Every once in a while, a pro-choicer will try to entrap a pro-lifer with a thought experiment. “Oh, you claim microscopic embryos are human? Well, imagine you’re in an IVF lab that’s on fire, and you only have time to make one rescue before the whole thing burns down. Do you save a crying toddler, or do you rescue a cooler that holds thirty frozen fertilised eggs?”

This is supposed to be an unbeatable trap. If you save the toddler, that proves you think a born child is more real than even 30 fertilised eggs, and since you claimed life begins at conception, that makes you a liar; but if you save the fertilised eggs, which is saving 30 people, that means you’re choosing to let a crying child perish in flames, and that makes you a monster.

Some situations are impossible

Well. I believe that life begins at conception, and I would save the crying child, because people in horrible situations do the best they can, and all it proves is that horrible situations are horrible. We respond to human impulses, and our humanity compels us to rescue the person most present to us.

If a pro-choicer in a similar burning building chose to save his own child instead of a child he’s never met, or a crying child instead of a sleeping child, that wouldn’t prove he thinks the child he doesn’t save is less human; it just shows that some situations are horrible, and we do the best we can. I can simultaneously believe that the fertilised eggs are fully human, and know that I would save the human who was calling to me for help. It’s an impossible situation (as well as a vanishingly unlikely one).

Manipulative dilemmas

One of many repulsive things about thought experiments like this is that they create enmity where none truly exists. They try to force us to see born children as competing with unborn children for our mercy. It invites us to think of one or the other as less worthy, as more deserving of death. It is intrinsically manipulative and depersonalising, for both of the subjects of the story and of the person to whom the dilemma is posed.

One of many repulsive things about thought experiments like this is that they create enmity where none truly exists

Dishonest people love to set up this kind of manipulative dilemma, not only in arguments about abortion, but in all kinds of arguments that have become about so much more than the actual people involved. Dishonest people will tell you, for example, that you shouldn’t shed a tear over impoverished immigrants, because there are veterans who are homeless — as if caring for immigrants is somehow intrinsically a thumb in the eye of our veterans.

Intellectual dishonesty

They will demand to know why Narcan, used to save the lives of someone who overdosed on illegal drugs, is free, when insulin, used to save the lives of diabetics, is expensive. It pits addicts against diabetics, as if the human heart is only capable of caring for one or the other – and as if caring for one means you must despise the other.

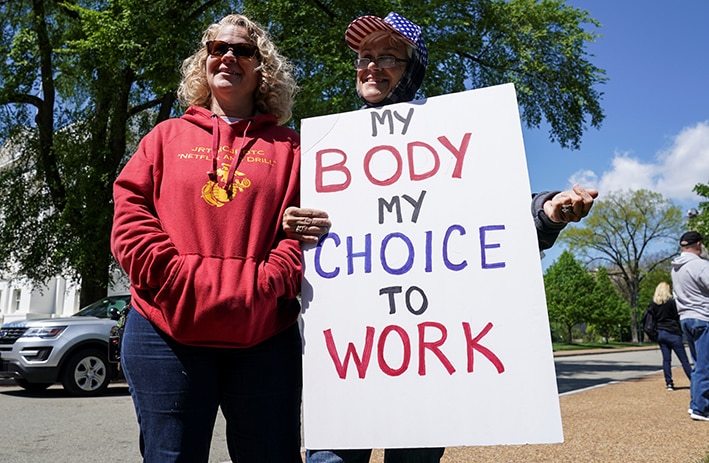

We saw this artificial enmity again, in a slightly different mode, when the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic and extended stay-at-home orders began to set in. We had to close businesses and forego gatherings and bring commerce to a crawl because, if we didn’t, thousands of people would get sick and die. But if we do close businesses and forego gatherings and bring commerce to a crawl, it will quickly bring about such economic devastation that– well, thousands of people will die.

Here is a true dilemma, not a hypothetical thought experiment. I am not sure that various governing bodies have struck the right balance between trying to protect the medically vulnerable and trying to protect the economically vulnerable.

I do know it is possible to acknowledge the horribleness of the situation, and even to make a prudent decision as best you can, knowing that someone will suffer, and still refrain from pitting one side against the other. And yet so many people have resorted to this artificial enmity between the poor and the sick.

Mocking those who disagree

Some people aren’t content with merely adhering to strict safety protocols; they must mock and deride those who are worried about keeping their families housed and fed. Some people aren’t content with making plans for keeping the economy afloat, and feel the need to sneer at people who are legitimately afraid their families will die a horrible death alone.

Why do we do this to each other? Why do we have to turn someone into the enemy? I suppose it makes it easier to work through uncertainty. It’s painful and frightening to acknowledge that some situations are just miserable. To keep us afloat in a sea of helplessness, we cling to vilification.

It is so vital to resist this urge

There is not always a good solution. Sometimes the best we can do is to acknowledge the misery of it, be as prudent as we can, and keep as much of our humanity as possible by refusing to deny the humanity of anyone involved. Just because a situation is horrible doesn’t mean we need to be horrible.

I saw the ultimate case of artificial enmity when the bishops began to rule that churches cannot hold public mass. Most of my Catholic friends were unhappy about the situation and keenly missed the sacraments, but they understood why it had to happen, and they have been trying their best to put their suffering to good use, offering it up in solidarity with Catholics who can’t receive the sacraments regularly for other reasons.

But some of them immediately set to work figuring out how they could get Mass anyway, in defiance of the bishop’s orders. Some held secret Masses in their homes, inviting friends and family; some angrily demanded that the bishop give them what they imagine they are entitled to. What struck me is how many of them said they were doing these things because of their fierce love of and loyalty to God.

Easy to attack bishops

They said that the bishops were knuckling under to civic authorities, but they only acknowledged God as their authority. They said that they cared only for spiritual good, and had no time for trivial things like the physical health of the community. They would find a way to get their sacraments because they serve God, not man.

There it is again: That false enmity. That artificial pitting of one party against the other, as if you had to choose one as worthy and despise the other as unworthy.

But in this particular set of circumstances, there was no dreadful Sophie’s choice between serving man and serving God. We serve God through serving men. “Whatever you do for the least of my brothers, you do to me.” That’s what Jesus said. Willingly foregoing the sacraments for the sake of the health of the vulnerable: This is how you serve God.

There is an irony here …

The irony is, when these great public victim vs victim debates rage, the people who argue the hardest often don’t actually have any power to act. Unless you’re a bishop or a premier or an imaginary person in the lobby of a burning IVF clinic, you’re not even in a position to make these difficult choices. The only power you have is the power to refuse to debase your heart by turning against another human being. You can opt out of that. You must.

The truth is, we always have this choice, in every awful dilemma, to serve God by serving our brother. Sometimes, what we can do for our brother is to recognise that his suffering is real. Even if we can’t do anything about it, even if we think we have to act in a way that won’t help him, we can at very least resist the urge to depersonalise him. This is how we serve our brother, and this is how we serve God. This option is always open to us. It is always, in fact, our duty.

Related

• Simcha Fisher: 15 ways to help others (and yourself) during the pandemic