Sydney:

The arrival of our first Archbishop saw a church become a cathedral and was accompanied by his vision. He desired a building that would be a focus of Christian life and a Catholic culture largely extinguished in Ireland

In September 1835, the Catholic Community of Sydney and surrounding districts welcomed Australia’s first Christian bishop, John Bede Polding, who had spent most of his life as a monk in a Benedictine house in England.

On that day, the recently-completed Saint Mary’s church became a cathedral and its bishop had particular thoughts about it.

Above all, it was to be the noble house of the Lord, a foretaste of Heaven, in which Catholics would find a tranquil refuge and where the Rites of the Church would be celebrated with beauty and dignity.

To a Benedictine, the notion of the beauty of the Sacred Liturgy was central to Catholic Faith.

However there was something more to Bishop Polding’s purpose: in colonial Australia he hoped to establish a Catholic culture, something still known in Europe, but which had been almost extinguished in the Ireland left behind by the emigrant and convict Catholics of NSW.

With these aspirations, he expended much of his energy and work to improve and adorn the cathedral and this remained a continuous focus of his efforts over the next 30 years.

In 1835, old Saint Mary’s was complete in all respects on the outside (including the glazing of its many windows).

The inside, however, was but a large T-shaped hall, with walls of exposed stone, its sanctuary plain with only an altar for the celebration of Mass.

There were no galleries and no ceilings. The floor was formed from planks of timber, while the timber rafters which comprised the roof structure and the wooden shingles which covered the outside were visible to those within.

At least four columns of Ironbark divided the interior space at the intersection between the nave and the transepts.

The Bishop privately observed that the appearance of the interior was “desolate” and set out to transform it.

The engraving on the opposite page, published in 1842, illustrates what the cathedral looked like after many of the Bishop’s enrichments had occurred.

The artist prepared his sketch from the main entrance of the cathedral, looking towards the sanctuary. We see that the interior is bathed in natural light and that timber columns, like an avenue of tress, run the full length of the building.

By these columns, the interior of the church was divided into three aisles, each approximately 3.5 metres wide.

The columns support the new ceiling, the latter constructed from planks of red cedar and formed into vaults.

It was all intended to imitate the stonework found in large Gothic churches and cathedrals.

The cedar columns and vaulted ceilings are polished and would have glowed impressively in the light.

On the right-hand side of the engraving can be seen the balustrade of a timber gallery, divided into Gothic panels. Not visible was another gallery, situated above the main entrance facing Hyde Park.

There is also a magnificent stone baptismal font in the Gothic Revival style, located in the body of the church and near the main entrance.

But something is missing: pews or seating (except for one or two closer to the sanctuary). The congregation stood and knelt throughout Mass and other celebrations on the timber floors, which would not have been so comfortable.

The most intricate of all was the distinctive treatment given to the sanctuary. The entrance to the small apse – hidden in shadows at the eastern end of the church – was divided by two columns, at the top of which were fitted elaborate ornamental timbers, shaped into archways.

In order to further enhance this focal point, these arches were filled with stained glass, which delicately glowed in the subdued light.

We see a very large timber High Altar, painted to imitate marble, and large oil paintings of sacred art, which Bishop Polding went to great trouble to acquire from overseas.

It was only a couple of years after finishing these works that Bishop Polding left on a tour of Europe, but especially Rome and England in 1840.

He was absent for two full years, seeking more priests and religious sisters to bring to Australia.

He was also looking for books to help educate his seminarians and works of art to bring back for the cathedral.

In Rome, he arranged for new Australian dioceses to be formed from the enormous territory in his charge; these were Adelaide and Hobart.

The Pope of that time, Gregory XVI, established Sydney as an Archdiocese and created Polding as its first Archbishop.

He was interested in the new Archbishop’s plan to form his vast Archdiocese around a Benedictine monastery in Sydney, where some of the monks would also minister to Catholics throughout Australia.

Old Saint Mary’s became a Monastery church, and a tradition was revived of celebrating the Divine Office in the cathedral, especially Vespers and Compline.

During his overseas journey, Archbishop Polding met the architect of a new Catholic cathedral in Birmingham, England – Augustis Pugin.

The Archbishop had been overwhelmed by the Gothic radiance and grandeur of the Birmingham Cathedral and asked Pugin to design some churches and other buildings for the far-off colony.

From 1843, new buildings began to appear on the Church land adjacent to the cathedral.

Mostly, they were additions to the older buildings (a school and priests’ residence) constructed by Father Therry 20 years before.

The additions comprised the Monastery buildings for the Benedictine Community resident at the cathedral.

A curious looking bell-tower appeared at the North end of the property in which a magnificent peal of bells from England – the first in the Colony – was hung and sounded for the first time on New Year’s Day 1844. All these, with the exception of Chapter Hall (constructed in 1845 as a school house) have long since disappeared.

The most prominent new construction, however, was a substantial addition to old Saint Mary’s which was commenced in 1851. The additions to the cathedral designed by Pugin were as ingenious as they were beautiful.

In his talented hands, a building which was rather plain and squat in proportion was to become dramatic and highly-ornamental, even though the additions added no more than 16 metres to the cathedral’s length.

The older sections of Saint Mary’s were symmetrical, identical from one side to the other, resembling an English Manor House, but the Pugin additions were replete with varied components so that the final effect was a cluster of different, but harmonious compartments, unified by its splendid Gothic ornament.

Pugin’s design would be crowned with a tall, massive bell-tower and a soaring spire reaching almost 60 metres. The work was carried out over 11 years but was also beset by a lack of money.

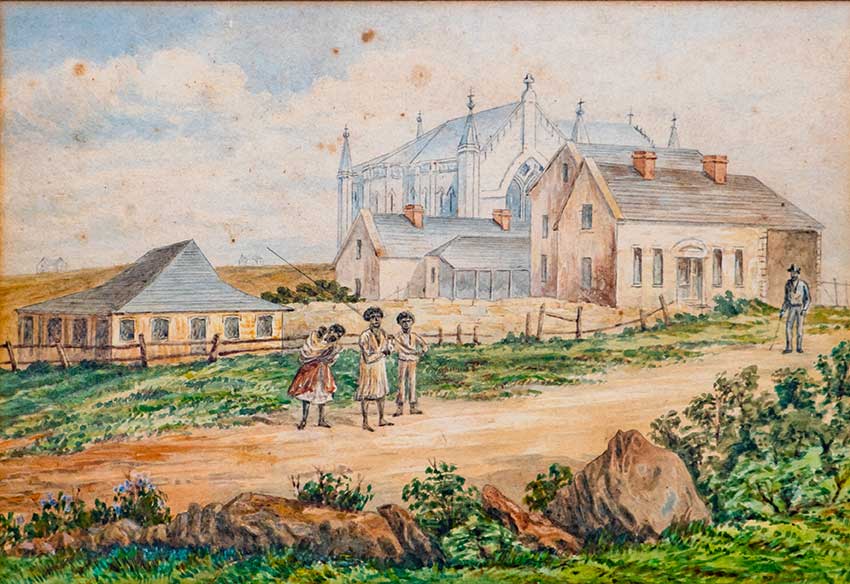

The colourised engraving below gives a very accurate idea of what this large addition to old Saint Mary’s looked like when it reached a semi-finished state in 1862.

The three-metre-tall statues standing within the facade of the extension were carved in situ by one of the Sydney Benedictine monks, Dom Jean Gourbeillon. The statue of Our Lady with the Child Jesus survives and is presently situated outside the cathedral on the College Street side.

The magnificent Gothic Revival additions have almost nothing in common visually with the old work constructed 25 years before.

Why? Although never made explicit, it seems that a much later development would have been to take down or remodel the old sections of the building and replace them with new work according to Pugin’s more refined and up-to-date design.

One engraving of the Cathedral from the 1850s suggests just this intention.

But none of these aspirations were realised, because a tragedy overtook the Catholics of Australia on the night of 29th June 1865.

Saint Mary’s Cathedral was consumed by fire, whilst thousands of Sydney-siders crammed into Hyde Park and adjacent roads to watch the conflagration, gripped by awe and horror.

By morning all only the scorched stone walls were left. More than 40 years of ongoing hard work, noble aspirations, the prayers and monetary offerings of the Faithful, beautiful works of sacred art and a grand pipe organ – all were turned to ashes in a few hours. No one was injured and no lives were lost.

Within a matter of months, as plans for a new and much-larger cathedral were drawn-up, the walls of Father Therry’s church were pulled down, except for one section of the Northern transept (see Page 11).

The magnificent facade, the design of the architect Pugin, was largely intact after the fire and it remained in place facing Hyde Park for decades until finally it made way for the expansion of the new Saint Mary’s after 1914.

It was planned that the old stonework would be re-erected elsewhere on the Cathedral precinct as the facade of a proposed Cathedral Hall, but that plan, quite sadly, came to nothing. To this day, no one knows for certain what happened to the stones of old Saint Mary’s.

Related