Two priests in a penal colony

Two young priests from Ireland arrived in Sydney on 2 May 1820 with both zeal and enthusiasm. They had volunteered to be missionaries in the far-off Penal Colony of New South Wales. The British Government had formally appointed them as Chaplains and when they arrived, the local Governor, Major-General Lachlan Macquarie, recognised their credentials and gave them instructions on how they were to conduct their work. These were the pioneers John Joseph Therry and Philip Conolly.

They were given lodgings by some Sydney Catholics near The Rocks as they settled in to their new pastoral charge. Soon, they would have understood that their flock was almost entirely composed of convicts or former convicts and amounted to around 7500 men, women and children spread throughout Sydney and its regions. Where to begin?

Mass and the Sacraments had begun to be celebrated by the two in private residences, but they lost little time in determining that Catholics needed a permanent and fitting place of worship. There would be a better chance of boosting the practice of the Faith once a permanent church had been built. But most of all, they believed that God should be honoured with the construction of a permanent place of worship.

A meeting is called

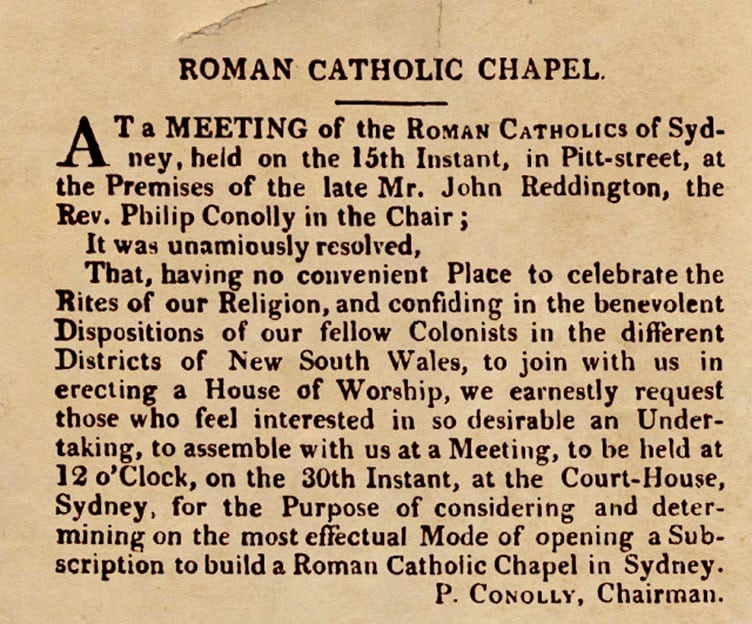

And so, readers of the Colony’s newspaper, The Sydney Gazette would have been surprised to find an announcement prominently placed on page 2 of the 17 June 1820 edition. The Gazette reported that a meeting of Roman Catholics two days earlier had unanimously resolved to hold a public meeting at the Sydney Court House at the end of June to begin fundraising for a Catholic Chapel.

This was something different for the inhabitants of the Colony. Their experience of Catholicism was of a circumscribed, private religion, which had even proved politically subversive. The Church of England was the official form of Christianity in the Colony.

The preliminary meeting, which The Gazette mentioned had been held at a premises in Pitt Street, the property of John Reddington. Reddington had come to Australia as a convict in 1800 for his part in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. He had done well for himself and owned a premises where alcohol was served under licence – a pub named The Harp Without a Crown. The premises was also a grocery store and it was most likely a place frequented by Irish Catholics.

The journey begins

Although he had died four years before the arrival of the priests – the beneficiaries of his estate still owned the Pitt Street building. They were Catholic and willing to offer their property for Church purposes. The building – most likely made of timber – was near the corner of Pitt and Market Streets, where the Sydney Tower now stands. Mass had also been celebrated in this premises in the month since the two priests arrived in Sydney.

The proposed meeting took place in the Sydney Court House (now ground floor rooms in Parliament House in Macquarie Street) on 30 June and an extensive report appeared the following day in the pages of The Gazette. Unfortunately – and probably deliberately – the report does not indicate how many attended. From this, it would be safe to assume numbers were low. The writer of the report was at pains to point out, however, that the meeting was attended by “all the Respectable Catholics of the Colony”.

In the long-winded prose found in newspapers of those long-gone days, a series of 11 resolutions was recorded, which included thanking various persons for their benevolence.

More practically, however, it was resolved that Catholics were to “unite with their clergy to build a House of Divine Worship in the Town of Sydney”. To this end, a Committee was formed at the meeting, led by Fathers Conolly and Therry, which would “select a site for the building, administer the contracts, manage the finances for its building and authorise fundraisers.”

Seeking donations

A sub-committee was also to be formed to oversee donations from non-Catholics. From those present at the meeting, seven Catholic laymen were appointed to the Committee: James Meehan, William Davis, James Dempsey, Edward Redmond, Patrick Moore, Michael Hayes and Martin Short – all former convicts.

In their different ways, they had been accused of insurrectionary crimes in the patriotic Uprising on the West Coast of Ireland in 1798 aimed at overthrowing British Rule. Each had arrived in the Colony of NSW in 1800 or 1802. John Reddington was also among their number.

All had eventually received a conditional pardon by the Colonial Government and had become successful businessmen, so that by 1820, two decades after their transportation from Ireland, they had become “the respectable Catholics of the Settlement”. They had come to know each other very well from their 20 years in the Colony. The Treasurer of the Chapel Building Committee, however, was neither Catholic nor a former convict, but from Armagh in Northern Ireland and a prominent figure in the Colonial Government of Lachlan Macquarie.

Support from a key personality

His name was John Thomas Campbell. He had arrived in Sydney with Governor Macquarie’s entourage in 1810 and was immediately appointed the Governor’s Secretary. For 11 years he was Macquarie’s chief assistant in the administration of the colony, his intimate friend and loyal supporter.

It is significant that a man as prominent and well-connected as Campbell became the Committee’s treasurer. It was obviously strategic – he would be instrumental in attracting support from a broader range of Colonists than Catholics. That he accepted the nomination indicates his personal support for the Chapel project and his good will.

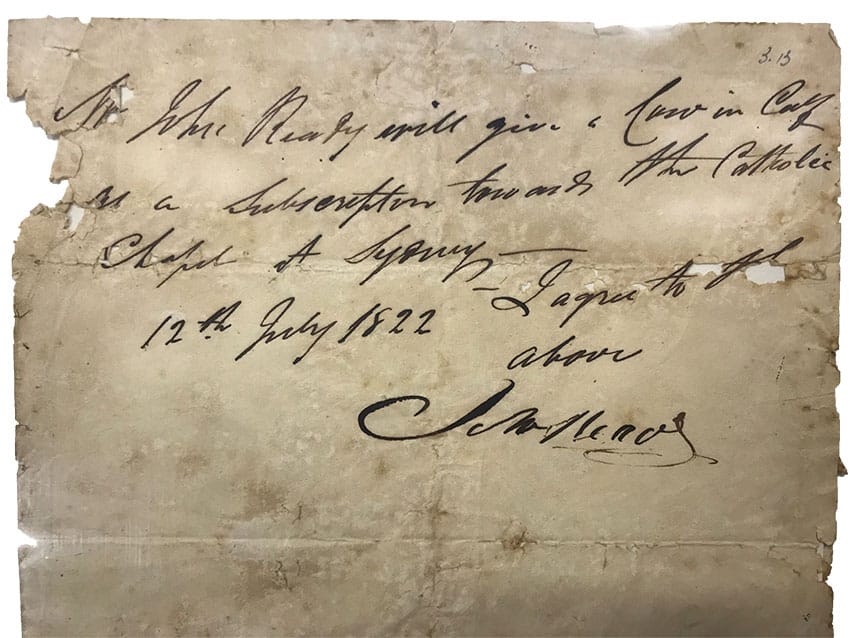

The Committee lost little time in encouraging donations to the Chapel building fund. Mr Campbell placed an advertisement about the building of the Chapel in The Sydney Gazette on 2 September 1820, in which he advised that an account had been opened at the Bank of New South Wales “for the purpose of receiving subscriptions” and he requested “that persons of every Religious persuasion, disposed to contribute to this laudable Object, will make their subscriptions there as soon as possible, in order to the Committee being thence enabled to commence on the purposed building.”

Staying focused

But Campbell also sounded a note of caution to those suggesting that there should be more than one Chapel supporting the needs of Catholics outside Sydney. Not only were most of the Colony’s Catholics located in Sydney but “the circumstance of the Roman Catholics of New South Wales being much more numerous than wealthy” it was best they confine “their contributions for the present to the single Object of erecting a Chapel in the Town of Sydney.”

Fourteen months later, the fundraising efforts in attracting donations to the Chapel building project had proved successful, with the notice filling half a page in The Sydney Gazette of 1 December, 1821.

Fourteen months later, the fundraising efforts in attracting donations to the Chapel building project had proved successful, with the notice filling half a page in The Sydney Gazette of 1 December, 1821.

The substantial sum of £628 had been donated in the course of almost 18 months – a remarkable figure for the time. More interesting than the pounds, shillings and pence are the names of those who appear in this list, the great and the good of the Colony at this time. These are names we are familiar with from streets, suburbs and towns, such as Erskine, Jamison, Goulburn, Piper, Wentworth, Druitt, Wollstonecraft, Oxley, Cordeaux and Macquarie. These were all prominent and respected non-Catholics and all had made generous donations.

From “the respectable Catholics of the Settlement”, some had made very generous donations: William Davis and his wife Catherine, each gave £50. But many non-convict Catholic colonists had not contributed, while many more, being convicts, were in no financial position to do so. Still others, having no cash to offer, offered livestock and other goods. The “Widow’s mite” of the Gospel story comes to mind.

Related