The idea of equality before the law has its origins in St Paul’s Letter to the Galatians (3:28): “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, given you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

This is the ultimate Christian statement of the inherent dignity of each person, and implementing this ideal over the last two centuries has been the great calling of the Western liberal democratic tradition.

These considerations are critical when it comes to the debate surrounding the referendum on the proposed constitutional change to include an Indigenous Voice to parliament and executive.

Many eminent members of the legal profession, in practice and in academia, along with former High Court and Supreme Court judges, have lined up to strongly support the “No” case.

Their contributions highlight, among other things, that a constitutionally enshrined body defined by race, which only Indigenous Australians can vote for or serve in, is inconsistent with the fundamental principle that all citizens are to be treated equally. Such an eventuality would be the first in any liberal democracy.

The liberal democratic tradition has historically placed freedom of the individual at the center of our concerns, opposed collectivist ideas—not only of class but also race and gender—and has shown us why central planning is destructive of liberty, and why it does not and cannot ever work.

One person who understood this better than most was St John Paul II. As one who lived under communism, he saw how destructive a force it was, particularly in terms of its effect on the inherent dignity of each of us, created in God’s image.

Hence, he had no time at all for two of Marxism’s ideological children, namely, liberation theology and identity politics.

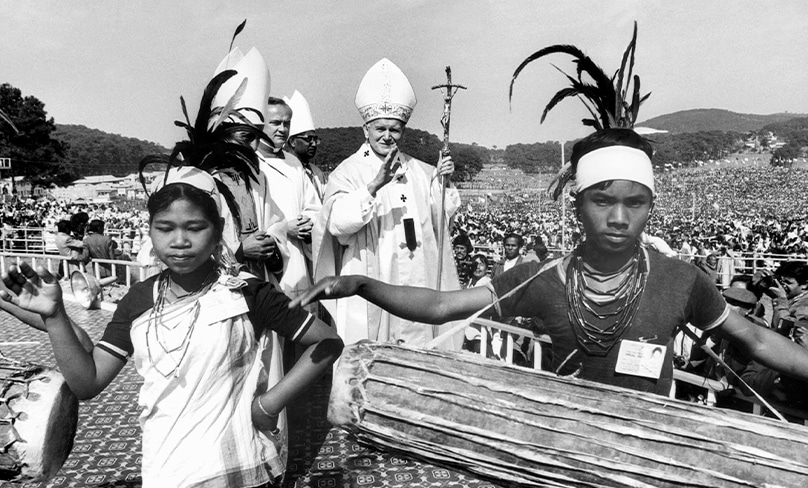

Many readers would recall fondly Papa Wojtyla’s visit to Australia in 1986. During that visit, he addressed Aboriginal people at Blatherskite Park, Alice Springs, calling on all Australians to seek “a just and proper settlement” on the Indigenous affairs question.

However, he added a note of caution: “The establishment of a new society for Aboriginal people cannot go forward without just and mutually recognised agreements with regard to these human problems, even though their causes lie in the past,” he said.

“The greatest value to be achieved by such agreements, which must be implemented without causing new injustices, is respect for the dignity and growth of the human person […] You are part of Australia and Australia is part of you.”

Over the last 36 years since that exhortation was given, Australians have heeded St John Paul II’s call. Indeed, there are 11 members of Aboriginal descent in the Commonwealth Parliament, which is the voice for all of us.

Aborigines are part of the wider political system, and have been for several generations. Moreover, as St John Paul II stated all those years ago, Aboriginal people should reject the idea that they are perpetual victims forever in need of special measures, declaring:

“You, the Aboriginal people of this country and its cities, must show that you are actively working for your own dignity of life. On your part, you must show that you too can walk tall and command the respect which every human being expects to receive from the rest of the human family.”

In other words, he understood that the key to helping the minority of Aborigines who have not adjusted to life in a liberal modern society is to end the obsession with identity, since that is what is causing the most harm.

Nyunggai Warren Mundine, the head of the “No” campaign, and himself a Catholic, is just one example among the majority of Aboriginal people who have done well, without a Voice to Parliament or specific Aboriginal policies and programs.

He told a recent Institute of Public Affairs forum on the Voice:

“For the last 50 years—56 years since the 1967 Referendum—the journey was about equality for all, about equality for opportunities. You cannot make people equal but you can open up opportunities for people and they can grasp those opportunities or not, and that is all you can do in a society […]

“This is the future. This is how you break down poverty. You give someone a job; you get investment on Indigenous lands where they can build businesses and they can do things.”

This is a positive vision for Australia, one in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders reach their full potential in a country that is united, not divided, and one that has as its central tenet, not identity, but, in the words of St John Paul II, respect for the dignity and growth of the human person.