Prison Journal, Volume 2 – The State Court Rejects the Appeal, George Cardinal Pell, San Francisco: Ignatius Press in conjunction with Freedom Publishing, 319 pages

A standard work on many secondary school English syllabi is To Kill a Mockingbird.

The average student reading this work in a liberal democracy such as Australia, which values the rule of law and a rigorous judicial process, is typically stunned and disgusted at how the accused Tom Robinson could possibly be found guilty of the crime with which he is charged, when the evidence clearly indicates that such a verdict is unreasonable.

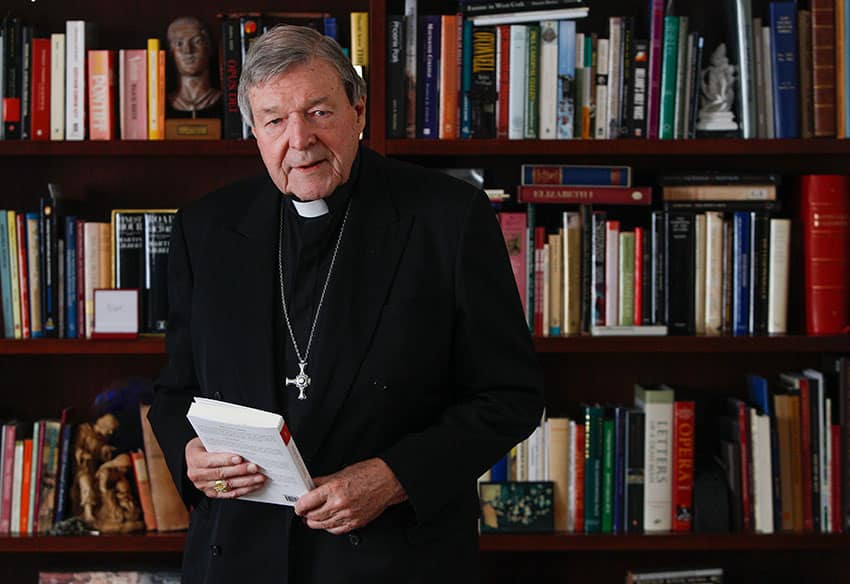

Sadly, George Cardinal Pell, formerly Archbishop of Melbourne and of Sydney, and more recently Prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy (2014 – 2019) at the Vatican, was imprisoned for crimes for which he should never have been found guilty.

This is the most recently published volume in a three volume set, and covers the period from the start of Week 21 (Sunday 14 July 2019) to the end of Week 40 (Saturday 30 November 2019) of his imprisonment.

“The portrait of Pell that emerges from his reflections is of a man of deep faith, whose faith sustained him.”

As the subtitle of this volume indicates, this covers the period leading up to the appeal before the Court of Appeal in Victoria, its decision to uphold the initial verdict, and the period following it.

One simply cannot imagine what Pell, a man who should never have been found guilty in the first place, endured during his 404 days of incarceration.

Given the nature of the crimes of which he was found guilty – namely the sexual abuse of minors – Pell typically spent 23 out of every 24 hours in his cell for his own protection, with short exercise periods outside his cell away from other prisoners.

This meant that his contact with fellow human beings, something most of us take for granted, was denied to him.

The portrait of Pell that emerges from his reflections is of a man of deep faith, whose faith sustained him. Central to his faith life is the person of Jesus Christ.

As Pell came to terms with the trauma of his appeal being rejected by the Court of Appeal in Victoria, he reflected on the sufferings of Christ, uniting his suffering to Christ’s sufferings.

For example, he makes frequent references to the scripture passages and works from the Church Fathers and other Christian writers in the Office of Readings. In many instances, these became for him a catalyst for reflection on his experience of imprisonment as well as on the wider church and society.

This spiritual reading was complemented by reflections/sermons written by Sr Mary McGlone, an American religious, which Sr Mary O’Shannassy, the prison chaplain brought to Pell in her weekly visit, during which she conducted a para-liturgy at which he received Holy Communion.

Pell openly states that being unable to celebrate Mass whilst in prison was a spiritual burden he had to endure. Furthermore, in the 20 week period this volume covers, he was able to attend Mass only once by special arrangement.

Pell was able to draw spiritual comfort from viewing Mass for You at Home, aired at 6am on a Sunday morning; however, it was not until he was given an alarm clock by one of the prison wardens that he was able to wake up consistently in time for the early morning screening. He usually watched the preaching of two evangelical preachers, Pastor Brian Houston (Hillsong Church) and Joseph Prince, noting that he preferred Prince’s overall approach as it was more explicitly Christocentric.

“Pell’s empathy for suffering people is also manifested by the way in which he reached out to fellow prisoners who wrote to him …”

He critiqued their messages, identifying points in their sermons with which he agreed, and disagreed. However, Pell does so charitably and acknowledges that both men are formidable preachers.

One thing he notes is that both preachers draw extensively from the Old Testament. This reviewer found the descriptions of the eclectic clothing ensembles worn by Joseph Prince amusing and had the sense that Pell did as well – hence his recording of such details.

References are also made to various documentaries watched by Pell, particularly those of an historical nature, on channels such as SBS.

A keen football fan, Pell also records the various football matches he watched on his TV.

Extensive reference is made to the correspondence he received throughout the course of his incarceration, from correspondents across the globe. Virtually all the letters and cards he received were encouraging, and served to boost his morale. Pell also notes the visits from lawyers, family members and friends.

The image of Cardinal Pell presented in the pages of the journal is different from that portrayed by various sections of the media – namely an intolerant and cold curmudgeon.

Instead, the Pell of the prison journal is a man of deep compassion and concern for his fellow human beings, including fellow prisoners, many of whom are sadly affected by hard drugs; a man of deep humility, reflected for example in his acknowledgement of his human frailties and weaknesses, such as various physical infirmities.

He is also a man of deep gratitude, reflected not only in the way he describes his interactions with the prison staff, but also the way he expresses in the pages of his journal his appreciation for small things such as extra snacks given to him, and the opportunities to sweep out his cell and the exercise yard.

Pell’s empathy for suffering people is also manifested by the way in which he reached out to fellow prisoners who wrote to him, including those who asked for spiritual advice, writing extensive replies to them.

Questions have been raised by some commentators as to the extent that Pell presents his innermost thoughts in the pages of the journal.

Whilst there is some evidence that the author may subsequently have edited portions of the text – for example on more than one occasion, Pell states that he will develop an idea briefly mentioned in a future reflection – there is the sense when reading this volume and the preceding one that there has been minimal editing, and that the readers are provided with the journal as written by the author in prison.

“It ranks with other literature written by people of faith who suffered imprisonment, including Walter Ciszek, Francis Xavier Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan and Thomas More, and may prove – with the test of time – to be a spiritual classic.”

For example, the author identifies the occasions on which he had to endure the indignity of being randomly strip searched; similarly, the mundane details of his daily life recorded on almost every page such as how many squares of chocolate from a chocolate bar he consumed, are reflective of authentic life experiences.

Because such details suggest that only superficial editing has been done at a latter date, the readers can be confident that they are reading Pell’s thoughts and responses.

Prison Journal, Volume 2 is an engaging and moving read.

It ranks with other literature written by people of faith who suffered imprisonment, including Walter Ciszek, Francis Xavier Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan and Thomas More, and may prove – with the test of time – to be a spiritual classic.

However, one cannot do justice to this work by reading large chunks of it over two or three sittings in the same way that one may read a novel or a work of history.

Instead, it demands of readers to read it slowly, section by section, and reflect upon the ideas that the author raises and discusses. It would thus be a suitable basis for spiritual reading. This work is highly recommended.