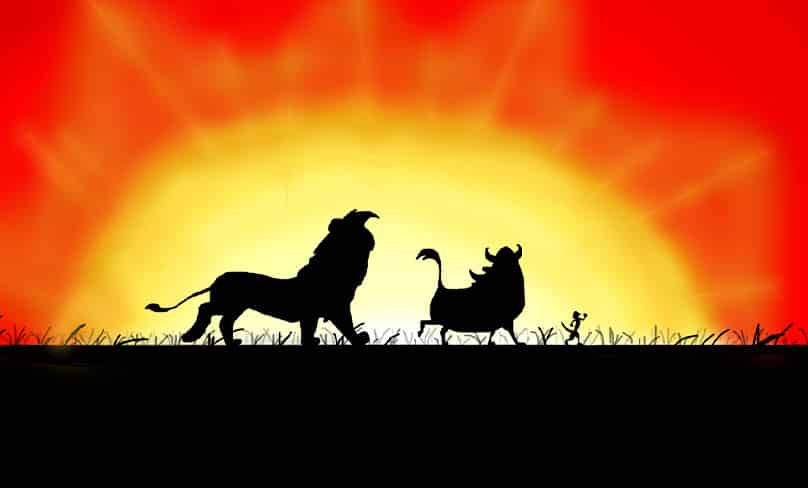

Unless you live under Pride Rock, you would have heard that Disney’s “live-action” remake of The Lion King premiers today in theatres across the country.

The original 1994 film, produced during Disney’s Renaissance period from 1989-1999, has grossed over $968.5 million worldwide, is the third highest-grossing film by Walt Disney Animation and has a Broadway musical adaptation that has become the third longest-running show and highest grossing Broadway production in history.

The worldwide success of The Lion King is due to its beautifully crafted story that touches the hearts of audiences on so many different levels. One, which some may not immediately realise, is the spiritual.

The film’s iconic story is influenced heavily by the Christian Bible but is filled with Catholic truth and symbolism.

Take the very first scene.

The opening sequence is much like the beginning of Genesis, depicting the beauty and miracle of God’s creation.

Animals from all walks of life emerge from the darkness of their slumber into the light, making their way across the breathtaking landscapes of Africa to Pride Rock.

Pride Rock is at the centre of the kingdom and, as Dr Jordan Peterson of all people points out in an online video, represents a cathedral in its form, position and importance.

Peterson also identifies the rock as symbolic of tradition: carved into its face is the law which governs the African grassland kingdom.

As the film progresses, a pair of golden lions, symbolising divinity, have a child who is to be the hero of the story.

This divine child is baptised by the Shaman (Rafiki) who holds him up for all the creatures to see.

The parallels with Christian baptism and a priest’s elevation of the Eucharist are obvious.

Just as the Catholics fall on their knees before the Real Presence, all the creatures spontaneously bend down to worship this divine cub.

Meanwhile, roles are remarkably evocative of the biblical characters of Genesis: Mufasa and Scar respectively symbolise good and evil, God the Father and Satan.

Scar is depicted as a thin weaker lion living in a dark cave eating on whatever crawls in. He is conniving and sinister with a jet black mane, dull coloured fur, scar over one eye and a malevolent voice that actor Jeremy irons does to perfection.

The parallel between Scar and the Evil one is evident when Simba tells him about the shadowy place that his father forbade him to go.

Just as the devil tries to undermine the word of God the Father so too does Scar with Mufasa’s word as he tempts Simba to break his father’s command by telling him the shadowy place is an elephant graveyard filled with danger, ensuring the curious cub will go there.

This interaction brilliantly shows how the devil works, not by force but through temptation to use our flaws against us. In the case of Simba it’s his curiosity.

When Simba arrives at the gorge, Scar again uses Simba’s curiosity against him telling him that his Father has a surprise for him and he must wait on the rock.

Then starts the iconic scene when Scar’s minions start a stampede of wildebeest towards the cub in an attempt to kill him and his Father who has arrived to save him.

Just as the devil tries to turn us against each other, Scar uses Mufasa’s own subjects, the wildebeest, against him and his son.

And as in many biblical stories (such as Moses and Joseph), the hero Simba leaves his kingdom and wanders into the desert and the future.

Years later, the now-adult Simba meets Rafiki again.

Longing to see his Father, Simba follows Rafiki into a maze of thick vegetation.

Finding a pool, Rafiki tells Simba his Father is below the surface, but as Simba looks into the water all he sees is his reflection.

As he looks more intently at his own reflection he begins to see his father’s face. In a poignant moment the clouds gather and Mufasa appears to give his son some words of wisdom.

Like Simba, we yearn to see God in our own lives, especially those moments where we feel lost or spiritually dry.

What is represented here is the knowledge that deep within ourselves, through the maze of our pain, weaknesses and doubt, is the reflection of God the Father in whose likeness we are created.

No matter how lost we feel or how far from God we think we are, we can make a dwelling place for God within our hearts.

God’s appearance to Simba in the clouds is redolent of other biblical scenes such as when Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai and when the disciples witness Christ’s transfiguration.

In this symbolically obvious moment, Mufasa represents God the Father again as speaks to his son Simba who can be interpreted as Christ or us in this scene.

During the dialogue between Father and son, Mufasa tells Simba that he has forgotten him.

When Simba responds with “No. How could I?” Mufasa tells Simba he has forgotten who he is and so have forgotten his father.

The exchange reveals much about ourselves as children of God. When we do not centre our lives on God, the Father, we lose our way and forget who we truly are.

The moment is even more evident when Mufasa tells Simba “You are more than what you have become … You are my son and the one true king. Remember who you are.”

Like Simba, God is calling us to become what He created us to become. We are not made for this world but for a heavenly kingdom.

This particular dialogue also recalls, in some ways, God’s identification of His Son at Christ’s baptism: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Matt 3: 17).

Like Christ returning after His Resurrection to destroy death and bring salvation, Simba returns to the now desolate Pridelands to overthrow his uncle Scar and restore peace and order to his kingdom.

This movie is appropriate for all the family except the very young, who may well be frightened by the malignant figure of Scar and the nail-biting tension surrounding his attempts to do away with his enemies.