Living life and faith online is a double-edged sword

“It’s not real life; it’s just online.”

This is something I’ve heard a lot over the last few years. People have said it derisively, claiming that online friends aren’t real friends, and online relationships aren’t real relationship; and they’ve said it soothingly, so alarmists like me would stop overreacting about the threat from silly, lame online gamers who chatted incessantly about revolution but never actually made it out of their mum’s basement.

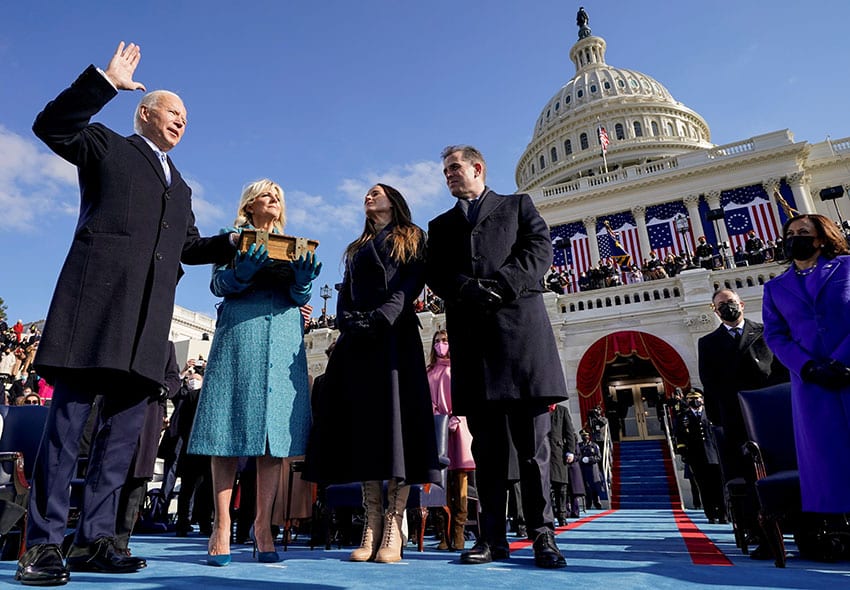

Then came the assault on the capitol building, and I do believe that’s the last time I heard anyone say “it’s not real life; it’s just online”. Some of the people who made it into the building were truly silly, albeit also dangerous; but many had been grimly, purposefully planning an organised revolution, complete with public executions.

It was real as could be, and it could not have happened without first starting online — with far-flung people meeting each other online, normalising, amplifying, and escalating each other’s worst and craziest ideas, and then working together to put it into action in real life.

“Things that start online can become very real, and we don’t have the luxury of assuming that threats will stay in the realm of the potential.”

It started out virtual, but five real people are dead in real life, and dozens, maybe hundreds, are going to jail. Things that start online can become very real, and we don’t have the luxury of assuming that threats will stay in the realm of the potential.

I’d like to shift gears now and talk about another kind of threat, and another kind of potential revolution.

It would be hard to understate how much Americans cherish freedom of speech. It’s perhaps especially hard to see it right now, when there is so much disingenuousness and so much confusion about the limits of that freedom.

In the final days of the Trump presidency, Twitter and Facebook suspended the president’s accounts, because he was disseminating dangerous lies, and the courts have ruled that Apple has the legal right to refuse to host Parler, the social media platform that refused to regulate dangerous speech on its site.

As often happens in a crisis, there was lots of confusion about who actually has what rights. When platforms moved to cut off people fomenting violent dissent, a certain number of innocent people got caught up in the broad net — myself included. My best guess is that a bot misread some combination of words as incendiary. At the same time, lots more people claimed to be innocent and unjustly persecuted, when in truth they were simply facing the overdue consequences of their misuse of free speech.

It’s fair to say that there was a purge of conservative voices on social media, but this happened not because conservatism itself is suffering persecution, but because so many conservatives have become cozy with people whose words and ideas are dangerous and violent, and whose online life very demonstrably spills out into real life.

So that’s a real thing. Far right domestic terrorists are by far the most pressing violent threat to the nation, and for the last four years, our president has been their friend. Now we have a new, more liberal administration now; and while our new president is himself fairly moderate, much of his administration is more progressive, perhaps even radical.

So even though the explosive threat from the far right is far from diffused, and even though I applaud ongoing efforts to clamp down on platforms that help that threat emerge from online into real life, I am well aware that this is not the only danger we face. Sometimes, under the guise of saving the nation from exploding, we instead run the risk of imploding.

“Never let a good crisis go to waste” is a real thing, too. There have always been Americans who adore the idea of quashing free speech, and who will use the current crisis to prolong the clamp-down on speech, and make it permanent, and expand it. Do not think that Trump and Qanon are the only ones who drum up fear and paranoia to exploit the masses.

“There is a clear and present threat from the far right, but that doesn’t mean there’s no threat from the far left.”

There is a clear and present threat from the far right, but that doesn’t mean there’s no threat from the far left. And here is where Catholics in other countries may be more familiar with the threat I see in the far distance.

There really are people who wish they could make it illegal or impossible to teach the things the Church teaches. I think it’s inevitable that, even as heterodox Catholics like our new president take their place on the public stage, orthodox Catholic thought — especially as regards sexuality, marriage, euthanasia, and education — will be less and less welcome.

Because we haven’t been careful enough to make a clear line between faith and politics, a lot of purely religious freedom of expression will get crushed along with dangerous political thinking. I think it’s possible, even likely, that orthodox Catholics — not super trads, but just normal, reasonable people who do their best to assent to the basic teachings of the Faith — will be chased offline in the name of safety.

I know that sounds crazy. I’m okay with sounding crazy. Frankly, I’m not convinced that, if this suppression happened, it would be a completely bad thing. Let’s imagine for a moment that the political winds shift very drastically, and Catholics are someday forced to retreat offline. Will it be good or bad for our faith?

Let’s look back over the last decade. Has social media been good for the Church? Yes: It’s allowed us to stream Mass online when we can’t physically be there. It’s allowed someone in pain or distress to ask for prayer, and to instantly have thousands of strangers praying for them.

It’s allowed isolated Catholics to find far-flung friends who understand, support, encourage, and teach them, when no one who’s physically close to them will. It’s given us instant access to the liturgy of the hours and the Bible and endless choices of litanies and prayers online. There are a thousand ways the internet has allowed Catholic thought to flourish and to reach people who never would have been reached before.

It’s also been horrible for the faith. Far left and far right Catholics have huge followings on social media, and giving them a platform for insane, pernicious lies that great heretics of the past could only dream of. It’s allowed for the scandal of Catholics, including priests, to be outrageously vicious to each other in the name of Christ. It’s allowed all manner of insanity to be normalised, amplified, and escalated, and labelled ‘Catholicism’.

And there’s something I’ve seen over and over again: When Catholics are extremely present online, even when there’s nothing wrong with they way they express their faith online, online is all there is.

“it’s just too easy to fall into thinking that our online life IS our faith”

So let’s think about what would happen if all those Catholic voices, good and bad, were silenced online. Let’s think about how much of our faith is online, and what that means.

There is always the danger that things that are just online will bust through into the physical world, with horrendous consequences. People act on things they shouldn’t even be talking or thinking about. But for most people, the bigger danger is the opposite: That the online world never leads them to act in real life, even when they should.

The things they should be living get trapped in an endless bubble of talk (and video, and podcast, and discussion threads), and it’s just too easy to fall into thinking that our online life IS our faith. This is a danger that even orthodox, sensible, non-loony Catholics are prone to. It’s all in the ether, but it feels so real, so busy, so active, so intense.

This is the thing I struggle with. I will gab about artwork depicting the corporal works of mercy and never get around to checking in on the old lady who lives next door. I will argue for 40 minutes about the true meaning of charity and get so frustrated I call someone a turd. I fulminate on canon law but do as I please. I will write about Jesus all day long and never think to talk to him. I disseminate prayers but never pray. These are all the fruits of having a very online faith. Hell is paved with the skulls of online Catholics.

So whether or not my dark musings about the future of Catholicism in America ever come true, we might ask ourselves: What would actually happen if we did lose our online presence? The Church itself would survive, for sure; but what would happen to our own personal faith if it all had to go offline? What would happen to our faith if we had to live it exclusively in real life? What would change, for better or for worse? What changes would we have to make?

And once we think about that, we could ask ourselves what changes can we make right now? Because no matter what happens to the internet, night cometh, when no man can log on. For each of us, there will come a day when we lose connectivity with every other human being, and we will stand alone, face to face with the Lord. What’s your offline plan?

Related: