Children’s confessions deserve just as much respect

Recently, I’ve come across several instances of people taking the seal of confession lightly. Not priests, thank God (although I have heard priests disclosing things that skirted too close to the line), but laymen — specifically, laymen talking about their children’s confessions.

(Before I go any further, here is my vital reminder: If you do encounter a priest who has broken the seal of confession, or if you find evidence that this has happened, SAY SOMETHING. Tell his bishop, and demand a response. This is a big stinking deal and you should make sure it gets addressed. A priest who breaks the seal of confession needs to be stopped ASAP.)

“If they see you treating children’s confessions as ‘confession lite’, then that is how they will approach it themselves”

Carelessness around children’s confessions represents two failures: A failure to take confession seriously enough, and a failure to take children’s spiritual lives seriously enough. Both can be disastrous; or, at very least, they can erode our understanding of what sacraments are for, and therefore erode our faith.

Here is a refresher. The seal of confession means a priest can never tell anyone, for any reason, what he heard in the course of a confession. He also cannot act on what he has learned in the confessional. He cannot even talk about what he heard in confession to the person who confessed it. A penitent cannot “waive the seal of confession” and give permission to a priest to discuss what was confessed. If the penitent wishes to discuss what he confessed, he must say it all over again outside of the confessional.

A seal is a seal, and cannot be unsealed. What a penitent says does not leave the confessional in any way, by any means. If a priest does betray the penitent in this way, he incurs latae sententiae excommunication. This punishment has also been imposed on priests who violate the seal even indirectly by sharing information that makes it possible for people to connect a sinner with something revealed in confession. A priest cannot even acknowledge that a person has confessed to him.

The absolute secrecy of the seal

Here’s something many Catholics don’t know: The seal of confession also binds to secrecy anyone who hears what a penitent says in confession. So if you’re an interpreter, or a worried parent, or a stranger who was standing too close, or if the penitent was too loud, and somehow you heard what someone said in confession, you cannot ever tell anyone what you heard, for any reason. You are bound by that seal, just as much as the priest is. This is for the spiritual good of the entire Church.

Fr Sam Sawyer explains it this way:

“[T]he seal of confession is not a contract between the priest and the penitent. The person who confesses has the right to privacy, but that’s only the beginning of what the seal protects. The Church wants to maintain the absolute freedom of anyone, under any circumstances, to seek God’s mercy without fear. If the seal of the confessional can be broken, for any reason, then that potentially becomes an obstacle to someone seeking to confess.”

The priests I admire most generally keep an even wider perimeter around the seal than is strictly mandated, because they take it so seriously, and because they understand how disastrous it would be for us all if the seal were made vulnerable. And here is where I see people muddying the waters, doing and saying things that may or may not technically violate the seal of confession, but which reveal a careless disregard for its seriousness:

Joking about meeting someone in the confession line;

Taking pictures of kids going into the confessional or coming out, or even occasionally of kids actually confessing;

Talking about how cute it is that your child confessed such-and-such (and maybe you know about it because the child told you, or because you found a crumpled piece of paper with a list of sins).

I also heard a story of a priest coming out of the confessional after absolving a group of newbies and saying, “Who are the parents of this child?” The parents nervously identified themselves, fearful that something had gone wrong; but the priest just wanted to compliment them on how well the kid knew his act of contrition.

These are all things that don’t violate the seal of confession. But they are too close for comfort, and they can damage the holy fear we should cultivate around the seal.

The spiritual lives of children should be taken seriously

And this brings me to my second point. There is also something like holy fear we should feel when we’re dealing with the spiritual lives of children in general. It’s easy to become cavalier about it, because kids are so noisy and ridiculous and smelly and cute and funny and weird and, well, childish. When we are responsible for wiping their butts and feeding their bellies and drying their tears and sometimes physically moving them to where they need to be, it’s easy to fall into thinking of them as objects or possessions or lesser beings, as somewhat less deserving of human dignity than adults.

Some of this is unavoidable. It’s hard to treat someone with dignity when he’s taking his pants off and running through the produce section of the supermarket. But there is a kind of dignity that is appropriate even to children, and this is something that comes up often, and urgently, when we’re caring for their spiritual development.

So let me say it plainly: A child in confession is just as entitled to absolute privacy and respect as a penitent of any other age. If you wouldn’t tease or harass an adult about being in confession, do not do it to a child. If you wouldn’t treat an adult’s confessed sins as a joke or as a public spectacle, even affectionately, then do not do it with a child.

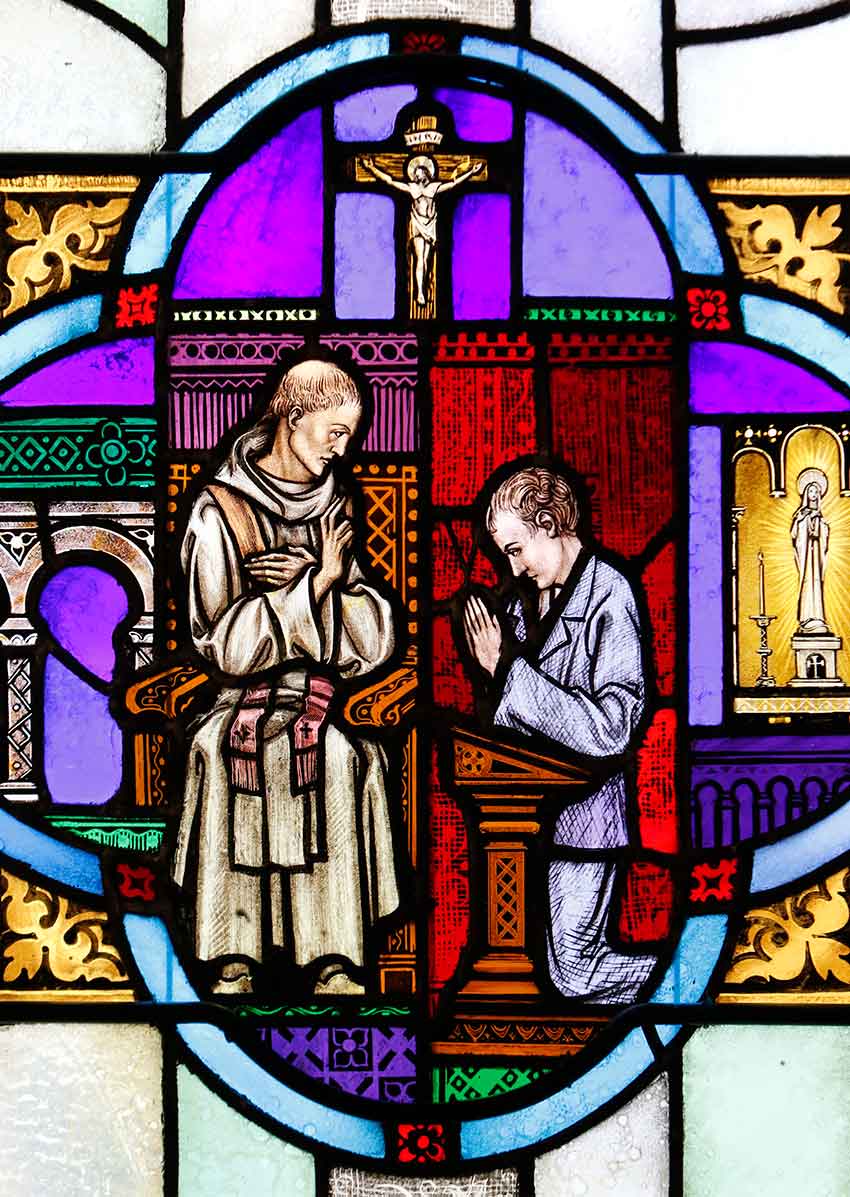

Jesus meets a child in confession just as surely as he meets an adult. It is a sacred moment, and should be treated as such, with dignity and respect.

Children deserve this respect for their confessions by virtue of their humanity; and they also learn from the way adults behave. If they see you treating children’s confessions as “confession lite,” then that is how they will approach it themselves — and perhaps when they grow older, they’ll decide it’s something to leave behind with other childish things they’ve outgrown.

You can joke about confession in general. It’s kind of funny. You can be lighthearted about it, and treat it like a normal human thing to do, which it is. But you should not treat an individual child’s confession as something foolish or public; and you should not, by your words or actions, imply that it’s somehow a watered down version of the real thing.

It is a real thing, and so we should make a wide, careful, respectful perimeter around it. This is for the sake of the individual child, and also for the sake of everyone who witnesses the way the Church understands the sacrament. Either it’s real or it isn’t; and if it’s not real sometimes, then the hell with it.

Related articles: