Several prominent Catholic leaders have been charged, tried and convicted in calculated efforts to destroy their leadership

By Tony Macken

In the 100 year period between 1850 and 1950 three Catholic churchmen of international reputation were assailed by the full power of the State.

In one case, the intended victim was an English convert priest, in another a fearless German bishop and in the third a distinguished Hungarian cardinal.

The regimes which sought to discredit them could not have been more dissimilar: the Establishment of Queen Victoria’s England, the Nazis of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s satellite regime in Soviet-occupied Hungary.

In all cases bitterly anti-Catholic persecutors singled out public figures chosen for their unashamed defence of Catholicism, seeking to isolate and discredit them as leaders of their community.

The attempt failed in each case and the intended victims survived the ordeal to which they were submitted.

All three were, or became, cardinals of the Catholic Church. They were John Henry Cardinal Newman, Clemens August Cardinal von Galen and Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty.

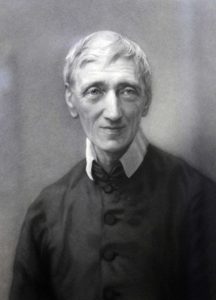

John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (born 1801, died 1890) was made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church in 1879 when aged 78 in one of the first acts of the new Pope Leo XIII. Newman was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in Birmingham, UK, on 19 September 2010.

For students of English literature, Newman is an acknowledged master of English prose, notably expressed in the passionate defence of his own character against attacks by Professor Charles Kingsley, originally published by Kingsley in the Macmillan’s Magazine of 30 December 1863.

Kingsley published his polemic as “CK” but was at the time Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge and a successful novelist whose works included Westward Ho! (1855), and The Water-Babies (1863). Newman’s refutation of Kingsley’s attack was initially published as a pamphlet on 12 February 1864.

This was reviewed in a two-part article in The Spectator by its literary editor Richard Holt Hutton under the title ‘Father Newman’s Sarcasm’, describing Newman as “not only one of the greatest of English writers, but, perhaps the very greatest master of delicate and polished sarcasm in the English language”.

Controversy

Kingsley returned to the attack on 20 March 1864 with a pamphlet ‘What, then, does Dr Newman mean?’

Newman’s devastating reply was published in ultimately eight parts collected as a single volume in 1864 under the title ‘Apologia pro Vita Sua: Being a Reply to a Pamphlet entitled ‘What, Then, Does Dr Newman Mean?’

A second edition which appeared in 1865 was entitled ‘History of My Religious Opinions’ and a third published in 1873 returned to the original title with a subtitle ‘Being a History of his Religious Opinions’.

If the Apologia was Newman’s literary masterpiece, his most immediate service to the Catholic section of English society in retrospect was his trial and conviction for the serious offence of criminal libel.

On trial

Newman had been received into the Catholic Church on 9 October 1845 and by 1850 was serving as an ordinary Catholic priest. In July 1850 Cardinal Wiseman had published in The Dublin Review a scathing denunciation of an apostate Italian priest, Dr Giacinto Achilli, as a profligate and seducer then making a lecture tour of England denouncing the Roman Catholic Church.

Newman relied on Cardinal Wiseman’s text and publicly repeated Wiseman’s charges which had not been responded to by Achilli.

The charges against Achilli were true: but Achilli’s backers, well advised, brought proceedings for criminal libel and the allotted hearing dates and procedures of the Court meant that Newman was not able to call evidence from overseas in time to establish in Court (as acquittal required) the truth of the allegations he had repeated against Achilli. A jury trial presided over by Lord Campbell began on 21 June and ended on 29 June 1852.

Conviction

Newman was convicted and finally sentenced on January 31, 1853 to payment of a fine of 100 pounds and what was confidently assumed by his critics would be Newman’s social disgrace and isolation.

Aspects of the conduct of the trial by the presiding Judge were widely criticised, earning a leader in The Times which commented that Roman Catholics could no longer have faith in British justice.

The costs of the defence and the expense of bringing witnesses to England amounted to 12,000 pounds, a colossal sum, which was quickly raised by public subscription.

The prosecution of John Henry Newman and its aftermath earned for Newman sympathy due to a man in public life perceived by the public of the day to have been unfairly dealt with.

The adverse public reaction disturbed the unthinking anti-Catholic bigotry of the day expressed in the populist slogan “No Popery”.

It also created out of what had been a diffuse and divided party the beginning of a community in England with a greater sense of its Catholic identity and proper place in the public square than would have been imaginable before Newman’s prosecution and conviction.

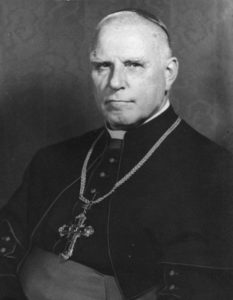

Clemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens August Graf von Galen (born 16 March 1878, died 22 March 1946) was made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church on 21 February 1946 when aged 67 in one of the first post-war acts of Pope Pius XII. He was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI on 9 October 2005 in St Peter’s Square.

Von Galen was the Bishop of Munster, a German nationalist and an outspoken public critic of Nazi practices, particularly the practice of euthanasia which he condemned in outspoken terms. Nazi racial doctrines he dismissed as ridiculous.

While priests, students and others who distributed his sermons denouncing the Nazi regime were, if detected, imprisoned or in three cases executed, Von Galen’s personal authority and following made him generally untouchable other than by house arrest and harassment and a period of detention in Sachsenhausen concentration camp where an estimated 30,000 prisoners died.

Targeted by Hitler

Hitler, however, in table-talk declared Von Galen would not survive a Nazi victory: “I am quite sure that a man like Bishop von Galen knows full well that after the war I shall extract retribution to the last farthing,” the Fuehrer said.

Von Galen’s powerful sermon condemning the Nazi practice of euthanasia was delivered on 3 August 1941. It has been described as the most important and the most outspoken sermon delivered by a member of the Catholic hierarchy during the Nazi era.

The Nazi regime had formally initiated its euthanasia program in 1939 under the code name Aktion T4, and with the purpose to eliminate “life unworthy of life”.

Denunciation from the pulpit

Von Galen denounced this system in a sermon delivered on Sunday August 3 1941 in Munster Cathedral. It immediately caused consternation at the highest levels of the Reich and triggered an outbreak of civil disobedience.

“If the principle that man is entitled to kill his unproductive fellow-man is established and applied,” von Galen told his congregation on 3 August 1941, “then woe betide all of us when we become aged and infirm!”

“If it is legitimate to kill unproductive members of the community, woe betide the disabled who have sacrificed their health or their limbs in the productive process!

“If unproductive men and women can be disposed of by violent means, woe betide our brave soldiers who return home with major disabilities, as cripples, as invalids!

“If it is once admitted that men have the right to kill ‘unproductive’ fellow men – even though it is at present applied only to poor and defenceless mentally ill patients – then the way is open for the murder of all unproductive men and women; the incurably ill, those disabled in industry or war. The way is open, indeed, for the murder of all of us when we become old and infirm and therefore unproductive …

“Then no man will be safe: some committee or other will be able to put him on the list of “unproductive” persons who in their judgment have become ‘unworthy to live’. And there will be no police to protect him, no court to avenge his murder and bring his murderers to justice … Who could then have any confidence in a doctor? He might report a patient as unproductive and then be given instructions to kill him.” ….

Euthanasia goes into hiding

As a result of von Galen’s sermon, on August 23 1941 Hitler suspended Aktion T4 which had, to that date, accounted for some 73,000 deaths. The program continued in secret at decentralised locations.

Its methodology, its equipment, its skills and even its key Nazi personnel were next transferred to “the final solution of the Jewish question” by the mass murder of Jewish men, women and children transported to Nazi-occupied Poland where voices like that of von Galen could not be heard.

The “slippery slope” from the small beginnings of Aktion T4 in October 1939 to the notorious Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942 at which the Nazis planned the ‘Final Solution’ of the Jews of Europe, was 28 months.

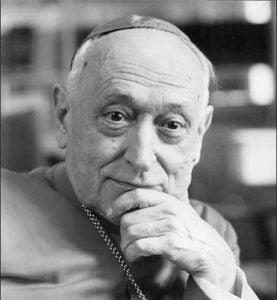

Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty

Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty (born 29 March 1892, died 6 May 1975 aged 83) was made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church in February 1946 by Pope Pius XII, a few days before his German contemporary Cardinal von Galen.

Arrested by Fascists on 27 November 1944 for his opposition to the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross regime, Mindszenty was released from home arrest on its collapse in April 1945.

On 23 December 1948 he was arrested and charged with treason and conspiracy by the Soviet puppet regime in Hungary.

The charges were widely viewed outside Communist Hungary as ridiculous and unbelievable and included a plot to steal and sell the Crown of St Stephen, a national treasure, to finance a US-backed takeover.

Tortured and drugged

Tortured, drugged, submitted to a show trial commencing 3 February 1949, and concluding five days later on 8 February with a sentence of life imprisonment for treason, Mindszenty’s trial was filmed and evoked revulsion throughout world media and at the UN.

On 12 February 1949 Pope Pius XII excommunicated all persons involved in the trial and conviction of Mindszenty.

The Cardinal remained a prisoner of the regime until the short-lived liberation of Hungary in 1956 when he was granted sanctuary in the US Embassy, remaining there for 15 years until allowed and pressured to leave Hungary in 1971.

Trial focuses the world

Cardinal Mindszenty’s trial and conviction projected Catholicism worldwide as a central actor in the world struggle against Soviet Communism and its satellite regimes which continued until their dispersion in 1989.

Up until Mindszenty’s trial in 1949, the goodwill earned by Stalin’s regime for Russia’s role in the second world war still influenced the minds of many Western intellectuals.

Mindszenty’s trial showed the true face of Soviet Communism to many and played a part in the world-wide mobilisation of public opinion against Stalin’s regime and the adoption by the West of the ultimately successful policy of containment.

After the fall of the Soviet Empire in 1989 Cardinal Mindszenty was taken home to Hungary and buried in 1991 in the Basilica at Esztergom, northern Hungary, the seat of the Hungarian Catholic Church, honoured by all.

Tony Macken is an Australian Catholic layman and Catholic Weekly contributor.