In the Second Part (of the Second Part) of his Summa Theologiae (question 129), Saint Thomas Aquinas explores an intriguing quality of character he calls “magnanimity” (literally: big-spiritedness). To do this he draws upon the more ancient classical thought of “The Philosopher” – Aristotle, Socrates and Cicero but he also moves beyond them.

St Thomas describes the magnanimous as large hearted, wide-minded, great souled and hugely energetic (and practical) towards “great things.” They are not just naturally gifted – they strive and struggle after the deep, the beautiful and the truly good. Such people inspire and goad those around them to great heights. The magnanimous man is (in Greek) megalokindynos, he expends himself to the point of danger to himself for the things that really matter.

There is nothing of the banal or mediocre about the big-spirited. The great-minded often push us out of our comfort and composure and they can fire darts into our puffed-up illusions.

A big-spirited person is not however the assertive (and ultimately blind-sided) egoist, the person after fame, glamour (magnificence in Thomas’ time) or worldly honours, the petty-minded activist nor yet the nietzschean superman or woman- the fodder of our less than magnanimous buzzfeeds. These are all faux versions of true greatness.

Thomas says the epitome of the magnanimous is paradoxically also the loving and humble Christian whose closeness to grace and to the humus (the earth) enables him or her carry out what seems to the small minded and faint hearted to be impossible.

Christian magnanimity is “the jewel of virtues” and it is not a common trait in any time.

The German philosopher Josef Pieper writes: “particularly in ethical matters— (the great-spirited person) decides in favor of what is, at any given moment, the greater possibility of the human potentiality for being.”

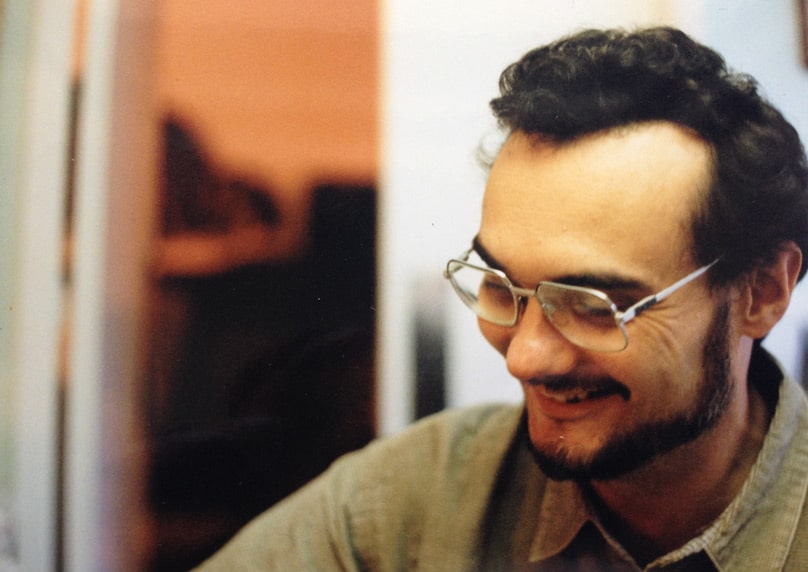

There is one, contemporary Australian person who I believe captures what Thomas calls the “irascible”, the courageous and “chivalrous” quality of Christian large-spiritedness: Professor Nicholas Tonti-Filippini (5 July 1956 – 7 November 2014).

This week marks the third anniversary of the death of this giant-hearted Australian public intellect, philosopher and bioethicist. Shortly after his death, many contributed to an on-line tribute to Nicholas.

I wrote on that page at the time of Nicholas’ astonishing largesse and scale of collaboration with so many: the mighty and the voiceless:

“His personality was hallmarked by a fierce awareness of the unrepeatability of each moment. This gave to his labouring for authentic education and ethical engagement a compelling acuity and focus… Nicholas possessed a restless and rapid-fire intellect with the liberality of Socratic spirit which made him a teacher in the most profound and borderless sense,”

“Nicholas taught, mentored and befriended a vast number of those on the professional and personal ethical quest: midwives, surgeons, politicians, journalists, High court justices, parish counsellors, fertility teachers, grieving parents, prelates and students at all levels – here and overseas – across the philosophical spectrum.”

I realise today that I was reaching for a quality which St Thomas has named over 700 years before: magnanimity.

There was also a fine personal tribute to Nicholas in the pages of The Catholic Weekly by Archbishop Anthony Fisher which captures this quality.

In the middle of this year, Archbishop Fisher launched Nicholas’ last (and posthumous) volume in the: About Bioethics (series) faith, science and the environment

Archbishop Fisher captured the magnanimity of Professor Tonti-Filippini’s impact and inspiration to himself, to Australian society and to the Church even today:

“Nicholas Tonti-Filippini was the most highly regarded voice in Catholic bioethics in Australia of his generation not just amongst Catholics and the media, but also in civil society.”

Reading the Archbishop’s words again this week, I cannot but regret that in so many ways our Australian public policy and discourse has become more petty, vindictive, ad-hominem and mean-spirited since his departure.

We can only imagine how Professor Nicolas might have changed the climate and tone in our debates over gender theory, marriage law, refugee custody and most particularly in the dangerous slide into medically-perpetrated killing.

The John Paul II Institute’s current Bioethics Lecturer and Fellow, Dr Paschal Corby, gives fine voice to Nicholas’ protest against legalised medical killing, reminding us that Nick himself was man who struggled long and hard with debilitating pain and disability but with at the same time a magnanimous and generous moral imagination.

Fr Corby writes: “He was constant in maintaining that the chronically and terminally ill are not helped by the option of euthanasia; that they do not need to be burdened further by implications that their life is not worth living.”

There is one more thing about the quality of magnanimity of which Nicholas Tonti-Filippini was such a rousing example, that this big-spiritedness is meant not just for himself but to be shared in moments of kinship and friendship and in generosity of endeavour.

Magnanimity seeds communio and roundtables. Nicholas was the master of the round-table in ethical discussion between people of diverse philosophies as he was around his family table.

Archbishop Anthony Fisher notes again: “For half my life I had the benefit of Nick’s wisdom as a scholar, his piety as a fellow Christian, and his personal support as a true friend. I have said before that I think such friendships can be our most tangible experience of divine grace; they sustain and enlarge us; they are, in a sense, sacramental.”

It is therefore not surprising that Nicholas’ magnanimous round-tables did not die with him. Today his legacy lives on some important projects that were near to his tireless heart and mind.

One great breakthrough, is the establishment of the Australasian Institute for Restorative Reproductive Medicine (AIRRM) which aims for the first time to bring together research, medical and allied practitioners and the three national Fertility Awareness Agencies (that is Symptothermal Method; Creighton Model FertilityCare System and Billings Ovulation Method) into collaborative partnership. The joint aim is to pursue “excellence in provision of physical, psychological and spiritual care to people experiencing infertility and reproductive health disorders.”

We will be exploring, at The Catholic Weekly, in the coming week, some of ground-breaking issues raised by Third National Fertility Conference last week – which was a direct consequence of Nicholas’ efforts and vision.