Last time, in this space, we discussed the conflicted conscience Christian civilisation displayed throughout its history regarding the death penalty. Oh, to be sure, Christians have moments (many of them and often quite dark) when they are glad to be rid of knaves and other people they can do without, who never will be missed. There are miscreants and monsters, bin Ladens and serial killers and child murderers and everyday ruffians (not to mention heretics and Jews and Protestants and countless other people, guilty and innocent) that get the axe, the rope, and the sword and not infrequently fill their Christian executioners with cruel joy.

Last time, in this space, we discussed the conflicted conscience Christian civilisation displayed throughout its history regarding the death penalty. Oh, to be sure, Christians have moments (many of them and often quite dark) when they are glad to be rid of knaves and other people they can do without, who never will be missed. There are miscreants and monsters, bin Ladens and serial killers and child murderers and everyday ruffians (not to mention heretics and Jews and Protestants and countless other people, guilty and innocent) that get the axe, the rope, and the sword and not infrequently fill their Christian executioners with cruel joy.

But slowly and surely the Spirit presses on the conscience of Christian civilisation. The practices they inherited from their ancestors (and the cruelties they devised on their own) – evisceration, hanging, drawing, quartering, skinning alive, burning at the stake, drowning, pressing people to death, beheading and all the other legal forms of state-sponsored killing – lose their charms and cease to be public entertainments. Christian conscience starts to feel shame over the spectacle, because, in its heart of hearts, it feels shame over the act as it felt shame at crucifixion.

Increasingly the thought presses: “This is a person made in the image and likeness of God. Somebody’s son. Somebody’s daughter. A human being like me. Yes, they may have done monstrous things. But, well, what kind of person takes delight in watching them jerk at the end of a rope, spurt blood, scream at the licking flames? What kind of person waves a frying pan at the execution of Ted Bundy? What does the death penalty do, not just to the condemned, but to those who kill him and take dark delight in that killing? What is it doing to me, to my soul? If it’s really a commandment from God and not just a concession to human weakness, why did executioners, in more Christian times, ask forgiveness of their victims and seek to prescribe years-long penances instead of swift death?”

And so Christian civilisation starts to hide its face from the death penalty, to rein in the brutality, to feel sickened qualms about “cruel and unusual” modes of killing and to move the whole thing out of sight. Executions leave the Place de la Concorde, the town square, and the public gallows and are taken indoors, out of sight, out of mind. Eventually, every western country but one – America – abandons the practice.

In America, as we resist this universal witness of conscience in the western world and the teaching of the Church, we have turned doublethink into an art form. We compare ourselves favourably to brutal Communist and Islamic regimes that retain capital punishment as we weirdly cling to the notion that the death penalty is a “deterrent” while doing everything we can to drain it of the power to deter by privatising the whole thing. We condemn Kim Jong Un as he executes his enemies with anti-aircraft guns and the Islamic world as it holds public stonings, both of which are methods that do indeed have a deterrent effect. We politely gas, shoot, electrocute, poison, and hang people behind closed doors and far from the public eye. We insist, in our secular age, on sanitising the process by turning it into a quasi-medical procedure in which we force the one person in our society who has taken a vow to Do No Harm to administer the lethal injection and kill the patient. And as Americans press on in this weird schizophrenia, tardy in relation to the rest of the civilised world, an increasing number of Christians in our post-Christian country wonders if it has made some fundamental mistake, and starts to rethink what “made in the image and likeness of God” could ultimately mean and whether there is a better way to think about this.

In short, 20th century Christian civilisation tardily, and in fits and starts, probes the idea that the law was made for man, not man for the law, and realises more deeply that, in the words of the Church, the human person is the only creature God has willed for his own sake (Gaudium et Spes 24). Americans begin to think and feel in their bones about the death penalty that “from the beginning, it was not so” – that the thing to do with Cain is spare him, not slaughter him, if possible.

At the same time this is happening in Europe and the Anglosphere, and (far more slowly) in America, events in the world were acting as a catalyst for the Church to radically re-evaluate the prudence of giving the state the power to kill. For in the 20th century there arise, one after another, the massive murder machines of Nazism, Communism, and various other inhuman regimes (including our own abortion culture in the West) devoted to massacring their own citizens in pursuit of some other end (it matters not what that end is). The scarring horrors of seeing state power so radically abused forced many people to conclude that the exercise of such power is simply too great a risk. Particularly since, even in a relatively just state, the imprecision of the criminal justice system and the reality of wrongful convictions inevitably means that acceptance of the death penalty means saying, “Better the innocent should die than the guilty should live.”

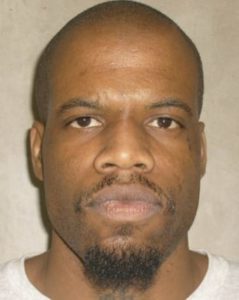

This question is only more acute in the United States, given that the US, the only country in the first world to still cling to the death penalty, is now the largest prison state on earth, dwarfing Stalin’s Gulag and housing fully 2.24 million Americans comprising 22% of the world’s prison population with a vastly disproportionate number of them being people of colour. The obvious priority – particularly for a gospel that proclaims liberty to the captive – is not “How can we send as many people on death row to their doom as quickly as possible?” but “Might we be making a mistake somewhere? Is it worth the life of a single innocent human being to slake our thirst for the blood of the guilty?”

In sum then, the Church has always recognised that there was wiggle room with respect to capital punishment. To be sure, she has never said that capital punishment was intrinsically immoral as abortion or the taking of innocent human life is. But she also never taught that murder demanded the death penalty (or she could never have prescribed the lengthy penances of antiquity). And since she was never under a divine demand for the death penalty, she finally concluded that while it is not intrinsically immoral, refraining from inflicting it is still the best and most prudent course of action whenever possible.

Which brings us back to the question of “retributive justice” – of which more next time.