Dear Father, I have heard that where euthanasia is legal some health insurance companies are refusing to pay for expensive treatments like chemotherapy, and will only pay for assisted dying. This sounds horrific. Is it true?

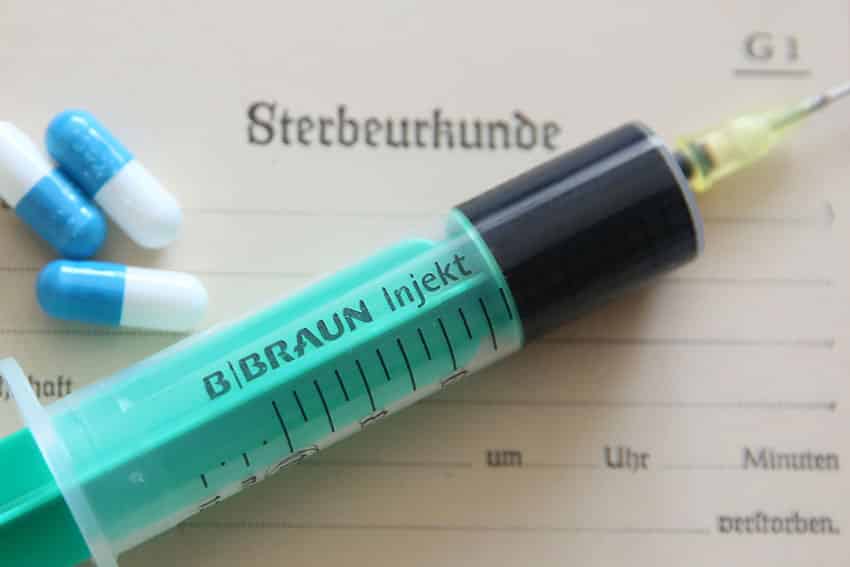

You highlight one of the many reasons why euthanasia, or voluntary assisted dying, as it is often euphemistically called, should not be legalised. And you are right, some health insurance companies are doing exactly what you say. Let me give you one example.

In 2015, just weeks after California legalised physician-assisted suicide, 29-year-old Stephanie Packer, suffering from terminal Scleroderma, was informed by her insurance company that they would not pay for the chemotherapy she needed, but would only make a $1.20 co-payment for life-ending drugs.

If we consider that insurance companies are not philanthropic organisations dedicated to helping people in need, but rather businesses which exist to make money while providing health care, that decision made sense.

Always looking for ways to contain their costs, it also made lots of cents for the insurance company. Stephanie had been told that she had three years to live, so perhaps the insurance company was daunted by the prospect of funding her treatment for that long.

“If VAD is legalised and, all the more, if insurance companies refuse to pay for expensive treatment, there will be many people who will choose to die prematurely …”

In any case, without their help, four years later she was still alive, defying the predictions of medical specialists.

Most voluntary assisted dying (VAD) laws require that, in the judgment of two medical specialists, the person must have less than six months, or sometimes a year, to live. We all know that that judgment in many cases is no more than guesswork.

I suspect you, like me, know a good number of terminally ill people who were given only months to live and who were still alive years later.

In some cases they recovered, or went into remission, and lived a normal life for decades.

If VAD is legalised and, all the more, if insurance companies refuse to pay for expensive treatment, there will be many people who will choose to die prematurely and unnecessarily, when they might have lived for many more years. This is tragic.

What is more, VAD legislation selectively hurts the poor. Those with financial means usually have health insurance which may pay for their treatment, or they can afford to pay for it themselves.

Hence they will be more likely to draw on those resources in order to live longer, and sometimes they will recover completely. But those with fewer means cannot afford to do this. The cheapest, and sometimes the only, alternative is to choose to die. This is very sad.

But the financial pressure to choose death rather than life can come not only from insurance companies. It can come too from family members and others who stand to benefit from the inheritance they will receive from the dying person.

The longer that person lives, the more money that will be spent on their treatment and their hospitalisation or nursing home care. Family members then see their own inheritance gradually dwindling away and they may be moved, out of “compassion” of course, to suggest to their relative to end their suffering by choosing VAD.

The ones that will be particularly vulnerable in this situation are those with disabilities, the mentally ill, the elderly and the poor, especially if their family members see them as a financial burden.

“A 2015 report from the Oregon Health Department revealed that the percentage of Oregon deaths attributed to a patient’s reluctance to “burden” their families had risen from 12% in 1998 to 40% in 2014 …”

It can also be the sick persons themselves who see the financial and human burden they are placing on their relatives by staying alive, and who therefore choose to “do the right thing” and end their life.

The phrase “do the right thing” is used in this country to refer to tossing your rubbish in the bin. To apply it to human beings is absolutely abhorrent. Yet, without necessarily using those words, this is what is happening.

A 2015 report from the Oregon Health Department revealed that the percentage of Oregon deaths attributed to a patient’s reluctance to “burden” their families had risen from 12% in 1998 to 40% in 2014, essentially making the right to die option for some vulnerable people more like a duty to die.

The lethal drugs used for VAD normally cost less than $100, making VAD the cheapest “treatment option” and one that also saves insurance companies money.

This is not the most important reason for rejecting VAD legislation, but it should not be overlooked. Such legislation leads us into uncharted and very dangerous waters.

Related Articles: