Concentrating on the plight of individuals can prove more successful in outlining human sufferings than presenting the way tragic events are affecting many thousands of people.

Media professionals have long observed and put this into practise in covering the way grim situations impact on one person rather than numerous others.

A strong case was demonstrated last month in relation to the refugee crisis engulfing the people of Syria.

Many of them had tried unsuccessfully to seek transport to safer places. Widespread coverage was devoted to those distressing attempts but it was the image of the dead body of one small boy being carried along the seashore that made the greatest impact and provoked readjustments to the hard-line policies of several countries, including those of Australia.

Three-year-old Aylan Kurdi’s family had fled Kobane and had been attempting to travel to Greece, but the boy drowned along with his mother, Rehan, and five-year-old brother, Galip.

Despite debate over the cirumstances surrounding his death, the heartstrings of people around the world were tugged more strongly by that image rather than from vision they had seen of numerous other lives desperately trying to board trains or buses to comparative safety.

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is a line often uttered regarding the coverage of news stories, but some pictures can be worth more words than others.

When a young child is seen as paying the ultimate price for simply being amid a conflict in the Middle East, it shows the tragic outcome of human suffering that is affecting much larger groups of people.

One local television host cried on air while she reviewed coverage of that death on the beach.

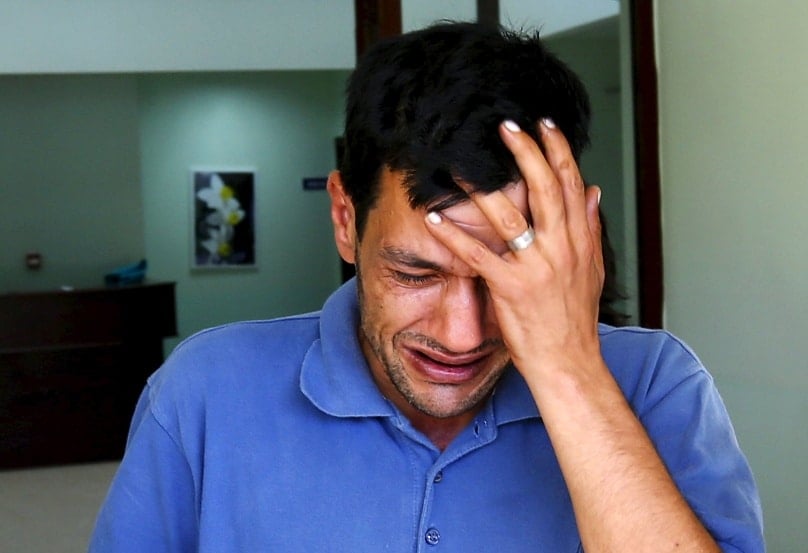

A later interview by an Australian television crew also brought home the personal side when 62-year-old Nazieh Abul Rahman Husein, who had lost his wife, daughter and son revealed: “I wish to see them again. This is my only wish in life.”

These stories effectively twigged a broader realisation that refugees are people like us having their hopes and dreams dashed.

The media coverage given to that dead boy had an impact more powerful and more far-reaching than scenes from crowded rail terminals where numbers seemed to make handling the refugee

problem overwhelming for many.

Perhaps that explains why TV news at times has placed short clips about tragedies in foreign lands somewhere amid a montage of overseas stories well into their programs, before then presenting

lighter incidents or promoting upcoming sports reports.

Criticising the news media can be justified, but those who are charged with reporting national and international events do exhibit a good understanding of aspects of human nature. They realise that individual rather than group coverage can produce strong impacts – such as the coverage afforded to that dead boy on the beach.

Hard line attitudes to the entire refugee problem from those who had considered it was satisfactorily addressed because Australia had “stopped the boats” were shaken.

Changed public opinion put increasing numbers of people at odds with the stance of radio “shock jocks” and a government that had stopped the boats but had obviously failed to fix the refugee problem.

Australia agreed to take an additional 12,000 Syrian refugees only a couple of weeks before the statement by the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference on Social Justice Sunday last week which said that stopping the boats had merely shifted the problem somewhere else.

“Our neighbour is the person before us in need. Those kept faceless and nameless behind the veil of border security operations are now revealed to be our brothers and sisters – the mother and child fleeing war, the father desperate to secure a future for his family,” the bishops told us.

When those additional refugees reach our shores later this year, they will owe much to reactions stirred by the loss of that one small child.

Our nation will be delivering on the gospel words of Christ: “Anyone who welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me.” (Mark 9:36)