Infinite Regress by Joshua Hren

Published by Angelico Press

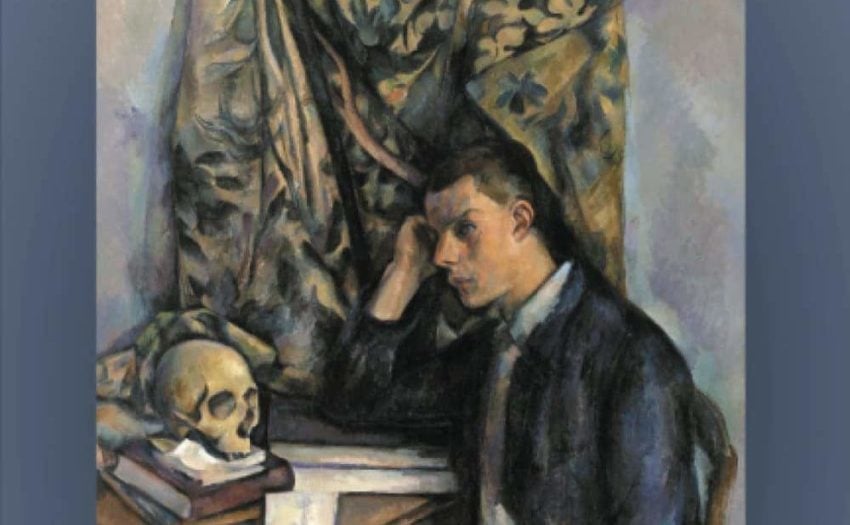

Joshua Hren’s first novel, Infinite Regress, is an ornate saga of a declining family in the declining American Empire.

After graduating college, Blake Yourrick works a series of dead-end jobs in a futile effort to pay off student loans that he barely understands, when his old professor, Hape, a defrocked Jesuit, makes him an indecent proposal in exchange for paying off his loans.

While Blake is the will-he or won’t-he agent of the novel’s first half, Infinite Regress is almost as much the story of his father Garrett, himself even more financially indebted than Blake, a failed academic with too much intellectual integrity for his own good (and the good of his family), slowly drinking his life away.

Garrett is the archetypal modern atheist, paralysed by thought, tragically unable or unwilling to escape the prison of his own brilliant mind, unable to holistically participate in the world.

Blake’s older brother Max, a successful psychotherapist, and his pious younger sister Dymphna, add balance to the family where they can. Blake’s dead mother’s Catholic piety haunts the Yourrick men, none of whom practice, all of whom ponder the mysteries in times of extremis, leaving a tiny room in their hearts open to the possibility of God.

As a writer, Hren has maximalist tendencies (no Flannery O’Connor exacto knives here), reminiscent of Saul Bellow, who chronicled the urban upheavals of 20th century Chicago.

The Yourrick’s Milwaukee is a smaller canvas, yet Hren excels at the verisimilitude of urban life, the chance encounters, the petty frictions. Like Bellow’s Charlie Citrine and Artur Sammler, Hren’s characters are transfixed by charismatic friends and teachers, paralysed with indecision, wracked by regret, determined to chart their own course by their own lights, clinging to their personal integrity like life-buoys in a squall.

Hren shares with Bellow an unusual, and in both cases salutary, obsession with the realities of modern finance. While most literary characters seem to exist in a world where the getting and spending of money aren’t necessary, the emotional vicissitudes of indebtedness, the phantoms it inspires in the mind, the despair, hope and glimmers of freedom experienced by victims of modern usury are here front and centre.

The overarching philosophical tale told in Infinite Regress really starts to hum when we see Professor Hape orating in full flight at a private bar for intellectuals:

“You think Christianity is on the way out? Well, well — have you forgotten that it speaks to our deepest delusions, our most pathetic ‘needs’? … we can’t rid the world of theology, and so we need to rewrite the terms of the debate … what we need to reinterpret is …Satan and his state.”

Hape is no naïve atheist, but a pernicious theorist of good and evil, far more dangerous to faith and the Church than someone like Garrett. The book contains several spectacular set-pieces: Hape’s parable of Satan at the first auto-de-fe, Blake’s philosophical riff on the idea of “repossessing your education” that gets him fired from his job at a student debt-collecting call centre, and probably the funniest police report ever put to print.

At 285 tightly-spaced tall pages, Infinite Regress is not always a leisurely read. Hren treads the line between exhausting or exhilarating the reader.

His is a daring style that says something all on its own about the blended, baroque nature of life, evoking that sense of the-bottom-falling-out, that “infinite jest” at the centre of the void of contemporary life without God.

The text itself rushes up at the reader without chapter breaks, just long sections separated by the infinity symbol, towards a frenetic but thematically satisfying ending, where the truth of the fully integrated God-bearing mind, body and soul of man is revealed.

Infinite Regress lives up to Hren’s own words in his artistic manifesto Contemplative Realism: “contemplative realism registers the supernatural as harmonious with the natural.”

In Infinite Regress, the Almighty’s presence is felt not as crude deus ex machina, but as slow, patient, reordering and setting right, stage-setting, allowing the characters to see for themselves.

Usually a novelist’s explicit theoretical musings come late in a career. Hren has run a huge risk here being a practitioner after being a theorist, but like Babe Ruth calling his shot or Joe Namath guaranteeing victory in Super Bowl III, bravado has a way of focussing the mind.

Infinite Regress is easily the best Catholic novel since Beha’s What Happened to Sophie Wilder. We few, we happy few, who follow the world of Catholic fiction like it’s a major league championship, welcome a new frontrunner.

Lucas Smith is a poet and writer from Melbourne. His work has appeared in Australian Poetry Journal, Meanjin, Southerly, Dappled Things and many other journals. He is Editor in Chief at Bonfire Books.