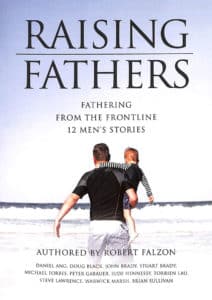

In Raising Fathers, I was privileged to share the story of my paternal grandfather Lian Kooi and of my father Keong Heng Ang, both born in Malaysia of Chinese descent, and the impact that this ancestry had upon my own life and now that of our family.

Origins

My grandfather was born in Johore, in the south of Malaya, in 1912, broad and heavy-set though only 5’3” tall. With thick black hair combed back from a wide and intimidating face, he could look severe.

However, despite this appearance he was in character a social man, so outgoing that my father barely remembers him being home.

My grandfather earned his keep selling linen and crockery to miners who had flocked to the north of Malaysia, to the town of Taiping.

Meaning ‘everlasting peace’, the quiet of Taiping was shattered by the Japanese invasion of then-Malaya in December 1941, just a few short hours before the bombing of Pearl Harbour.

As the Japanese Imperial Army moved south, the family fled, desperate to escape the horrors that were to be inflicted on the men, women and children throughout the occupation.

Like hundreds of others in Taiping, my grandfather fled to the relative safety of the surrounding jungle. Lian Kooi and my grandmother Lai Fong were among the hundreds of fleeing villagers and, fearing the advancing Japanese army, the young family friends were hastily married in the hope to protect Lai Fong from the threat of capture and exploitation. Eventually separated by the invading forces in 1944, my grandfather would endure torture at the hands of his captors while my grandmother was imprisoned with her newborn son, my father, before the war came to its welcome end.

Eventually separated by the invading forces in 1944, my grandfather would endure torture at the hands of his captors while my grandmother was imprisoned with her newborn son

Home Away from Home

In the years that followed, the Ang family grew to a total of 11 with eight more children born in quick succession. However, as time went on Lian Kooi was rarely seen at home. It is sadly one of my grandfather’s legacies that he was conspicuous by his absence.

At night, Lian Kooi, Lai Fong and eight of the children would sleep in the only bedroom while my father took to sleeping alone in the corridor on a fold-up canvas bed. Even in these early days, my Dad’s place within the family was as one set apart rather than one at home within.

My grandfather worked various jobs with mixed success as a salesman and then a store owner and finally as a taxi driver. It was this last enterprise that would eventually cost him his life. When my grandfather died in a car accident, my father was already living in London, having moved there to escape small town Taiping, to work as a nurse and in time bring my mother over who he had met at the age of 17. My father had met my mother, Kah Chin Chong, at a Gospel Dance Hall at a dance in 1964 celebrating the leap year and before long they were both working as nurses in London at an institute for adults with learning disabilities. They were married in that city where my older brother Desmond was born.

My father does not speak of his own father very often. There is no hint of resentment or nostalgia for lost days, however, only the facts. The ultimate legacy of this upbringing and these events on my father was a keen sense of self-reliance and responsibility for his eight siblings, a widowed mother and for his own uncertain future.

His entrepreneurship was not the product of choice but of circumstance. Whether it was catching fighting fish to sell at market or collecting leftover copper wire from building sites in Taiping, or selling ice creams from a van between hospital shifts in London, his industriousness and creativity were a necessity, not a luxury. These were traits sorely lacking in his own father from whom it seems my father inherited very little, not only materially but by way of example.

Over the years I have only grown in admiration of my father’s independence and capacity for hard work because it has opened a world of possibility for us and for others, his many brothers and sisters included. I have no doubt that this role as provider and shepherd of the family came at some personal cost, for he was inevitably seen by his brothers and sisters less as a sibling and more as a father figure whom they feared as much as they respected. This was also my experience as my father’s son, and the economic pressures and severe discipline within our home led to some estrangement of my brother and I from our parents and even from each other. With no bond as it were at the centre of our family, years of dissolute living followed which continued well into my years at university with impacts on my health and relationships. Once I had peered over the edge of life, almost to see how far one could fall, the insufficiency of this lifestyle led me to seek out the Gospel and on the eve of the new millennium to embrace the Catholic faith.

This journey to baptism as a then 20-year-old was difficult as it demanded a turn towards a new path that again differed from family expectation and a turn away from illusions of self-sufficiency and misplaced desire.

With the relationship with my father and mother strained at the time, I struggled to find even the most basic words to tell them of my decision to be baptised and when I did, on its eve, they fell out with awkwardness and insecurity. My father, as was his tendency, did not utter a word while my mother reacted with slight surprise and gently inquired when it was all going to take place.

I still wish I could have explained myself better. I was grateful for the small group of friends and sponsors that gathered for my baptism that drizzly Wednesday night on 24 November 1999. I took the Christian name ‘Matthew’ because he was a disciple not in spite of, but because of, his being a sinner.

In time I was married in the church of my baptism, to my wife Sara who also entered the Catholic Church as an adult. In the years that followed I worked in media and advertising before taking up my first Christian employment with the Daughters of St Paul and seven years later with the Diocese of Parramatta, in Sydney’s west. I am now privileged to serve here in the Archdiocese of Sydney.

Reflecting on who I have sought to be for my son and daughter as a father, I have been striving above all to ensure that they take confidence in my presence and love. Standing on the shoulders of my own father, I am able to offer our children more time and attention than perhaps past generations. Like my father, I am striving to provide for their material needs but distinctly also offer a witness to the ordinary, often understated joys of Christian living before they inevitably encounter life’s suffering and self-emptying demands. I try to teach my son in an emotive and often wayward world how to live or act not merely by feelings but by what we value, and about joy, not as getting what we want but as the experience of being loved. We speak about the Gospel and the Christian origins of and influences on the great stories of our culture, the reality of being distinctive as Christians in a complex world, and they ask simple and deep questions with a trust that I seek to honour as best I can.

My prayers as a father are of course for their present and their future, for our family as a whole, for my own mother and my father who is unwell. In the past years my father and I have grown in intimacy and through the inevitable ups and downs of relationship we have emerged closer than ever.

Reflecting on who I have sought to be for my son and daughter as a father, I have been striving above all to ensure that they take confidence in my presence and love.

As my Dad gets older, I know I will someday miss him terribly and I have enough perspective to enjoy the moments and the time that remains. This possibility of love, respect and mutual devotion in our relationship has in no small part been enabled by my Christian faith which has opened up a new horizon of appreciation within me for what is good though imperfect, whether that be my father, the life of the Church or my own fatherhood which is still growing and changing in its gifts and demands. At the celebration of my parents’ 50th wedding anniversary a few years ago now, I could share with my father that I love him and that my brother and I, and their circle of friends, have been recipients of fifty years of marriage which has given them more than they could have expected and more than for which we can give thanks. My mother’s care and daily dedication to my father and our family have been paired with the presence of integrity, dedication and love embodied by my father who nurtured our lives and my Christian faith. He has taught me the gift of being a father by being, first of all, a faithful son.

Raising Fathers: Fathering from the Frontline – 12 men’s stories, edited by Robert Falzon, foreword by Greg Craven, Connor Court Publishing, 290 pages is available from The Mustard Seed Bookshop