COMMENTARY

AT THE NAME OF JESUS

In the mid-1970s a good number of Jesuit colleges, universities, and high schools in the United States came up with a new brand. The goal of a Jesuit education, they proclaimed, was to educate “men for others” – which quickly morphed, of course, into “men and women for others.” The slogan derived not from some high-powered Madison Avenue advertising agency. It was the genial intuition, or so it was claimed, of the man who was then the General of the Society of Jesus, Father Pedro Arrupe.

Concerned about what seemed to me a severely reductionist understanding of the mission of a Catholic high school or college, I sought to trace down the original context of that rotely repeated phrase. It stems from a 1973 address that Father Arrupe gave to European alumni of Jesuit schools and colleges.

Arrupe indeed employs the telltale phrase several times in his address, whose focus was “education for justice.” But what I found revelatory was that Arrupe himself gave a far richer and more distinctively Christian thrust to his proposal. Thus in his first setting forth of the theme he makes this explicit avowal: “Today our prime educational objective must be to form men-for-others; men who will live not for themselves but for God and his Christ—for the God-man who lived and died for all the world.”

And, in the concluding section of his address, Arrupe further elaborated the Christological foundation of his proposal. A man for others “is the man filled with the Spirit; and we know whose Spirit that is: the Spirit of Christ, who gave his life for the salvation of the world; the God who, by becoming Man, became, beyond all others, a Man-for-others.”

It would be an interesting exercise to consider why the Christological substance was so evidently eviscerated from the subsequent sloganeering. A desire not to appear “parochial?” Not to offend “secular sensibilities?” To manifest greater “ecumenical sensitivity?” As an alumnus of a Jesuit high school, college, and university, I have over the years sought to prod some of my Jesuit friends to espouse and articulate the full-bodied Christic vision not only of Father Arrupe, but even more authoritatively of the Second Vatican Council whose documents, I have argued, are Christologically saturated.

But such a recognition and acknowledgement is also incumbent upon some sectors of the American Catholic theological guild as well. I have witnessed over the years that Catholic theology in the United States is often marked by what one perceptive friend calls a notable “Christological deficit.” This is not the occasion to expound the case at length, but as a not uncommon instance, let me refer to a recent article in Commonweal.

The article, entitled “The Changing Role of Catholic Moral Theologians,” is a report on a recent global conference of participants in the project, Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church. The article offers a quick overview of developments in Catholic moral theology since Vatican II, both in its approaches and in its practitioners. And it celebrates the current rich (sometimes bordering upon promiscuous) pluralism.

To her credit the author, M. Cathleen Kaveny of Boston College, did raise a concern about “how our field will organize and prioritize these diverse methods, perspectives and questions so that they do not devolve into a cacophony.”

Upon reflection, she came to the conviction that “three commitments” manifested themselves in the otherwise diverse presentations and approaches at the conference. One might call them three guiding theological “principles” (my term, not hers). She enumerates them as: 1) the goodness of God’s creation and human responsibility for its care; 2) the dignity of all, especially the poor and marginalized; and 3) the demands of human solidarity across diverse communities. Certainly these are foundational and exemplary theological principles and commitments.

But one cannot help but be struck by what is glaringly absent: THE Name is missing. In this, Kaveny’s piece mirrors the “Christological deficit” I and others have often discerned in certain circles within American Catholic theology. A Christological deficit, some have maintained, also mars the Synod’s working document, the Instrumentum Laboris. Foremost among these critics has been Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia. In an early intervention at the Synod, Chaput lamented: “If we lack the confidence to preach Jesus Christ without hesitation or excuses to every generation, especially to the young, then the Church is just another purveyor of ethical pieties the world doesn’t need.”

One prays that this Christological deficiency will be addressed and countered through a wise discernment of the Synod fathers that would give rise to a robustly Christocentric final document. Robustly and substantively Christocentric: not a mere pious and superficial invocation of the name of Jesus, but a careful exposition and proclamation of the uniqueness of the person of the Savior and the transformative call to discipleship Jesus issues. A document that echoes the Petrine witness: “For there is no other Name under heaven, given among men, by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:10–12).

As stimulus for their discernment over the next two weeks, the Synod fathers could hardly do better than to ponder carefully Pope Francis’ rich homily on the occasion of the canonization of the new saints this past Sunday, October 14. Francis told the thousands gathered in St. Peter’s Square: “Jesus is radical. He gives all and he asks all: he gives a love that is total and asks for an undivided heart. Even today he gives himself to us as the living bread; can we give him crumbs in exchange?” And the Successor of Peter then underscores the “today,” the perennial spiritual aggiornamento to which we are all called: “Today Jesus invites us to return to the source of joy, which is the encounter with him, the courageous choice to risk everything to follow him, the satisfaction of leaving something behind in order to embrace his way. The saints have travelled this path.” What more joyful and meaningful challenge to today’s youth (and to each of us).

For the saints canonized Sunday (and all the saints of the Church), Jesus is not some pious way-station, extracurricular to being men and women for others. Jesus is the curriculum itself, both the way and the goal of their faith journey: the Measure of their transformation.

I have long wondered whether the “Christological deficit” I have noted is the fruit of a Christological amnesia that stirring proclamation and catechesis might remedy? Or whether the malady runs deeper? Whether the symptoms point to a “Christophobia” – not on the part of opponents of Christianity, but, sadly and more troubling, by its “adherents.” A fear, as the poet Francis Thompson put it: “Lest having Him I must have naught beside.”

Such seems to have been the affliction of the “rich young man” of the gospel upon which the Pope preached. And a “field hospital” hardly seems an adequate setting to treat so debilitating a fear, so pervasive a phobia. It requires, rather, the sort of intensive care that issues in the radical cure of heart and mind that the New Testament calls “metanoia!” And this only the divine Physician can effect.

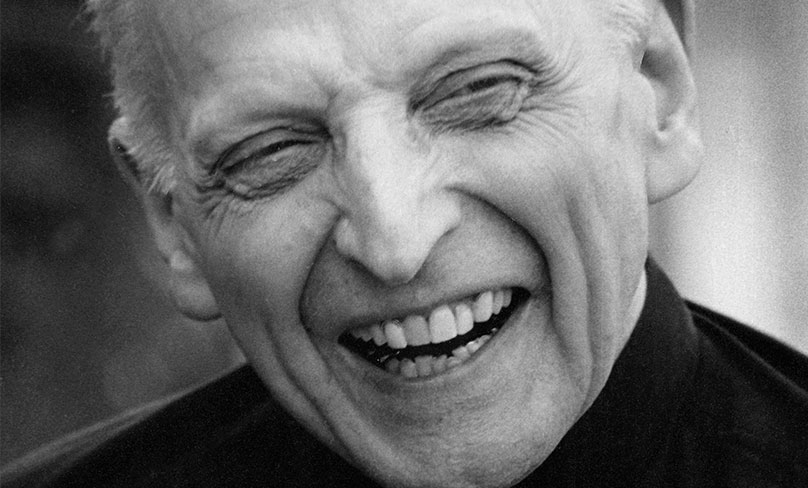

– Robert Imbelli

[Father Imbelli, a priest of the Archdiocese of New York who taught for many years at Boston College, is the author of Rekindling the Christic Imagination.]

JOHN PAUL II, YOUTH MINISTER

Pole that he was, Karol Wojtyla had a well-developed sense of historical irony. So from his present position in the Communion of Saints, he might be struck by the ironic fact that the Synod on “Youth, Faith, and Vocational Discernment” currently underway in Rome, coincides with the fortieth anniversary of his election as Pope John Paul II on October 16, 1978. What’s the irony? The irony is that the most successful papal youth minister in modern history, and perhaps all history, was largely ignored in Synod-2018’s working document. And the Synod leadership under Cardinal Lorenzo Baldisseri seems strangely reluctant to invoke either his teaching or his example.

But let’s get beyond irony. What are some lessons the Synod might draw from John Paul II, pied piper of the young, on this ruby anniversary of his election?

1. The big questions remain the same.

Several bishops at Synod-2018 have remarked that today’s young people are living in a completely different world than when the bishops in question grew up. There’s obviously an element of truth here, but there’s also a confusion between ephemera and the permanent things.

When Cardinal Adam Sapieha assigned young Father Wojtyla to St. Florian’s parish in 1948, in order to start a ministry to the university students who lived nearby, things in Cracow were certainly different than they were when Wojtyla was a student at the Jagiellonian University in 1938-39. In 1948, Poland was in the deep freeze of Stalinism and organized Catholic youth work was banned. The freewheeling social and cultural life in which Wojtyla had reveled before the Nazis shut down the Jagiellonian was no more, and atheistic propaganda was on tap in many classrooms. But Wojtyla knew that the Big Questions that engage young adults – What’s my purpose in life? How do I form lasting friendships? What is noble and what is base? How do I navigate the rocks and shoals of life without making fatal compromises? What makes for true happiness? – are always the same. They always have been, and they always will be.

To tell today’s young adults that they’re completely different is pandering, and it’s a form of disrespect. To help maturing adults ask the big questions and wrestle with the permanent things is to pay them the compliment of taking them seriously. Wojtyla knew that, and so should the bishops of Synod-2018.

2. Walking with young adults should lead somewhere.

Some of the Wojtyla kids from that university ministry at St. Florian’s have become friends of mine, and when I ask them what he was like as a companion, spiritual director, and confessor, they always stress two points: masterful listening that led to penetrating conversations, and an insistence on personal responsibility. As one of them once put it to me, “We’d talk for hours and he’d shed light on a question, but I never heard him say ‘You should do this.’ What he’d always say was, ‘You must choose’.” For Karol Wojtyla, youth minister, gently but persistently compelling serious moral decisions was the real meaning of accompaniment (a Synod-2018 buzzword).

3. Heroism is never out of fashion.

When, as pope, John Paul II proposed launching what became World Youth Day, most of the Roman Curia thought he had taken leave of his senses: young adults in the late-twentieth century just weren’t interested in an international festival involving catechesis, the Way of the Cross, Confession, and the Eucharist. John Paul, by contrast, understood that the adventure of leading a life of heroic virtue was just as compelling in late modernity as it had been in his day, and he had confidence that future leaders of the third millennium of Christian history would answer that call to adventure.

That didn’t mean they’d be perfect. But as he said to young people on so many occasions, “Never, ever settle for anything less than the spiritual and moral grandeur that God’s grace makes possible in your life. You’ll fail; we all do. But don’t lower the bar of expectation. Get up, dust yourself off, seek reconciliation. But never, ever settle for anything less than the heroism for which you were born.”

That challenge – that confidence that young adults really yearn to live with an undivided heart – began a renaissance in young adult and campus ministry in the living parts of the world Church. Synod-2018 should ponder that very, very seriously.

– George Weigel

[Reprinted with permission from Mr. Weigel’s weekly column, “The Catholic Difference,” October 17, 2018.]

TESTIMONY FOR THE SYNOD

As with most Catholic contentions over the past half-century, many of the arguments at Synod-2018 are expressions of different interpretations of What the Second Vatican Council Did. Does, for example, the Council warrant a re-reading or, or even a break with, the Church’s classic understanding of the human person and human relationships, especially in terms of human sexuality?

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD asked Dr. Eduardo Echeverria, Professor of Philosophy and Systematic Theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, for some thoughts on this ongoing debate. Dr. Echeverria’s essay follows. XR II

HISTORY, UNCHANGING TRUTH, AND VATICAN II

One of the most contentious questions in the reception of the documents of the Second Vatican Council involves the relationship between unchangeable and absolute truth, on the one hand, and the human expression of that truth in a variety of historically-conditioned forms of thought, on the other. In short: Given that they did not fall from heaven, how do we maintain the enduring validity of the statements of truth asserted in confessions, creeds, and dogmas, and, yes, the documents of Vatican II, while acknowledging their historical conditioning? The answers given to this question of unchanging truth and history reflect conflicting interpretations of Vatican II and its work-product, its sixteen documents.

Pope Benedict XVI identified two basic ways of interpreting the Vatican II documents: a difference that is at the root of the conflict over Vatican II itself and its meaning for the present.

Are the Council’s documents justifiably interpreted as being in discontinuity and rupture with the Church’s living Tradition? (Ironically, Neo-Modernists and Neo-Traditionalists both agree with this way of reading the documents; the former are “boosters” and the latter “knockers” of Vatican II.) Alternatively, should these documents be interpreted in continuity with truths long asserted by the Church (even as we recognize that the Council was engaged in a creative retrieval of the authoritative sources of faith – Scripture and Tradition – so that Catholicism might move forward faithfully into the future, itself renewed so that it could convert the world as it is today)?

This distinction between these two ways of reading Vatican II’s documents is not a magician’s wand capable of answering every burning question about the proper interpretation of the Council. But perhaps the answer comes from within Vatican II itself. I would argue that the Council’s own framework of interpretation – its own approach to the question of truth and history – was inspired by the such nouveaux théologiens as Yves Congar (1904-1995), Henri de Lubac (1896-1991), which seems to have been recognized by John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Congar, de Lubac, John Paul II (the pope who created both men cardinals), and Benedict XVI represent a creative retrieval of the authoritative sources, of reform and renewal in continuity with the Church’s living Tradition.

In this connection, it’s worth noting that Pope John XXIII invoked the distinction between truth and its historically conditioned formulations in his opening address at Vatican II, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia [Mother Church Rejoices]. That address has been read by many as a clear indication that the Pope wanted the considerations begun by the nouveaux théologiens to be given continued study. As he said in Gaudet Mater Ecclesia, “What is needed is that this certain and unchangeable doctrine, to which loyal submission is due, be investigated and presented in the way demanded by our times. For the deposit of faith, the truths contained in our sacred teaching, are one thing, while the mode in which they are expressed, but with the same meaning and the same judgment [“eodem sensu eademque sententia”], is another thing.”

The subordinate clause I’ve cited in its Latin original is part of a larger passage from Vatican I’s dogmatic constitution on faith and reason, Dei Filius, which is also cited by Leo XIII in his 1899 Encyclical, Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae; and this formula is itself taken from the Commonitórium Primum 23 of Vincent of Lérins: “Therefore, let there be growth and abundant progress in understanding, knowledge, and wisdom, in each and all, in individuals and in the whole Church, at all times and in the progress of ages, but only within the proper limits, i.e., within the same dogma, the same meaning, the same judgment” (in eodem scilicet dogmate, eodem sensu eademque sententia).

According to this “Lerinian” interpretation of dogma (and of Vatican II), linguistic formulations or expressions of truth can vary in our attempt to deepen our understanding, as long as they maintain the same meaning and mediate the same judgment of truth.

The documents of Vatican II are, however, interpreted in another way by those I’ll call Neo-Traditionalists. The Neo-Traditionalists are anti-Modernists, not only in their response to Modernism’s proposals, but because they don’t acknowledge that theological Modernism had actually identified a real problem in upholding the permanence of meaning and truth.

So the Neo-Traditionalists absolutize continuity of dogmatic truth without displaying any appreciation for the historical nature of the human expression of those truths.

Now the contention of the nouveaux théologiens, and arguably, of John XXIII and of the Council, is that, despite the untenable solutions of the Modernists, Modernism was on to something of importance for the future of the Church. As the Dominican theologian Aidan Nichols put it succinctly, “though Modernism had been a false answer, it had set a real question:” and the question is about the relationship between abiding, permanent truth and its historically conditioned formulation. The false answer of Modernism was rooted in the Modernists’ sense that the basic presupposition of the hermeneutics of continuity-in-renewal was no longer self-evident—“within the same dogma, the same meaning, the same judgment” (in eodem scilicet dogmate, eodem sensu eademque sententia).

Truth’s expressions are historically conditioned; they are never absolute, in the sense of wholly adequate and irreplaceable. The nouveaux théologiens acknowledge that point; hence their distinction between unchanging truth and its formulations. Where the Modernists and nouveaux théologiens differ is over the claim that inadequacy of expression implies inexpressibility of divine truth; hence, unlike the nouveaux théologiens, the Modernists reduced truth to its changing historical and linguistic expressions.

Thanks to a fixation on the historical-factual process, and the corresponding idea that truth-claims do not transcend the times but are entangled with the historical process in all sorts of way, a Neo-Modernism has surfaced in the so-called “new paradigm,” or “pastorality of doctrine” approach of Richard Gaillardetz and Christoph Theobald, S.J.

Theobald, for example, collapses the distinction between the substance of the deposit of faith and its formulation into a historical context, without attending to the “Lerinian” subordinate clause – eodem sensu eademque sententia – while also dismissing the notion that unchanging truths and their formulations may be distinguished within the deposit of faith. And Theobald does not hesitate to draw a dramatic conclusion: the substance of the deposit of faith as a whole is “subject to continual reinterpretation [and re-contextualization] according to the situation of those to whom it is transmitted.” This “pastorality of doctrine” approach, of which one can hear echoes in some interventions at Synod-2018, is a Neo-Modernism because it expresses a merely instrumentalist view of doctrine, in which doctrines are not absolute truths, or objectively true affirmations; in fact, doctrines don’t make assertions about objective reality at all. Thus Neo-Modernism forfeits the distinction between faith (fides quae) and its content in statements of truth (propositions whose truth-status bear a relation to objective reality). For the Neo-Modernists, the content of faith is always derived from faith’s experience of God. So that content is only a product of theological reflection upon this faith, with doctrines mediating that experience in secondary formulations. In sum: there are no revealed truths.

The Lérinian way of interpreting Vatican II acknowledges that the various pronouncements made by the Church in any given era reflect the historical setting and situation of the moment. How, then, exactly, is a single and unitary revelation of revealed truths homogeneously expressed, according to the same meaning and the same judgment, given the undeniable fact of historical conditioning?

Yves Congar, for one, has argued that the distinction between the permanent meaning and truth of dogmas, and their historically conditioned formulations (which can be subject to correction, modification, and complementary restatement), summarizes the meaning of the Second Vatican Council. Here we find the crucial difference between not only the nouvelle théologie, on the one hand, and both Modernism and the Neo-Modernism of the “pastorality of doctrine” approach, on the other, but also between the nouvelle théologie and Neo-Traditionalism. Modernism, Congar wrote, identified the theological problem posed by “variations in the representations and the intellectual construction of the affirmations of faith.” The nouvelle théologie solved this problem, he argued, by “distinguishing between an invariant of affirmations, and the variable usage of technical notions to translate essential truth in historic contexts differing culturally and philosophically.”

Given this distinction, the Church can avoid the trap of dogmatic relativism, into which the Modernists and now the neo-Modernists (with their “new paradigm”) have fallen. The Lérinian way of interpreting Vatican II stands firmly against relativism about truth, and firmly for truth’s permanence.

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD continues to interview Catholics whose work should be of interest to Synod-2018 and who, in a better-ordered synodal process, would be in Rome working with the Synod fathers.

Today’s interview is with Jason Simon, Executive Director of The Evangelical Catholic, a national ministry equipping Catholics to launch movements of evangelization. With a Master of Divinity from the University of Notre Dame and over twenty years of experience working in parish and campus ministry, he oversees The Evangelical Catholic’s expanding programs, including its online learning systems: Reach More™, a coaching system for leadership training, and the C2C Discipleship System for lay formation. With The Evangelical Catholic, he has consulted with priests, staff, and lay leaders from over 150 parishes and college campus ministries. He lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with his wife and six children.

The Evangelical Catholic (EC) is a lay apostolate based in Madison, and currently serves 60 parishes, 22 campus ministries, and 5 U.S. military installations around the world. Under The EC’s direction, local coordinators at these ministries have launched evangelical movements to train over 1500 lay leaders, and this fall, these leaders are reaching over 5000 people with the Gospel, leading them in a personalized apprenticeship of robust discipleship.

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD: How would you describe “The Evangelical Catholic” to a Synod of Bishops, if you had the chance? How did you start and what do you do?

JASON SIMON: The Evangelical Catholic was founded in 1998 by a married lay couple who longed for lay Catholics to experience the joy of being united in fellowship through evangelical mission and fervent discipleship. They began by leading an evangelization small group at their parish that gave birth to other small groups. These groups continued to multiply as members of small groups felt called to reach more people by leading their own group. Soon, a movement of evangelization was in motion, drawing more and more people into discipleship and joyful community.

The local Catholic campus ministry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison soon asked whether the founders could launch a movement in the same way among college students. My wife, Grace, and I were among those who rallied to this new initiative. We were good friends and mentees of the founders. Soon after we started, the campus ministry that once sang Beatles’ songs during communion was regularly seeing students experience transformative conversions through the witness and apprenticeship of zealous peers.

Today, The Evangelical Catholic inspires, trains, and supports Catholic leaders to launch and drive dynamic movements of evangelization in their local communities. We do this through a variety of coaching and consulting packages and an online learning management system called Reach More(TM). In general, our staff spends one hour per week coaching local leaders to launch and drive a movement of evangelization that mirrors the Mission Process of Jesus. Local leaders spend 15 hours per week putting our coaching and content into action to launch the movement using Jesus’ process. Jesus started small by deeply forming and training 12 men, he sent them on mission, shepherded them when they returned, and allowed the movement to grow as more people wanted to follow him.

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD: As you survey the American cultural scene, what are the biggest obstacles to the effective evangelization and catechesis of young adults?

JASON SIMON: Pluralism and individualism have radically reduced the power of cultural identity to pass down Christian identity and give people time to experience Jesus as Catholics. Previous generations had more time to eventually experience Jesus in the birth of their kids, struggles as parents, death of loved ones, etc. Now, teens and young adults are choosing much earlier to leave the religion of their childhood – if they have never experienced it in a personal way. Parents have not adjusted to this new reality and still think that occasional vocal prayers before meals and at bedtime – as well as periodic Mass attendance will be enough to keep their kids Catholic (if they even care). Without a personal encounter with Jesus, most young adults will not continue in their Catholic faith.

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD: What in the Church, or what about the Church, is the biggest obstacle to evangelization today?

JASON SIMON: The Church is trying to reach young adults primarily by getting them to come to events (Theology on Tap, Young Adult groups, youth groups, retreats, etc.). Event-based outreach and catechesis takes away the burden of thick substantive formation for the laity. Events allow the ministry professionals to control the delivery of content. Lay people need only to invite friends. But the most effective transference of the Gospel is person to person. It is in one-on-one or, at largest, small groups that our hearts burn and we are apprenticed into deeper discipleship. The program/event mentality is stifling the kind of formation and empowerment of lay people that will set the world on fire.

LETTERS FROM THE SYNOD: Can you offer some examples of your evangelizing work that others might find useful in their own attempts to bring the Gospel to young adults?

JASON SIMON: The Holy Spirit is faithful to reveal Jesus in new ways to people in the context of environments of friendship through his word, connected to his sacraments. When we gather young adults on a weekly basis to experience Jesus together and grow in deep friendship, just as the early Jesuits gathered regularly around St. Ignatius of Loyola in Paris, the Holy Spirit causes hearts to burn with fire for the Gospel. This group will commit to daily mental prayer, study and memorization of the scriptures, frequent participation in the Church’s sacramental life, and an outward posture of prayer for their friends, neighbors, and relatives.

After a period of time in this formation, each of these group members will be challenged to ask the Lord to lead them to someone they know who they could apprentice more deeply in discipleship on a one-on-one basis. The General Directory of Catechesis calls this apprenticeship the necessary link between missionary proclamation and pastoral activity. Without apprenticeship, many Catholics remain spiritual babies and are in danger of losing their faith at the first hardship they encounter. When these young adult leaders lead one-on-one apprenticeship with spiritually immature Catholics, they experience the joy of watching someone experience the Lord more deeply in prayer, scripture, sacrament, and community. This experience gives them a longing to reach and apprentice more people.

This initial training group eventually splits up to go lead their own groups – to reach more people by forming trusting communities of friendship, studying the scriptures, and striving to fulfill our highest purpose in this life. These groups produce more leaders of new groups and a movement spreads and a culture of discipleship becomes normative. We have seen this happen on college campuses of different demographics and sizes, in Hispanic parishes, black parishes, suburban parishes, rural farm parishes, and now we are working on military bases to reach more enlisted men and women.

We believe that the historical movements give us a model for launching new movements among laity in the Catholic Church. Ecclesial structures can provide the environment for these movements. We are currently contracting with 84 parishes and campus ministries that are doing just this. We are also developing new tools and coaching methods to train, empower, and coach laity that can launch and drive these movements without the participation of their parish. Oftentimes, priests and lay ministry staff still do not prioritize the formation, training, and empowerment of lay people for mission. This should not stop the laity from leading dynamic evangelical personal apostolates.