Dear Father, I was born in Africa and migrated to Australia with my family many years ago. I am appalled by the big push for euthanasia in Australia. Where I come from we wouldn’t think of ending anyone’s life by this means. Why is there so much demand for it here?

You raise a very important question, one that I too have wondered about for a long time.

Australia, like other countries of the “first world”, has great prosperity and a well-developed health system, with excellent hospitals and good palliative care.

One would think that in a country like ours we would not need, or want, euthanasia, since we can help people die with a minimum of pain and discomfort.

At the same time, we might logically think that in countries, perhaps like your own, where the health system and palliative care are not so well developed, there would be a big push for euthanasia. The opposite is true.

“Do we really need to legalise assisted suicide, as it is called in the laws of some countries? We deplore suicide and yet we want to legalise it for certain suffering people.”

The push for euthanasia comes from wealthy countries, not poor ones. In fact, it comes from very few countries.

We might think here in New South Wales, where we are the only state in Australia not to have legalised it, that euthanasia is a reality practically everywhere in the developed world. That is not so.

Euthanasia is legal in only ten of the 195 countries recognised by the UN: Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, a few states in the U.S. and all states in Australia except New South Wales. The immense majority of the countries of the world do not have it.

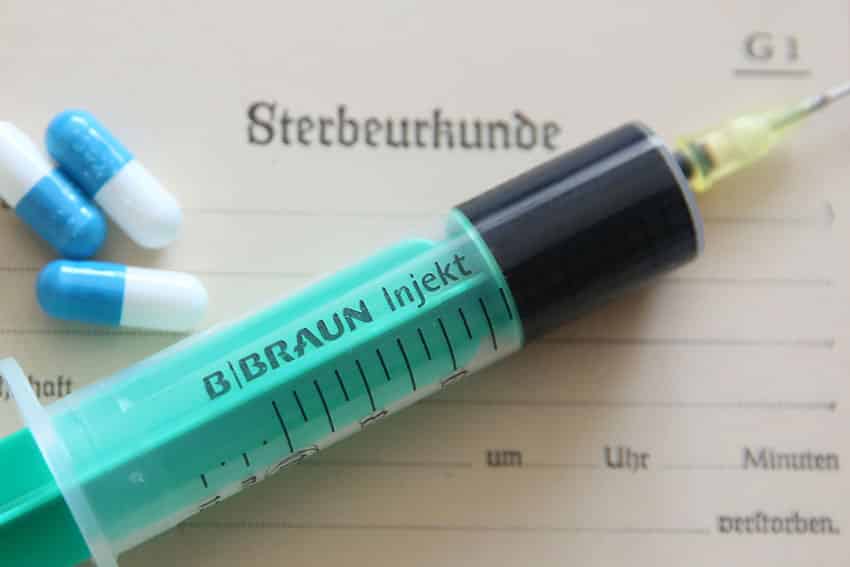

This has to tell us something. Do we really need to legalise assisted suicide, as it is called in the laws of some countries? We deplore suicide and yet we want to legalise it for certain suffering people.

In so doing we are making a distinction between people whose lives are “worth living”, who therefore should not commit suicide, and others whose lives are “not worth living”, who may.

On that basis, the fundamental principle of a democracy that all are equal before the law is not respected. Incidentally, it was in part for that reason that the British House of Lords rejected the legalisation of euthanasia in the 1990s. All lives are worth living. Suffering is part and parcel of the life of man on earth. We all have it in varying degrees and at different times.

As we see in the list of countries where euthanasia is legal, there is not one African or Asian country.

In view of this Pope St John Paul’s observation in his encyclical Evangelium vitae is very relevant: “Here we are faced with one of the more alarming symptoms of the ‘culture of death’, which is advancing above all in prosperous societies, marked by an attitude of excessive preoccupation with efficiency and which sees the growing number of elderly and disabled people as intolerable and too burdensome” (EV 64).

I think we would agree that in a prosperous country like ours, many people can tend to see the sick, the elderly and people with disabilities as a burden, as a threat to their comfort and desire to get on with life.

We are not used to seeing suffering and we would prefer not to have to deal with it. If we legalise euthanasia and suffering people die, it is easier for us.

“What suffering people most want is good care from medical staff, as well as compassion, love, and the presence of their loved ones, not a quick end to their suffering.”

When a good friend of mine in Melbourne was dying of cancer some years ago, his wife told me that several younger women had asked her if she was going to have her husband “put away”. She loved her husband, visited him everyday and had no such thoughts. She said these young women were all well-to-do and “just selfish”. Perhaps so.

Another comment on this comes from Dr Brian Pollard, who established the first palliative care unit in New South Wales and wrote two books on euthanasia.

He said that in all his years giving palliative care to dying people he had never had a request for euthanasia from a patient. He did have requests from family members who, he says, seemed to be saying, “Could you please put him/her out of our misery?”

What suffering people most want is good care from medical staff, as well as compassion, love, and the presence of their loved ones, not a quick end to their suffering.

As St John Paul II put it: “True ‘compassion’ leads to sharing another’s pain; it does not kill the person whose suffering we cannot bear” (EV 66). If we were more compassionate and generous, we would not need or want euthanasia.

Related Articles: