18 May 2020 is the 100th anniversary of the birth of St John Paul II – an astonishing figure on the modern stage by any measure. Fr Max Polak reflects on the times and the significance to the Church and the world of this beloved pontiff and saint.

Do you believe in divine providence? If not, it is probably because you expect God to act in simplistic ways, and He does not. For one thing, He respects human freedom, and so his way of being present to events – either personal or of a worldwide scope – easily escapes our perception. What we generally see so easily is the messy result of human choices. But there is something deep down there that is the mighty, masterful “hand of God.”

A providential election

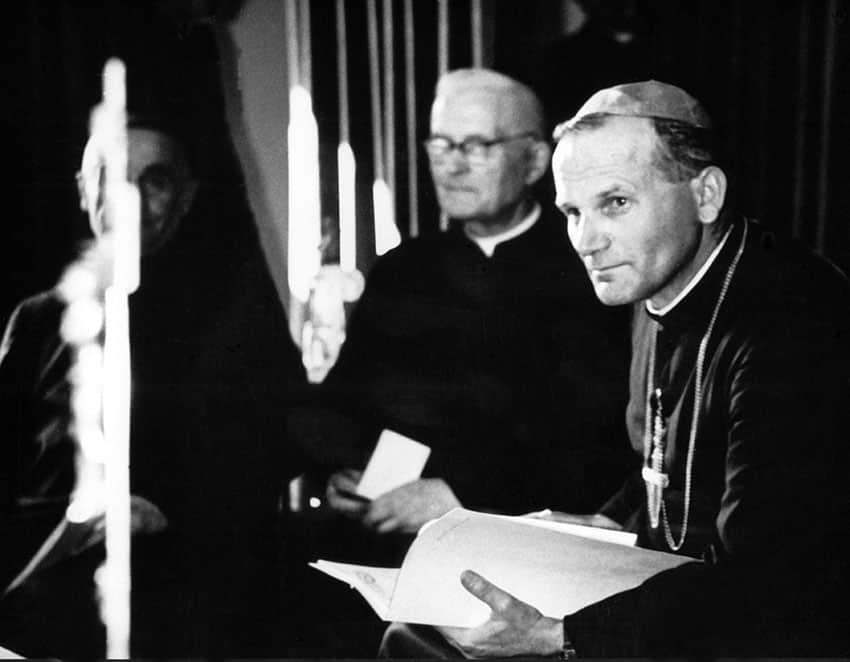

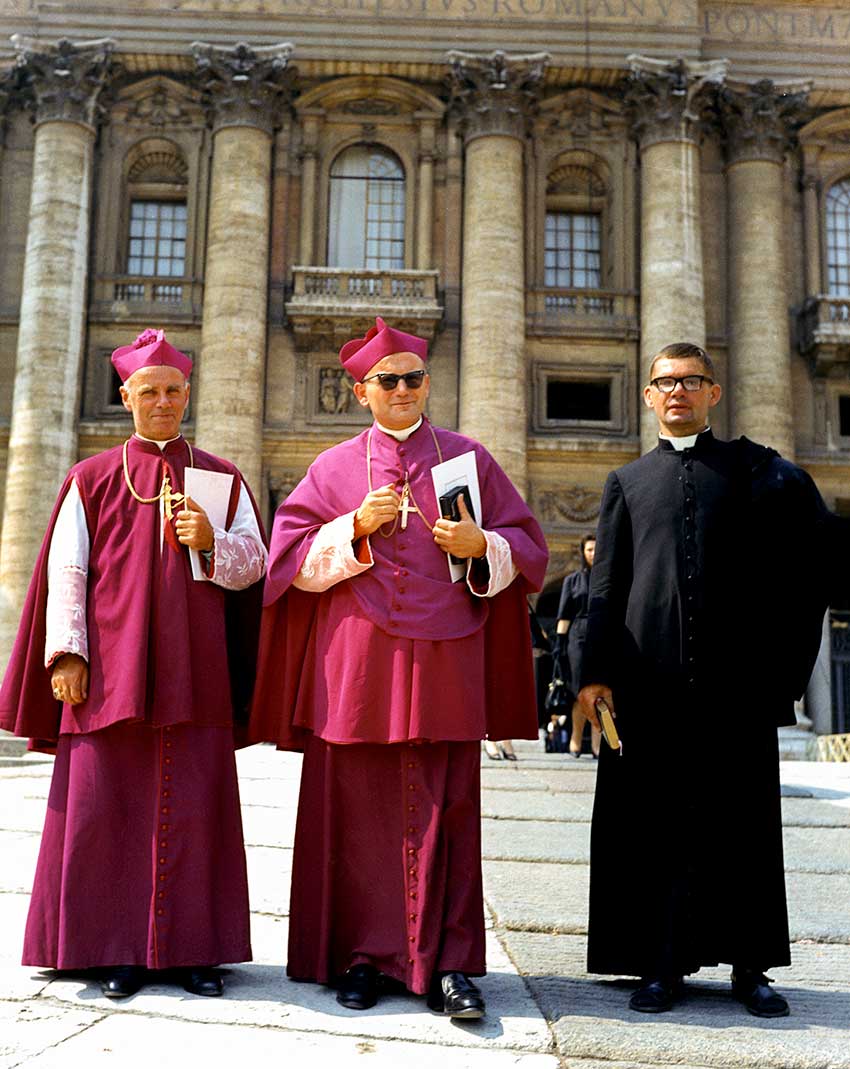

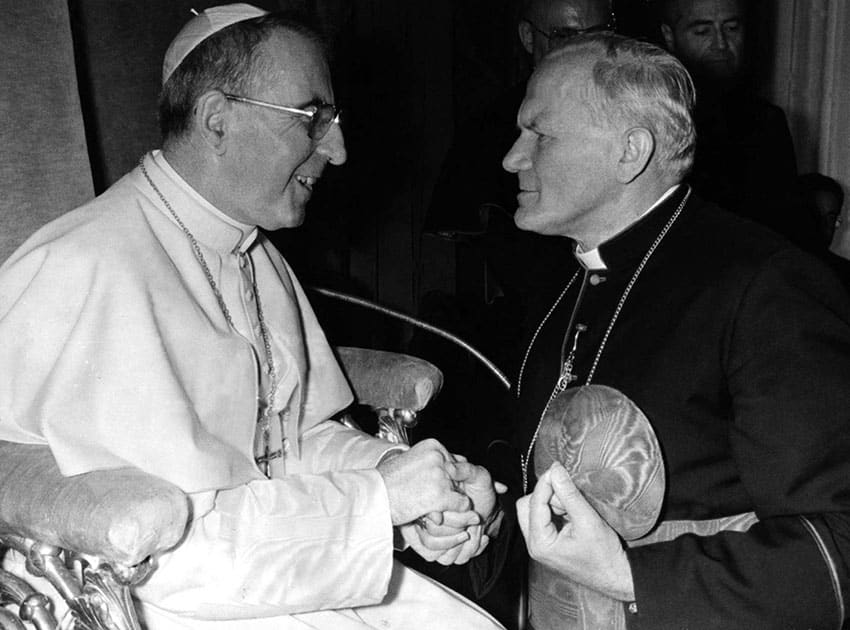

Just the same, there are times in history when God, tired no doubt of just how messy things are getting, decides to show his hand. Even then, the sceptics may not notice. They may be too self-absorbed or too opinionated. An example of this is the failure of many, even in the Catholic Church, to capture the providential significance of the election, on 16 October 1978, of Karol Wojtyla, the Cardinal Archbishop of Krakow, Poland.

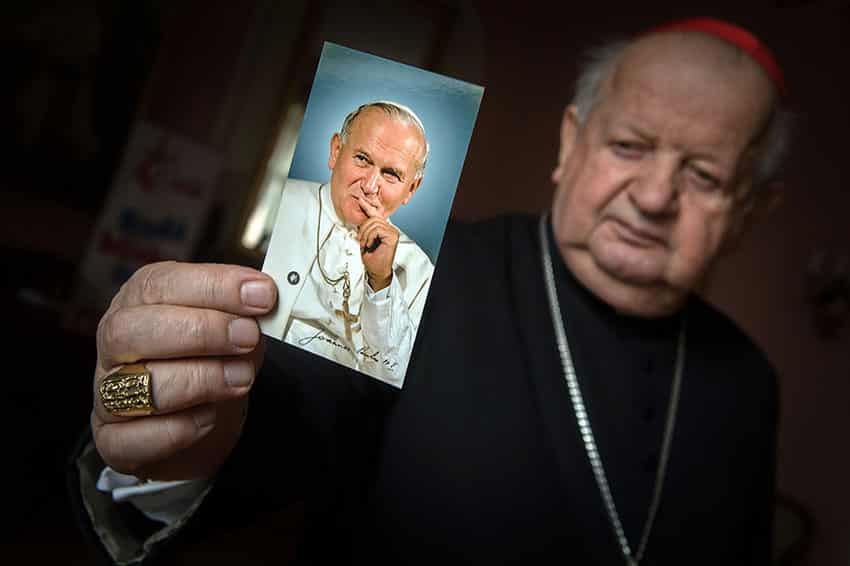

Wyszynski guessed

Like many still alive today, I distinctly remember that day. I found myself in a rather isolated place and so I heard the news only late in the day. My feeling of surprise and excitement was huge. Certainly, very few people, least of all the all-pervasive media, expected that this rather obscure prelate – obscure outside of Poland that is – would be the cardinals’ choice.

Yet, evidently, there was one person who, years before, had predicted it – the soon to be beatified Cardinal Primate of Poland, Stefan Wyszynski.

A bittersweet election

The appearance of Karol Wojtyla on the world scene, taking the name John Paul II, was a masterful play of God’s providence. It was beautifully orchestrated. He was elected on the feast of St Hedwig of Silesia, a duchess saint important in Polish history, having been born on the 18th May, 1920, currently the feast of Pope John I. The bittersweet aspect to his election was that it followed the premature death of another Pope, who had already won the hearts of many in his brief, 33 day-pontificate – Albino Luciani, known as Pope John Paul I.

A philosopher and an artist at heart

The election of a bishop from behind the iron curtain, the first non-Italian in centuries to occupy the papacy, was an outcome that sent shock waves through the Soviet hierarchy. It would soon prove to be the beginning of the end for a monolithic empire. Here was a man tempered like steel by suffering, an immediate witness to the cruelty and injustice of two successive, atheistic and amoral regimes. Here was a relatively young, energetic and attractive personality. Here was a philosopher who had carefully analysed much of the philosophical thought of the twentieth century. Here was a man familiar with the world of culture, of the art of theatre, and of the spoken word.

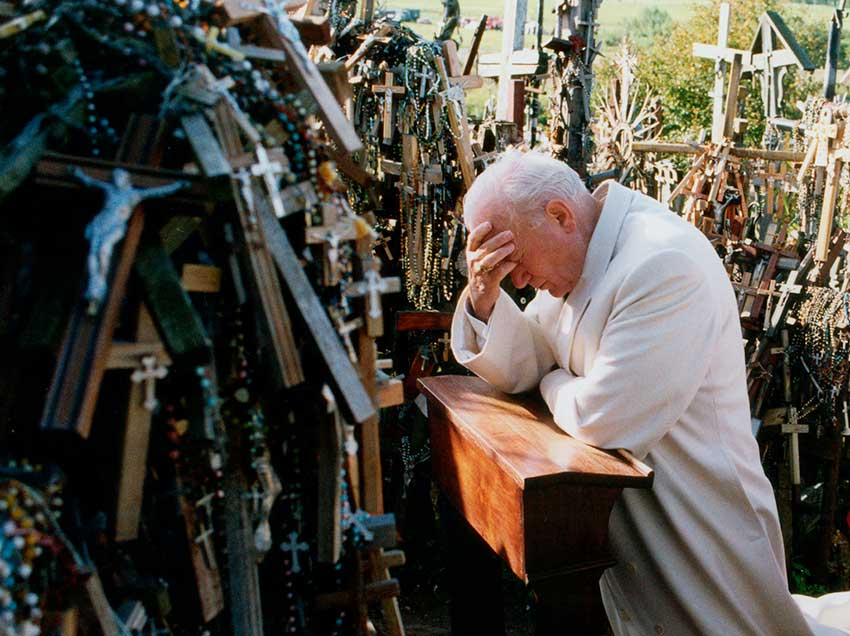

A certainty need by the time

Nevertheless, the most important thing about John Paul II was his unshakeable Christian faith, his love of Jesus Christ and of his blessed Mother Mary. These would constitute the power of his papacy, which was both strong and gentle, firm and merciful.

In fact, some 11 years after his election, what seemed impossible came to pass. The forbidding edifice of the Soviet Union unravelled, with barely a shot fired. It was the follow-on of the momentum created by his first historic visit to Poland in which he spoke convincingly of genuine freedom, the Catholic faith that underpinned much of the nation’s history and culture, and the hope of a better future.

One man and a revolution

In an interview late last year, Janusz Kotanski, Polish Ambassador to the Vatican, reflected: “The Communist party was always saying: ‘Yes, we are here for you! We are for the workers! For the poor people! However, these people were now saying, no. It was a kind of revolution that was absolutely peaceful. The people were praying their rosaries and on the gate of the Gdansk shipyard, there was a portrait of John Paul II… I know it was also, of course, the weakness of the Soviet Union’s economy, Ronald Reagan’s very good and strong policies. However, who started it? Who did it? St John Paul II, Karol Wojtyla and the millions of Poles who were not afraid.”

A church in relative disarray

World-changing as was the Pope’s influence on Eastern Europe, it would be wrong to assess the papacy of John Paul II primarily in political terms. He was a man of the Church, and the Church would be his greatest concern for the length of his 27 year pontificate. The aftermath of the Second Vatican Council, which in itself was a colossal achievement for the Catholic Church, was hardly blissful. The Council produced teachings both rich and promising of genuine renewal. However, the diverse agendas of a number of influential theologians and many clergy meant that an atmosphere of uncertainty and even confusion dominated.

Priesthood and religious life waver

Numerous priests and religious abandoned their commitments. Liturgical experiments abounded, at times projecting a superficial interpretation of the sacraments. Seminaries stumbled over what sort of formation was called for. It was not uncommon, as Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI pointed out early last year, for a highly deficient kind of moral theology to be taught to young seminarians and, of course, more widely as well.

Initiative in a crisis

John Paul II found the situation of the Church in western countries to be in a state of crisis. Along with genuine rejuvenation, there was division, dissent, laxity, and subsequently, as we know all too well, scandal. The heroism of this Pope was to put his all into a vigorous catechesis, and a call to order. Not everything was negotiable. There is dogma and there are objective moral norms. From his pen or under his auspices there emerged a series of remedial documents, some of which are to be regarded as landmark teachings.

Veritatis Splendor and courage

In the camp of moral theology, one ought to mention the encyclical Veritatis Splendor. Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI considers this one of his most important contributions to Church doctrine. In a 2014 interview, Benedict reflected that the Polish pontiff “did not ask for applause and never looked troubled when he was making difficult decisions … He acted in accord with his faith and beliefs, and he was willing to endure blows against him. I could and should not imitate him, but I did try to continue his legacy and his mission the best way I could.”

There is barely any aspect of doctrine that John Paul II failed to revisit, not only to confirm the faith of Catholic Christians but to deepen their understanding and appreciation for what is referred to as “the deposit of the faith.” Longevity, against the odds posited by the near fatal assassination attempt, in 1981, enabled him to do this.

New vistas – theology of the body, social teaching

Yet he also opened new horizons. A well known example are his teachings on marriage and human sexuality, often referred to as theology of the body. He promoted the goal of a civilisation of love, insisting that the fundamental vocation of the human person is the vocation to love – sacrificial love, that is, be it in the self-giving form of marriage or that of celibacy. His reflections on the Holy Trinity represent a fresh revisiting of what is the central article of the Church’s faith. He accomplished this in the form of numerous addresses in the lead up to the new Millennium. Under the leadership of this far-sighted and charismatic successor of Peter, the Church would receive nothing less than its first universal catechism in over 400 years. He also commissioned the first ever compendium of the social doctrine of the Catholic Church.

Holding strong amid anarchic currents

During his watch, the massive revamping of the canon law of the Church, initiated by St Paul VI, would reach its successful conclusion. Liturgical abuses were already being responded to at the time of the Polish Pope’s election, but his teaching and example greatly helped to ensure the preservation of dignity and reverence, especially for the Eucharistic Sacrifice and Presence.

Ecumenism

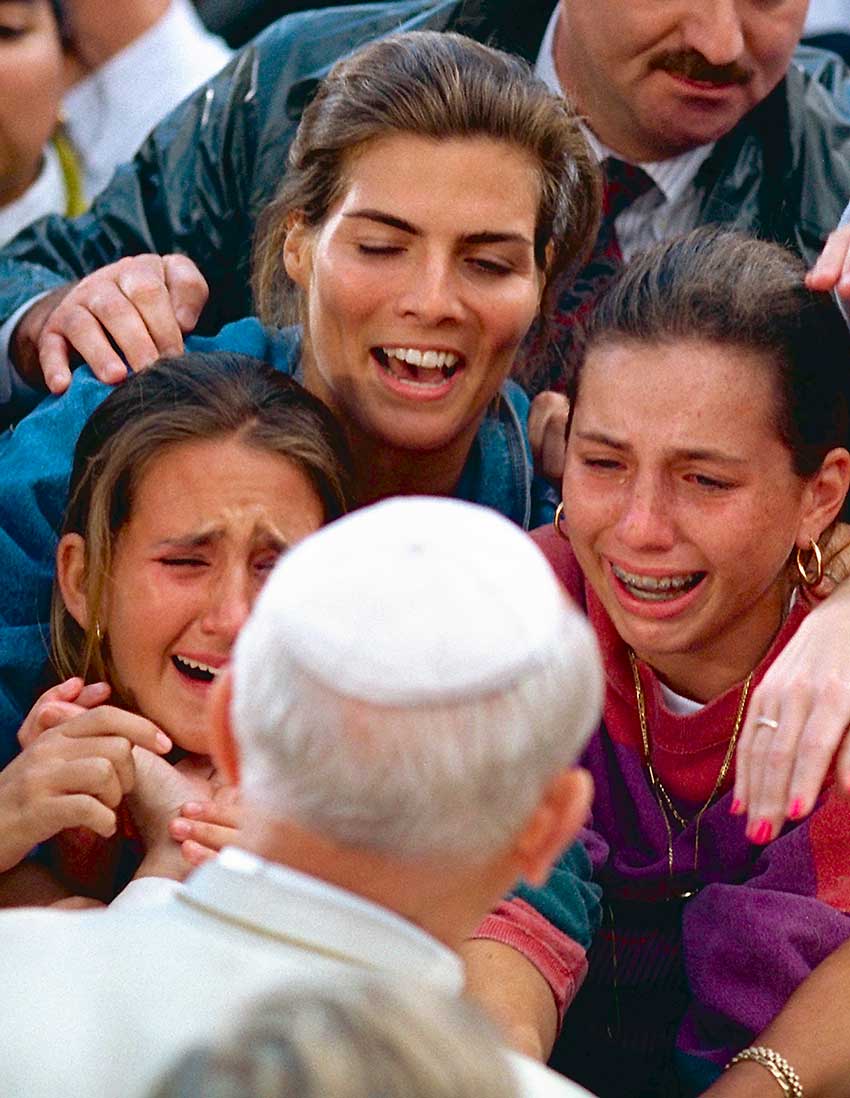

It would be unfair to describe John Paul II’s pontificate as principally reformist. His vision led to an incredibly extensive outreach to the world. Of the 195 nations currently existing, the Pope visited 127. His reception was almost without exception warm, or outstanding, and at times tumultuously joyful, engaging even those not of the Catholic persuasion. He moved ecumenism and inter-religious dialogue onto a new scale.

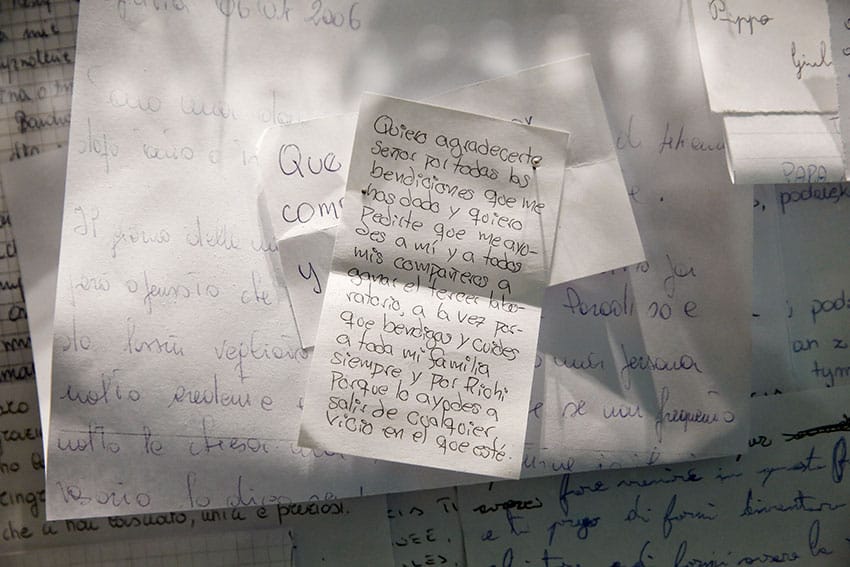

A faith that made others question their lives

St John Paul II’s faith was a lived and tested faith that moved people to reassess their own relationship with God. Numerous have been the conversions to Christianity, and to the Catholic Church that he was instrumental to. So also did he attract many young people – especially through the World Youth Days – to commit to a more genuine practice of Catholic Christianity, even sparking a revival of vocations to the priesthood and religious life.

A prolific papacy

In a short reflection of this kind, important things get left out, and so it will be subject to any number of criticisms. Why not mention his promotion of the Divine Mercy devotion? (I just did!) Why not his pro-life manifesto Evangelium Vitae? Why not his extraordinary attachment to the Virgin Mary? Yes, why not. There are so many great books to read, and there will be more to come.

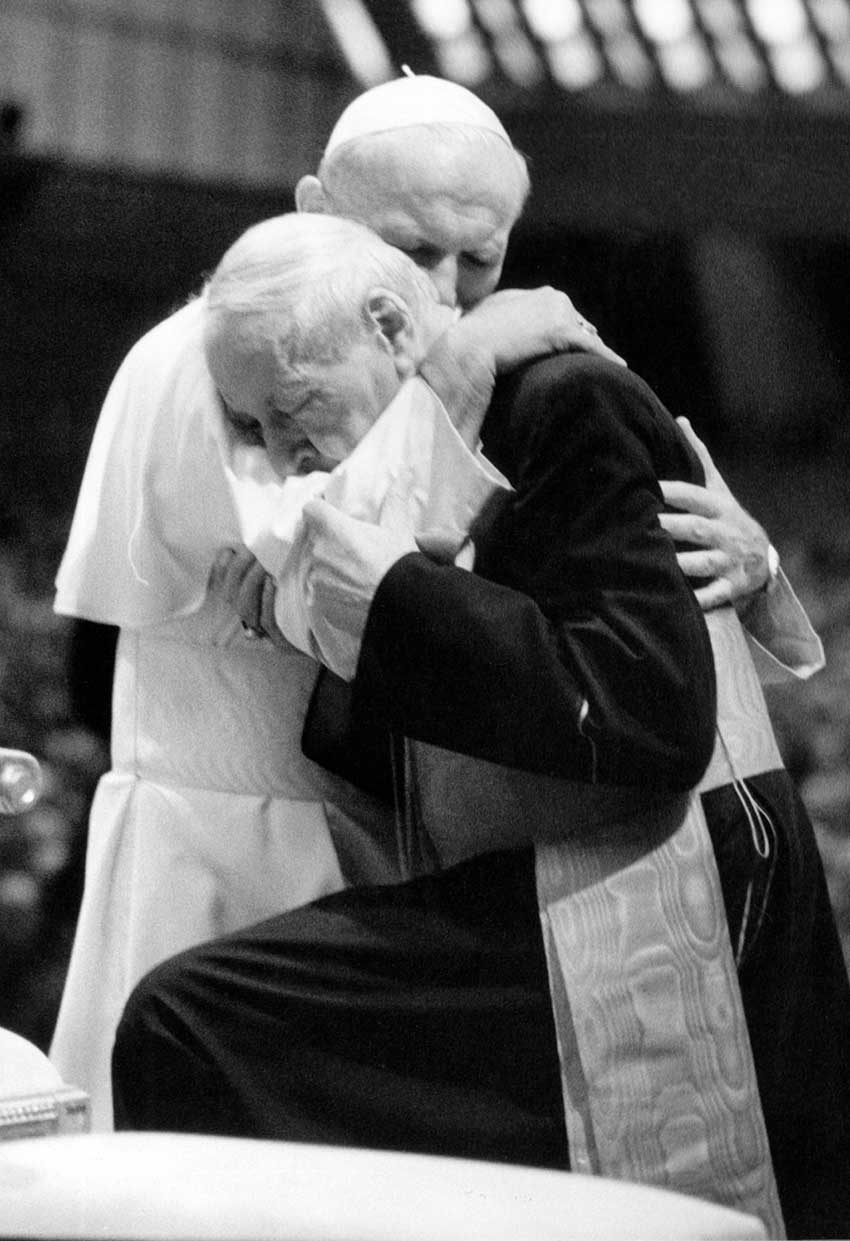

When Pope Benedict XVI was asked whether he always regarded John Paul II as a saint, he replied: “The reality that John Paul II was a saint became increasingly apparent to me in the years I worked together with him.” Though he would beatify Karol Wojtyla in one of the quickest such acts in history, it would be Pope Francis who would declare him St John Paul II. Some would like to excessively contrast the present Holy Father with his predecessor. They are certainly different, but not in their catholicity, and both pontiffs will be known for their emphasis on compassion and their apostolic fervour.

An extraordinary role – but an ordinary man

In looking upon John Paul II as a kind of hero, and acknowledging his personal holiness, we must not lose sight of his humanity, his struggles, his suffering, and even how, in spite of his prudence and wisdom, there were those who managed to deceive him and others who undermined him. Every Pope, and even the saints, must admit to failings of one kind or another. This is the human lot. Yet the providence of God was showing itself in full colour in so much of what this humble and persevering man was able to accomplish in 27 years at the helm of Peter’s boat.

Fr Max Polak is currently based in Brisbane. He has written extensively on St John Paul II.