Writing about another man’s life saved Paul’s own

Unemployed, unpublished and unable to survive without alcohol, Paul Greguric thought he was at the end of the road. Losing the sight in his right eye in an unprovoked attack in a Sydney pub didn’t stop him from seeing the dark future that lay ahead…or so he thought.

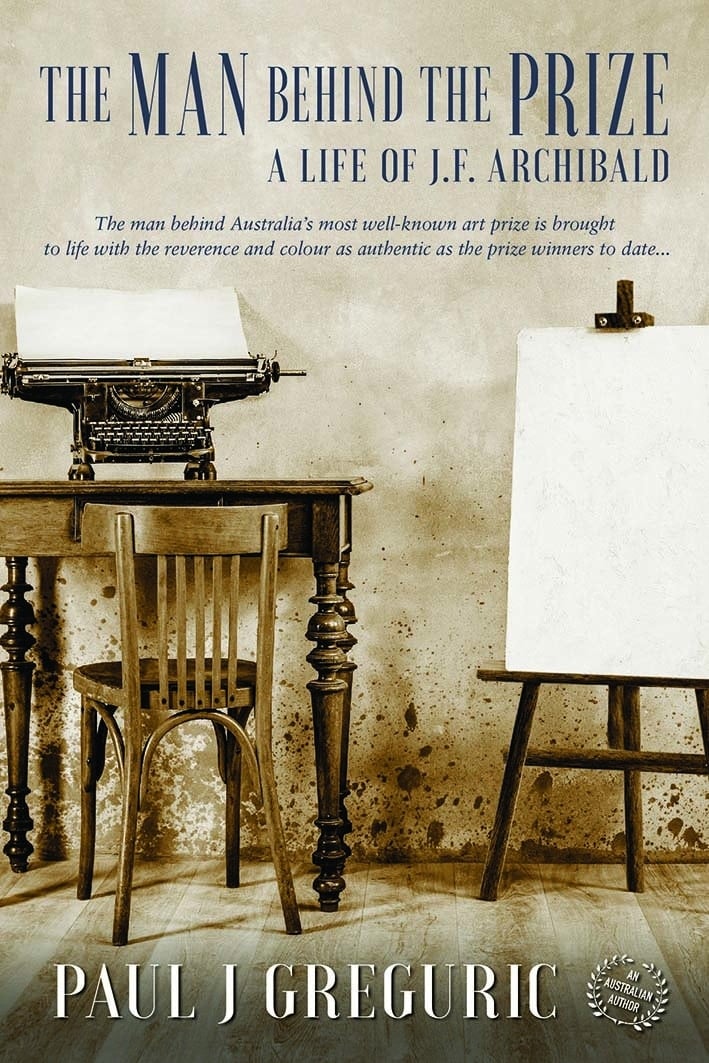

While “living” at the Matthew Talbot Hostel, he developed a relationship with the State Library of NSW and next week sees the release of his first book, The Man Behind the Prize, a life of J. F. Archibald.

Bringing to life the story of the man responsible for Australia’s best-known and most prestigious portrait prize, also saved his own.

Every day Paul would spend hours sitting at the library escaping the chaos and clutter of one of the most well recognised homeless shelters for men around the Sydney CBD, all while forging friendships that would become invaluable when writing his own book.

He can’t help but think the book’s release this month, which coincidentally coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Archibald Prize, may have been helped by a little divine intervention.

“People who have had a near-death situation, like me being badly assaulted, tend to think the fact that they survived means there must be some reason for them being on the planet,” he said.

“And I think my reason was to write the biography of J. F. Archibald.”

The start of a nightmare

The retired Catholic high school English teacher’s nightmare began while watching the New Year’s Eve fireworks in a Sydney pub in 2010. Sitting with friends, a man walked in and bashed him in the face with a baseball bat, leaving him with horrendous injuries including the loss of the sight in one eye. Hospital records show he was lucky to have survived suffering a “traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage, multiple facial fractures and rupture of the right globe”.

He took a year off work to recover. Although he stopped working, his medical bills didn’t and a lengthy compensation battle with the NSW Government ensued. After 12 months of rehabilitation, he returned to work in 2012 and after three years in the classroom decided to resign and fulfil his lifelong passion and become a full-time writer.

Having had short stories published in some of Australia’s leading literary journals for more than 20 years, he decided to take a real leap of faith. Smiling, he said he remembers coming across Fiona McCallum, one of Australia’s best-selling authors, who said to him at the time “it took me nine years to see my first pay cheque from writing.” He knew he had his work cut out.

He rented a small house in western Sydney with a family member and spent the next 12 months writing a novel entitled Farasha, (‘butterfly’ in Arabic) depicting his colourful suburb of Liverpool. After repeated unsuccessful attempts to get the book published, he returned to his hometown of Adelaide to spend some time with his mother.

Suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from the attack he slipped into using alcohol as a crutch. His doctor suggested he take a couple of months off, which he did in Thailand, where his late wife was born and he could speak the language.

Arriving in Bangkok, a member of his wife’s family bumped into him on the street and invited him to stay with them on their rice farm in the Isan region, a very poor part of north eastern Thailand.

“People who have had a near-death situation, like me being badly assaulted, tend to think the fact that they survived means there must be some reason for them being on the planet,” he said.

Resident at the Matthew Talbot Hostel

Despite struggling to make their own ends meet, they hosted Paul while he healed. Returning to Sydney with nowhere to live, he fell back into heavy drinking and turned up at the Matthew Talbot Hostel. He still remembers the exact date – 20 August 2017.

With everything he owned in one leather suitcase, he was given a bed in G Dorm with about 50 other ‘brothers’ as residents refer to each other. Located in Wolloomooloo, the Hostel, a work of the St Vincent De Paul Society, provides accommodation and specialised support to the homeless or those at risk of homelessness.

Up at 6am, breakfast at 7.15, vacate your room by 9, back for lunch at 12.30, dinner at 5.30 and lights out at 9 – he quickly fell into their routine.

”My first night I felt I was at the end of the road, but I also felt I was in very safe hands,” he said. “When you first get to the Talbot you can’t see any way out, you realise you are at the very bottom of the social strata.

“However, it’s the Talbot staff who give you your dignity back in small ways. I remember my first night I felt safe and that the men called each other ‘brother’. The staff treated us with respect and we were well fed and clothed, and the nurses in the clinic looked after me.

“When I arrived I had difficulty walking – one of the symptoms of my alcohol withdrawal. Coming here was not just a bed, it was a dry base. I spent every day at the library, working on a book called Angel in Disguise about living on a rice farm in Thailand, but couldn’t get it published so I abandoned it.”

While not an easy road, almost a year to the day he checked in, Paul checked out of the hostel and moved into a private boarding house. Looking back on his time at the Talbot, he said the one thing that surprised him most was how important going to Mass was for the men.

“I was astonished that all of the men in the chapel wanted to hear the Gospel and receive Holy Communion, no one was making them go, these guys just wanted to go,” he said. “I think it’s because to homeless men Christianity and the Gospels are very relevant.

Sustained by attending Mass

“Even though I’ve moved out of the Talbot, to this day I still go to Mass there every Sunday for three reasons: firstly to have Holy Communion, secondly to hear the Gospel and thirdly to be with my brothers … in that order.”

Once settled into his new accommodation, he very quickly fell back into his old habits…one of them his daily visit to the library. Passing the Art Gallery of NSW each day, he remembers seeing banners about the Archibald Prize and was intrigued. Who was this man who bequeathed funds to have the Archibald Fountain built in Hyde Park and established Australia’s oldest and most-loved art prize, anticipated and viewed annually by thousands?

He did some research and to his astonishment found very little about the man who also started one of the nation’s most iconic newspapers, The Bulletin, and nurtured the careers of Australian writers and artists from Miles Franklin and Banjo Patterson to Norman Lindsay and Florence Rodway.

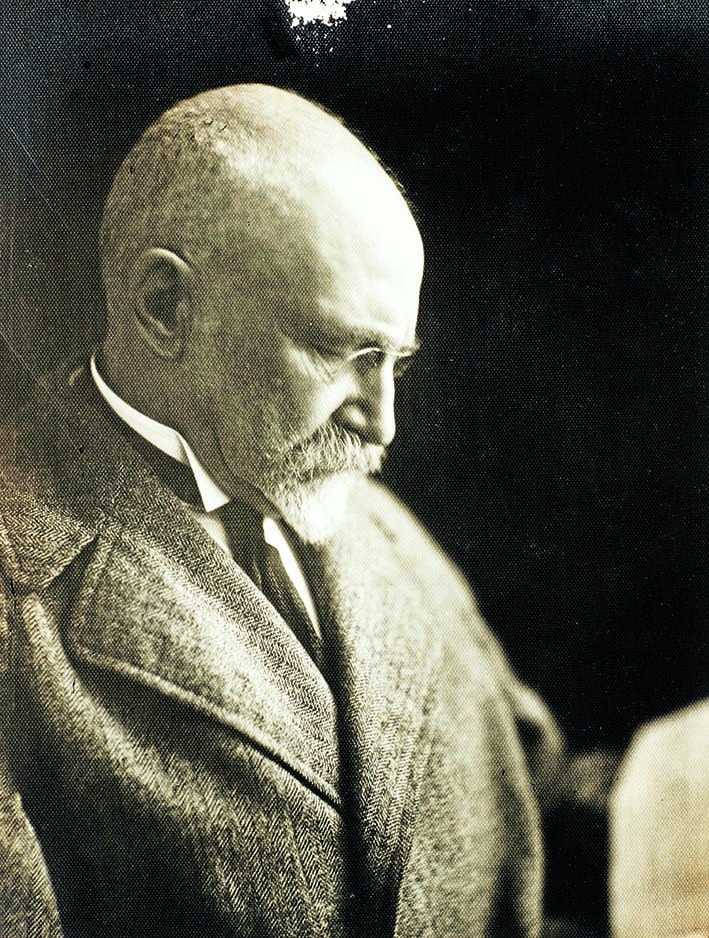

According to the Art Gallery of NSW website, John Feltham Archibald (1856-1919) was a journalist, who also served as a trustee of the Gallery. “He is the man behind one of Australia’s oldest and best known art prizes for portraiture. Yet Archibald had no desire to become famous and, during his lifetime, shunned publicity and remained evasive and enigmatic,” reads a short statement on the site.

The next day, Paul arrived at the Library and began writing. Something that happened that day left him without a doubt that he was on the right path. Living on unemployment benefits and with $14 a day to live on, life was tough and every cent counted.

A good samaritan, who today remains anonymous, stepped in and made what most would see as a basic gesture, something he couldn’t put a price on.

“For the duration of the book, which was about 18 months, I didn’t buy a coffee and to this day I still don’t know who my Guardian Angel was.

“Every morning on my way to the library I would stop at the Sydney Hospital Café and order a coffee, $3.50 might be nothing to most people but when you are living on $14 a day it’s a big whack,” he said.

“The first day I walked in and paid for my coffee, the next day I ordered the same thing and when I went to pay, the manager said ‘your Guardian Angel has come in and will pay for your coffees from now on’. For the duration of the book, which was about 18 months, I didn’t buy a coffee and to this day I still don’t know who my Guardian Angel was.

“Writing the book was something I had to do and this just confirmed that. No-one had written about him since the 1980s when the late Sylvia Lawson wrote a book called The Archibald Paradox, now out of print.

“When I began researching, I thought there was nothing there but after finding one hand-written card in an old timber catalogue case written by his half-sister, I knew I would be able to write the book.

“I accessed letters, journals, newspaper articles, photographs, notes and jottings which proved invaluable.”

Looking back on his life, Paul’s faith has become a daily part of his routine and he starts every day by inviting Jesus into his. He is adamant he will never end up back at the Matthew Talbot, partly because “there are men that need it more than I do”.

“I ended up at the Talbot having pretty much destroyed my life through alcohol and was surrounded by men who had pretty much done the same, whether it was due to alcohol, drugs or even mental health issues,” he said.

“I’m not ashamed of my past but pretty chuffed when someone asks what I do for a living and for the first time I can say author.

“Life is still not easy and I take each day at a time. While I have seen a lot of pain, if my life had gone in the other direction I would be in my 30th year of high school teaching and I would never have written this book.

“I’m thankful.”

The Man Behind the Prize, a life of J. F. Archibald can be ordered online at https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-man-behind-the-prize-paul-j-greguric/book/9781922444622.html