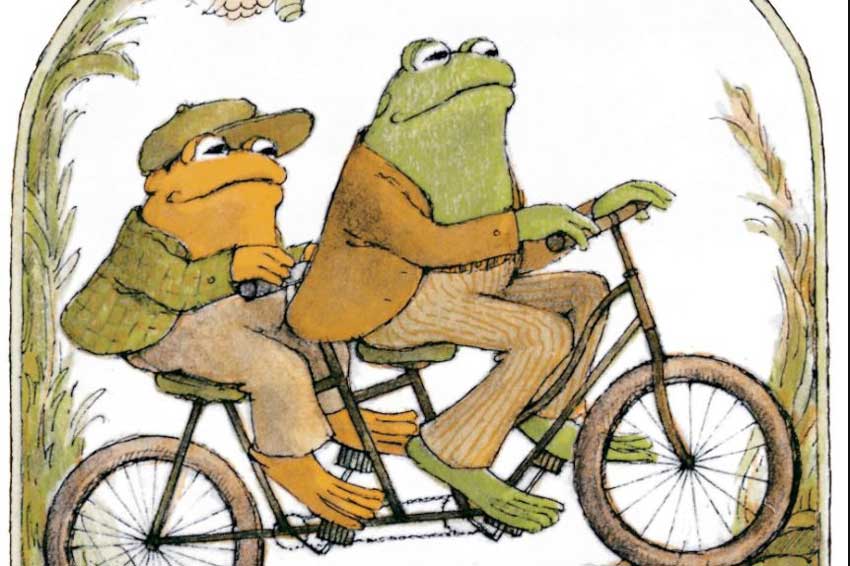

In the story ‘Alone’ from the beloved children’s book Days with Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel, Toad goes to visit his friend Frog, only to discover a note on his door saying that Frog wants to be alone.

Toad, as is his wont, immediately falls into a panic, assuming Frog no longer cares about him. He puts together an elaborate lunch and hitches a ride on a turtle’s back, launching himself out across the water toward the island where Frog is, intending to win his affection back. As he comes in earshot of the island, he shouts,

“Frog! I am sorry for the dumb things I do. I am sorry for all the silly things I say. Please be my friend again!” Then he slips and falls, sploosh, into the water.

Every time I read this story, I laugh, because Toad’s words are so familiar. They are, in effect, an act of contrition, and I am Toad.

We are all Toad. What we may not all realise, though, is that an act of contrition can be expressed in many different words, including something like what Toad shrieks out in his misery. Many of us were made to memorise a particular prayer when we were growing up (or when we joined the Church), but we don’t have to say that specific prayer.

When the Rite of Penance describes a sacramental confession, it says, “The priest … asks the penitent to express his sorrow, which the penitent may do in these or similar words . . .” and it suggests 10 possible prayers, and leaves room for anything that expresses contrition.

Many people in my generation can rattle off something like this one:

O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended You, and I detest all my sins, because I dread the loss of heaven and the pains of hell [or: because of thy just punishments]; but, most of all, because they offend You, my God, Who is all good and deserving of all my love. I firmly resolve, with the help of Your grace, to confess my sins, to do penance, to avoid all occasions of sin, and to amend my life.

or this shorter one:

Oh my Jesus I’m heartily sorry for having offended thee, who are infinitely good, and I firmly resolve, with the help of the grace, never to offend thee again.

About 93 per cent of Catholic children hear “hardly” instead of “heartily.” A few enterprising children thread this needle by saying, “I am hardly sorry for having been a friend of thee.” And that works. It’s the sincerity that matters, not the getting it perfectly right.

“[T]he Act of Contrition is not primarily a magical formula rattled off thoughtlessly to guarantee instant forgiveness. Rather, it expresses in words a deeply personal act that engages a person’s affections and will.”

So it’s less important to have something memorised, and more important to think deeply about what we intend. A good act of contrition should include an expression of sorrow, a renunciation of sin, and a resolution to change; and there are many different ways you can say it.

Here’s a rather passionate one, from Evangelii Gaudium:

“Lord, I have let myself be deceived; in a thousand ways I have shunned your love, yet here I am once more, to renew my covenant with you. I need you. Save me once again, Lord, take me once more into your redeeming embrace.”

and one that brings to memory our place as part of a larger community of the Church Militant:

“Lord Jesus, you opened the eyes of the blind, healed the sick, forgave the sinful woman, and after Peter’s denial, confirmed him in your love. Hear my prayer, forgive me of my sins, and renew your love in my heart. Help me to live in perfect unity with my fellow Christians, so that I may proclaim your saving power to all the world.”

Here’s one that’s rapidly becoming my favorite, because the brevity of it is a good reminder that it’s not about me, it’s about Him:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the Living God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Another popular option: Your own house blend. You start off saying one, and then it morphs into another, and you finish up with the last part of a third. And Many Catholics don’t have anything memorised, so they just read off whatever’s tacked up on the wall of the confessional (assuming they’re lucky enough to be in a parish that accommodating!).

But if you don’t have anything memorised and there’s no cheat sheet on the wall, you can tell the priest they aren’t sure what to say next. The occasional difficult priest might possibly respond with irritation or impatience (and if that’s happened to you, I’m sorry, and I’m angry on your behalf); but it seems to be more common these days that priests are simply glad you’re there, and will be glad to help you, and will probably even admire the courage it takes to show up when you’re so nervous and uncertain.

As it says in the Catechism, “The confessor is not the master of God’s forgiveness, but its servant. The minister of this sacrament should unite himself to the intention and charity of Christ.” (1466)

I remember hearing of a priest who was called to attend the death of a wicked old sailor who’d spent his life in debauchery, drinking, gambling, stealing, and carousing with women. The priest knew this wasn’t a thoroughly catechised man, and so simply asked him, “Are you sorry for all the wrong things you’ve done?”

The dying man considered for a moment, and even as he lay expiring, he was overwhelmed with happy memories of all the pleasures he enjoyed. He truthfully answered, “Father, I have to admit, I had such a good time that I’m not really sorry”.

Realising he only had a few breaths left in him, the priest said in desperation, “Well, do you WISH you were sorry?”

“Yes!” the man answered. And so the priest absolved him. Extremely imperfect contrition for the win.

I don’t know if this really happened, but what the story conveys is true: We really only have to make the smallest movement toward regret, and the Lord leaps into the breech and does the rest.

It has never been about our efforts, and it certainly has never been about getting the formula just right — saying the correct incantation to conjure up forgiveness. It’s about sincerity — or, in the case of the dying sailor, even a desire for sincerity.

And what about poor Toad? After his contrite cri de coeur, he falls off the turtle’s back and falls into the lake. And Frog is at his side in no time. He pulls Toad out of the water, and they retrieve what’s left of the desperately-made picnic lunch with which Toad put together hoping to win back Frog’s friendship.

And it turns out Frog didn’t really want to be away from Toad. He wasn’t miserable or angry, as Toad feared. In fact, he was thinking of Toad all along. Frog says:

“I am happy. I am very happy. This morning when I woke up I felt good because the sun was shining. I felt good because I was a frog. And I felt good because I have you as a friend. I wanted to be alone. I wanted to think about how fine everything is.”

The he tells Toad that now he will be happy *not* to be alone, and they eat their waterlogged lunch together.

Frog is not precisely a Christ figure; let’s not get carried away. But there is something wonderfully familiar in the way he so readily welcomes the ridiculous Toad onto his little island and accepts his well-meant gift, even if it is only soggy sandwiches and an empty pitcher.

There was never any loss of love, only a lack of faith.

Frog did want to be alone for a while, but the plan all along was for them to come together again.

Lord Jesus, Son of the Living God, please be my friend again. Amen.

Related article:

Simcha Fisher: How I’m teaching about confession with the Sheep Game