive family traits of good Catholic theology will be an orientation to the theological ‘both-and’ more often than the ‘either-or’; a focus on Trinity and Incarnation, on Jesus and Mary, on nature and grace, on logos and ethos; and a particular take on the relationships between Scripture and tradition, between historical-critical method and theological exegesis, and between Magisterium and theologians.

To have an eye to so many different things is difficult for anyone. To show how these different elements combine into that creature or creatures we call ‘Catholic theology’, in a way that is engaging and accessible, and to do so in a mere 267 pages, is a genuinely impressive achievement. For this we should all be truly grateful to Tracey Rowland, and proud of her as our academic colleague in the University of Notre Dame Australia and as our fellow-Australian making such a mark in the international theological scene and especially in the International Theological Commission of the Vatican. If you want not just a guide to the taxonomy and genealogy of the Catholic theological zoo, but also a way to understand the crises of Church and society and the therapies that might be offered, I strongly recommend to you Catholic Theology by Tracey Rowland.

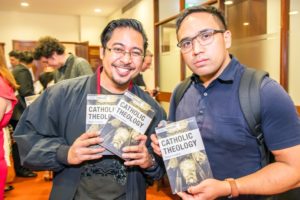

This is the edited text of the address by Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP at the book launch of Catholic Theology by Prof. Tracey Rowland — available in hard copy or as an ebook — at the Broadway Campus (Sydney) of the University of Notre Dame Australia on 13 March 2017. Hyperlinks have been added by The Catholic Weekly and do not necessarily reflect the views of Archbishop Fisher.