What is the problem? Why is the National Health and Medical Research Council conducting a ‘public consultation’ about the ethical and social questions raised by a proposal to change the law to allow ‘mitochondrial donation’? After all, mitochondrial donation offers the prospect of allowing couples to avoid passing on mitochondrial disease to their offspring. Mitochondrial disease is an inherited condition which can cause serious health problems and, in relatively rare cases, can radically reduce a young person’s life expectancy. No wonder, then, that parents wish to avoid passing on the faulty mitochondria that can cause the condition. What, then, is the problem?

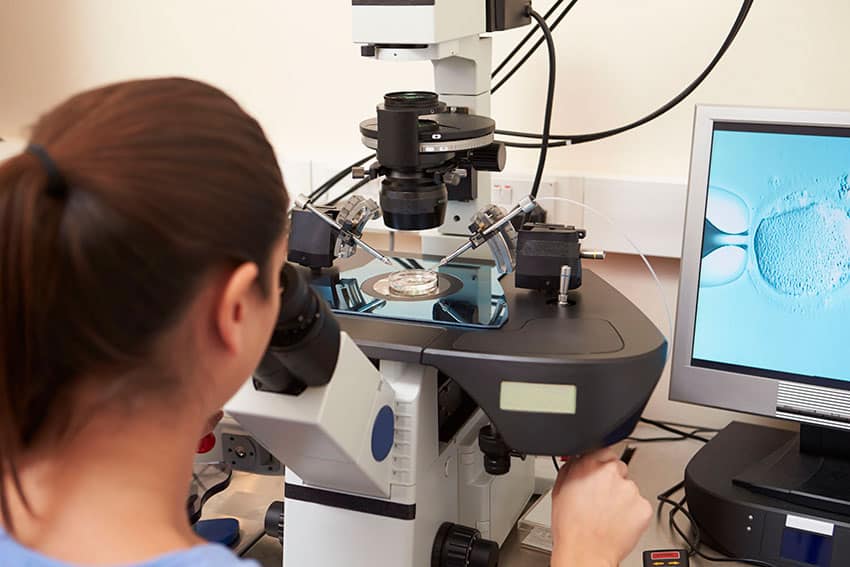

The science of 3-parent IVF

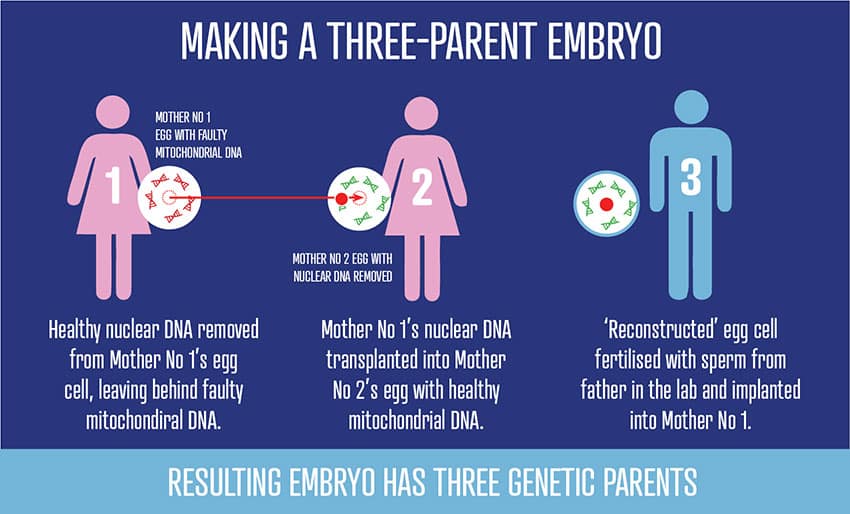

A little background. Though most of our genes (our ‘nuclear’ DNA) come from both our parents, a very small percentage of them (our ‘mitochondrial’ DNA) come only from our mother. Though few in number, these mitochondrial genes are critical to the normal functioning of all our cells. Thus the entirely-understandable desire of women with faulty mitochondrial genes to avoid passing them on. The difficulty arises when affected women want to have their ‘own’ children, children to whom they are genetically related.

Technologies which would replace the affected mother’s faulty mitochondria with healthy mitochondria from another (‘donor’) woman might enable this. These technologies include ‘maternal spindle transfer’ (MST), ‘pronuclear transfer’ (PNT), ‘polar body transfer’ (PBT) and ‘germinal vesical transfer’ (GVT). One way or another, the technologies would all involve creating human embryos with DNA from three people, father, mother and donor. It’s because the use of these technologies would not only require changes in the law but also pose serious ethical and social questions that the NHMRC wants to know what we Australians think.

Significant legal issues

First, the necessary changes to the law would be significant. Since 2002, when the Commonwealth abandoned its time-honoured prohibition on the creation of human embryos for purposes other than implantation in a woman, researchers have been able to apply for a licence to create human embryos for research purposes (so long as the embryos would subsequently be destroyed!): that would need to be changed. At the same time, the Commonwealth explicitly prohibited any form of germline modification (that is, any modification of an individual’s genome which could be inherited by that individual’s descendants). Clearly, any change to the law regulating ‘reproductive technologies’ would be ethically controversial.

There is the question of the risks to the ‘to-be-born child’. Almost everyone agrees that very little is currently known about the likely impact of mitochondrial changes on the rest of the child’s genome, that is, on the remainder of the genetic instructions that influence the way the child grows and develops into an adult. We therefore need to consider whether mitochondrial donation would violate the duty of parents not to subject their children to undue risks.

Risks to future generations

But not only are there unknown risks to the to-be-born child. There are unknown risks to future generations, for the altered mitochondria may be passed on, with unknown effects, to an individual’s descendants.

Then we face the ethical objection to ‘fragmenting motherhood’. Some years ago, when some argued that cloning should be an available reproductive choice for those who desire it, others rejected reproductive cloning, arguing that every child is entitled to a natural (untampered-with) biological heritage, that is, to be conceived from a natural sperm from one, identified, living, adult man and a natural ovum from one, identified, living adult woman. Mitochondrial donation would violate that entitlement. A child born after mitochondrial donation would have a biological relation not only to his or her father and mother, but also to the donor of the healthy mitochondria.

Many of those born of anonymous sperm donation are now convinced that, in the circumstances of their being conceived, they were grievously wronged. We should learn from that experience and not assume that a child born from an embryo containing the DNA of three people would have consented to this arrangement. Remember: when the great American philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre was asked whether we should design our descendants, he argued that the paradox was that, when they grow up, they may not be grateful to us for our having done so.

The desire to have healthy children is as understandable as it is universal. But the question for the Australian community now is whether enabling couples to satisfy that desire by the method of mitochondrial donation would come at too great an ethical price for it to be worthy of the community’s support.

Related:

- Three-person IVF causes grave concerns

- Dr Margaret Somerville: ethical issues caused by 3-parent IVF