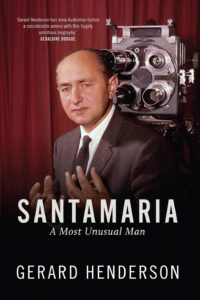

The centenary of the birth of Bartholomew Augustine Santamaria – 14 August, 2015, – has been commemorated with the publication of a biography by Gerard Henderson, executive director of the Sydney Institute.

The centenary of the birth of Bartholomew Augustine Santamaria – 14 August, 2015, – has been commemorated with the publication of a biography by Gerard Henderson, executive director of the Sydney Institute.

While studying at Melbourne University in the mid-1960s the author first met Bartholomew Santamaria (or Bob or BA Santamaria as he was more commonly known).

He subsequently worked for Santamaria in a range of roles including as a part-time researcher in 1970-1 and as a journalist for News Weekly, a periodical established by Santamaria.

He also worked on a doctoral thesis in the 1970s focusing on the political and social activities of the Catholic Church in the mid-20th century, which was subsequently published as Mr Santamaria and the Bishops.

For the biography he has comprehensively researched the life of Santamaria over many years including interviewing many of his critics and supporters. This extensive research and reflection has resulted in an authoritative biography of one of the most significant political and religious figures in Australia in the 20th century.

The book begins with the death of Santamaria on 25 February, 1998, at the Caritas Christi Hospice in Melbourne.

The principal celebrant at his funeral at St Patrick’s Cathedral was the then Archbishop George Pell and was attended by some 2500 mourners including an extensive range of community leaders including the then Prime Minister John Howard, Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett, Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer, federal Treasurer Peter Costello, Tony Abbott, Barry Jones and Lachlan Murdoch.

The media reporting of his death was so extensive that for the week commencing 23 February, 1998, he topped the list of the most mentioned people in the press ahead of Kofi Annan, John Howard and Bill Clinton. As Henderson notes, this was a ‘remarkable achievement for an Australian who died at the age of 82, who never held an elected or public office, who never lived outside Melbourne and who was invariably identified by reference to his Catholic faith’.

The remainder of the book focuses on providing the reader with an understanding of the life and works of Santamaria that helps explain the extraordinary community response to his death.

Key formative experiences from Santamaria’s early life are described in detail including the inspiring example of his Italian migrant parents, his early education by the Christian Brothers and his academic success as an Arts/Law student at Melbourne University. A key focus is placed on the influence Archbishop Daniel Mannix exercised on the young Santamaria including persuading him on the day that he was admitted as a solicitor into accepting a two year position working for the Australasian National Secretariat of Catholic Action (ANSCA) rather than pursuing a legal career.

This initial commitment marked the beginning of a lifelong vocation advocating causes associated with the Catholic Church and a permanent rejection of a legal career. The profound influence that Mannix had on Santamaria was made clear in an interview in which Santamaria declared that ‘without any doubt, he was the greatest man I’ve ever met’.

A famous debate at Melbourne University involving Santamaria arguing in favour of the proposition ‘That the Spanish Government is the Ruin of Spain’ is also covered. It was a debate that had a major impact on the hundreds of individuals who attended including the famous historian, Manning Clark, who in recalling the debate many years later remarked that ‘[f]rom that night to the present day I will never be able to decide which side I am on – the side of Catholic Truth, or the side of the Enlightenment’.

It would be no surprise to anyone with an understanding of the life of Santamaria to learn that a central focus of the biography is on his involvement in organising and leading the Catholic response to the Communist infiltration of the unions. There is a detailed discussion of the contribution of Santamaria through his leadership roles in ANSCA and the Catholic Social Studies Movement (commonly referred to as ‘The Movement’) to resisting the Communists. Unfortunately for Santamaria and his allies, their work with the Movement created many enemies including the Labor opposition leader, Bert Evatt, who after the election loss in 1954 claimed to be the victim of a conspiracy involving members of the Movement.

Evatt’s public denunciation of members of the Movement and their associates in the Labor Party marked the beginning of a series of events that ultimately resulted in the Labor Party splitting with the formation of a breakaway party that became the Democratic Labor Party (DLP). Although the DLP failed in its ultimate aim of re-unification with a reformed Labor party it had some important policy successes especially in helping win the long battle to secure government funding for Catholic schools.

Attention is also given to the internal Church conflicts that occurred around the time of the Labor split over the appropriate control the bishops should have over the activities of the Movement. The conflict eventually reached Rome and was settled in a way that was unfavourable to Santamaria. His response was to establish a new organisation, the National Civic Council, independent of the Catholic hierarchy to continue the work of the Movement.

Many other aspects of Santamaria’s life are examined in the biography including his critical stance towards both Communism and capitalism, his attempt to establish a new political party in the 1990s led by Malcolm Fraser, the many organisations that he helped to establish, and his influence on future leaders including Prime Minister Tony Abbott who referred to Santamaria ‘as my earliest political mentor, and, with the possible exception of [John Howard], as my greatest mentor’.

The contribution Santamaria made as a journalist is addressed, especially his role as a presenter of Point of View, which became one of the longest running television series in Australian history with more than 1300 episodes produced over a period of three decades.

Santamaria’s love of Australian Football especially his lifelong commitment to the Carlton Football Club is also covered. Although this commitment was tested when an infuriated Santamaria made a short lived promise to cancel his membership with Carlton after they agreed to wear a light-blue jumper instead of the normal guernsey to market chocolate confectionery.

Despite this incident, he remained a member of the club and his loyalty was honoured by Carlton footballers wearing black armbands in their first game after his death in 1998.

This detailed biography is an important contribution to the ongoing interest in BA Santamaria.

The book is in no way a hagiography and includes significant criticisms about his conduct from an extensive range of individuals including the author.

However, Gerard Henderson clearly aims to provide a balanced assessment of Santamaria and a substantial part of the biography includes comments from his supporters praising his political and religious achievements. Anyone interested in developing a better understanding of the life and impact of Santamaria would be wise to include this authoritative biography on the list of texts to consult.

Santamaria: A Most Unusual Man by Gerard Henderson is published by The Miegunyah Press.