At a time of global conflict, a visionary genius creates a device whose full implications only become clear once it is unleashed upon the world, plunging humankind into a future of endless paranoid rivalry that risks civilisation itself.

I refer, obviously, to the invention of the first Barbie by Ruth Handler in 1959, and the debate over gender stereotypes that has raged ever since, culminating in the release of Greta Gerwig’s fluorescent magnum opus Barbie, starring Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling.

Gerwig and her partner and screenwriter Noah Baumbach’s plastic fantastic feminist creation myth, in which an opening riff on 2001: A Space Odyssey gives way to a plot drawing on mythical visions of ideal souls falling to Earth, has already attracted praise from girlbosses and outrage from critics for its purported anti-men message.

Putting aside that Barbie would never portray a view of gender relations most Catholics could get behind, the interested viewer will instead find a film that oscillates wildly between irony and sincerity as it deconstructs both “the patriarchy” and contemporary feminist ideals.

It’s also (mostly) just plain fun, with sets and costumes pulled straight from last century’s cellophane wrapper.

The film begins in Barbieland, where Barbie (Margot Robbie) leads an ideal existence with her friends Barbie (Issa Rae), Barbie (Dua Lipa), Barbie (Emma Mackey), Barbie (Alexandra Shipp), Barbie (Sharon Rooney) and so on.

The barbies give each other Nobel prizes, explore space, play dressups and hold dance parties on weeknights—it’s bliss, before the fall.

Their counterparts are the himbo Kens, fronted by Ken (Ryan Gosling) and his nemesis, Ken (Simu Liu). The Kens only exist for the gaze and attention of their benevolent female overlords, and squabble among themselves for the Barbies’ attention.

The Barbies live in perfect plastic dreamhouses, while the Kens live out of sight and mind. As Robbie tells a forlorn Gosling as she sends him packing from a sleepover with the Barbie president, “Every night is girls’ night.”

Yet there is trouble in heaven. Robbie has a sudden moment of existential dread in the middle of a choreographed disco number, and soon finds she has flat feet, bad breath and cellulite.

The back-and-forth about “patriarchy” versus “girlbossing” takes place in a plastic world, and Gerwig seems to imply that these are plastic concepts fit only for the dollhouse, rather than real life.

She is plunged into a crisis that leads her out of Barbieland into “the real world,” with Gosling tagging along, to meet her maker. Along the way Barbie finds that her visions of mortality are caused by the unhappiness of Gloria (America Ferrara), who has lost faith in Barbie because of her angsty teen daughter and dull job working for toy giant Mattel.

Barbie returns to Barbieland to show Gloria what dreams are made of, only to find that Ken, having learned about “patriarchy” in the real world, has turned heaven into a cowboy and monster truck themed hellscape.

The naive Barbies, entranced by the Kens’ frat-boy antics, must become self-aware about the difficulties of real-world female life, liberate themselves, and build a new kind of dreamland.

Robbie, Gosling and the rest of the cast clearly enjoyed making this Legally Blonde-meets-Origen parable, in which Barbie, the ideal image of last century’s femininity, must literally come down to Earth and confront her failure to be the champion for women she was created to be.

Ferrara’s impassioned monologues about the contradictions of life as a woman are the moral centre of the film, but are also a cry for society to value ordinariness, motherhood, ageing, and family—all dimensions of life put through the Procrustean bed of the “have-it-all” Barbie dreamhouse.

Barbie also slyly intimates a deeper critique of our culture’s current gender rivalry by setting this whole drama within the context of a movie about toys—a point that seems to have been lost on many critics.

The back-and-forth about “patriarchy” versus “girlbossing” takes place in a plastic world, and Gerwig seems to imply that these are plastic concepts fit only for the dollhouse, rather than real life.

In this sense Barbie’s whole parade of disco fun, fake tan and neon rollerblades puts the viewer at an ironic distance from the all-consuming gender debate, and asks whether our playing at Barbies and Kens has alienated us from our actual need to live—and for men and women to rediscover themselves by leaving these conceptual dolls behind in the toybox.

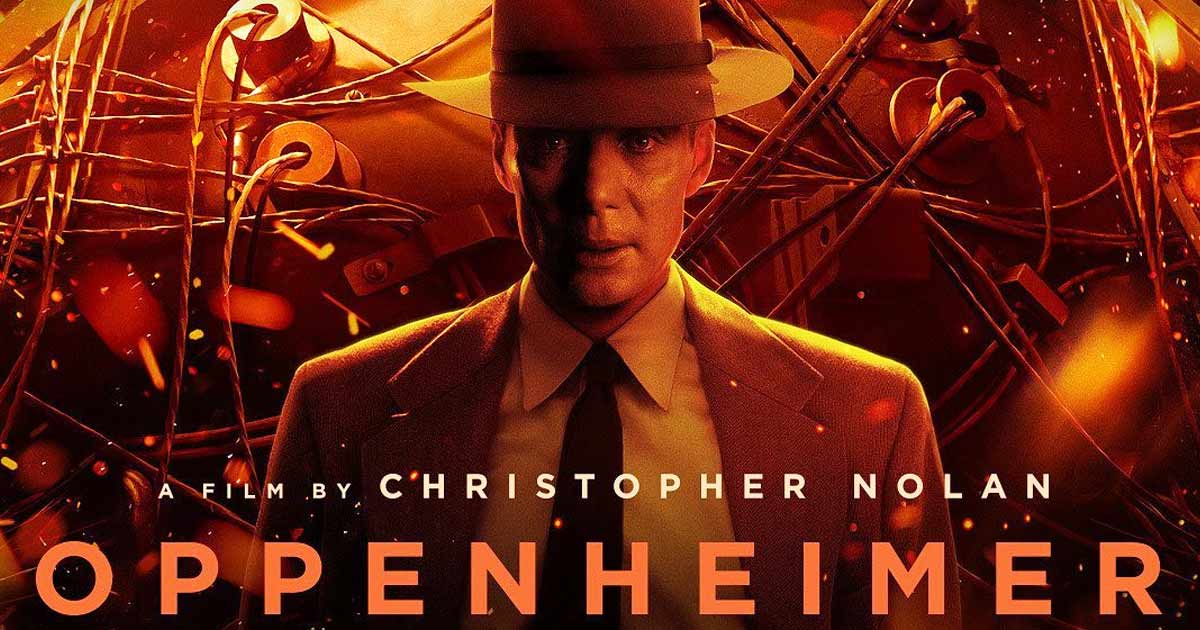

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer—his three-hour adaption of American Prometheus, the Pulitzer-winning biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the nuclear bomb”—is a stylistic world away from Barbie.

The “new physics” immediately cracked open the shell of reality to reveal the apocalypse, the bomb, and it was inevitable that the weapon would be brought into existence.

As with many of Nolan’s other films, Oppenheimer is built around a framed narrative; the race to beat the Nazis to the atomic bomb is nestled within two courtroom dramas, one in which J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy, in career-defining form) is subject to a McCarthyite inquisition for his Communist affiliations during the Manhattan Project, and a second that sees Atomic Energy Commission chairman Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr) grilled by a senate committee prior to his appointment to cabinet.

Like Inception, Tenet, Memento and other Nolan originals, Oppenheimer is not a “realist” film, and is certainly no documentary—it has a typical Nolan misdirection at its real centre. Put bluntly, it’s not ultimately about the atomic bomb.

The thrilling race to develop the bomb at a secret facility at Los Alamos, culminates in the Trinity nuclear test two-thirds through the film. Oppenheimer’s famously (mis)reported quotation from the Bhagavad Gita—“I have become death, destroyer of worlds.”—is only the end of the second act.

And the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not portrayed, but are only relayed to the scientists by President Truman’s (Gary Oldman) radio broadcast.

Rather the film’s pivotal moment is a conversation between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein (an enigmatic Tom Conti) at Princeton University, after the war, while Strauss is recruiting Oppenheimer to head up a prestigious physics department.

The conversation, seen but unheard by Strauss, sparks his paranoia, leading him ultimately to mistrust Oppenheimer and persecute him in the hearing that makes up the lion’s share of the film’s almost unforgiveably slow third hour.

This paranoia returns to hurt Strauss, who gets torn apart by the gears of his own political machinations in the film’s culminating scenes, leading ultimately to his rejection as a senate candidate and career disgrace.

The political framing of the Manhattan Project massively and brutally relativises one of the film’s major themes, Oppenheimer’s moral qualms about the bomb and his advocacy for nuclear arms controls after the war. As President Truman tells Oppenheimer in the Oval Office, “Do you think anyone in Hiroshima or Nagasaki cares who built the bomb? They care who dropped it.”

“Hiroshima isn’t about you,” he sneers, telling his aide, “Don’t let that crybaby back in here again.”

Nolan’s blunt, visionless politicians and lawyers are set against the mystical, prophetic physicists in a way that is almost Biblical; as Nils Bohr (Kenneth Branagh) says in one of the film’s many oracular utterances, “You can lift the stone without being ready for the snake that’s revealed.”

The snake, as Nolan reveals in his final scenes, is not nuclear destruction, but rather the paranoia and rivalry between Russia and US unleashed by the bomb; by inventing the bomb, Oppenheimer and his team have freed the worst human passions from all moral limits, leading to a world of negative meaning where politics and law can not “convict, only deny.”

This theme continues Nolan’s habit of making radical films with conservative moral messages, a technique perfected in his Batman trilogy.

Yet it also subtly undermines Oppenheimer, insofar as Nolan looks away from the full implications of his physicists-as-prophets theme. Indeed, as the film itself admits, from the moment the atom was split the world’s physicists knew the profane implications of their discovery.

As the film explores in its most haunting scenes, the “new physics” immediately cracked open the shell of reality to reveal the apocalypse, the bomb, and it was inevitable that the weapon would be brought into existence.

As Murphy says by way of apology to the scientists reluctant to join the Manhattan Project, “I don’t know if we can be trusted with such a weapon, but I know the Nazis can’t. We have no choice.”

As the most penetrating philosophers and theologians saw after the war, the true significance of the bomb was not that it was a moral abomination; rather it was a limit we knew we were forbidden to cross, but were compelled into transgressing because of our enslavement to science, method and technology.

Ultimately this is where Barbie and Oppenheimer meet, in the vision of a fallen world where despite our best efforts, our “toys” beguile and enslave us, and lead us to reorganise our societies away from God and human needs to the production of idols, in both plastic and uranium.