In his message for World Communications Day this year, Pope Francis wrote about ‘fake news,’ defining it as “the spreading of disinformation online or in the traditional media… based on non-existent or distorted data meant to deceive and manipulate the reader.”

I don’t really love the phrase; maybe because I associate it more with US President Donald Trump trying to deflect any public criticism than anything else, but the phrase came to mind this week when thinking about a recent story in Fairfax media about Bishop Gerard Hanna, bishop emeritus of the Diocese of Wagga Wagga, and his involvement with the case of John Joseph Farrell, a former priest currently in prison serving a 29-year sentence for child sexual abuse.

The article said that Bishop Hanna had been “harbouring a secret” about his role in the cover-up around Farrell. It reported that Bishop Hanna had taken Farrell into his parish after he was kicked out of another, and paid for his legal defence with church money. Making no attempt at subtlety, the article posed the question: “Should bishops complicit in cover-ups be held to account for their past actions?”

If that was the only information you had about Farrell and Bishop Hanna, it would look pretty bad. And unfortunately, there is only limited information available. The Whitlam Report, a 2012 inquiry into the Farrell case conducted by former Federal Court judge Antony Whitlam QC at the request of the Dioceses of Armidale and Parramatta, is available online, but the Royal Commission has not published its report into the Farrell case study, and its website no longer holds the transcripts of its public hearings.

This means that unless they were prepared to dig, the interested reader would not be able to get much more information than what Fairfax reported. And there is much more to the story. Ironically, the journalist left so much out of an article that was titled ‘The Bishop, the priest and the sins of omission.’

I want to fill the gap and provide some of the detail that was outlined in the Whitlam Report and the relevant Royal Commission transcript.

The picture painted of Bishop Gerard Hanna’s involvement in the Farrell case in these two documents is very different to the one in Fairfax. These documents show him as expressing opposition to Farrell, even prior to ordination.

The Bishop of Armidale in the 1980s was Bishop Henry Kennedy (not to be confused with Armidale’s current bishop, Bishop Michael Kennedy.) The seminary at which Farrell had been studying had not recommended Farrell’s ordination. Bishop Hanna, then a priest of the Diocese of Armidale and one of the members of its Council of Priests, told Bishop Henry that if the seminary recommended against ordaining Farrell, then Farrell should not be ordained. Bishop Henry ordained him anyway.

Farrell’s first appointment was to a parish at Moree. There was at least one allegation of child sexual abuse against him there, and so he was placed on “sick leave” – a euphemism sometimes used to cover up the real reason for his removal. Because no charges had been laid against Farrell, after two months, Bishop Henry decided to appoint Farrell to the parish at East Tamworth, where then-Father Hanna was the administrator.

Father Hanna told Bishop Henry that two months was not long enough to give people to come forward with complaints, and argued that more time was needed. Bishop Henry placed Farrell into the East Tamworth parish, asking Father Hanna to keep a close watch on him and to restrict his duties.

Father Hanna did just that. He told Farrell directly that he knew of the allegations, and was placing him on restricted duties: no school visits, no school Masses, and no mixing with altar boys. Father Hanna told the other assistant priest at the parish, the school principals of the local schools, and a nun who helped with the altar boys about the allegations and the restrictions on Farrell. When he noticed Farrell spending a fair amount of time with a particular family, Father Hanna also informed that family of the allegations against Farrell.

The restrictions placed on Farrell were such that the psychologist who was treating him commented that the lack of trust shown by Father Hanna was causing Farrell great stress. But it seems to have been effective, because Farrell is not believed to have offended during his time under Father Hanna’s supervision.

After Farrell was arrested and charged, Father Hanna did not have the ability to suspend his faculties, but stood him down from any ministry in the parish. And while he did call the diocese’s lawyers when Farrell was arrested, Bishop Hanna told the Royal Commission that he did not pay the legal bill, but rather forwarded it to the diocese for payment.

When the court decided that the charges against Farrell could not proceed because of a lack of evidence, Father Hanna wrote to Bishop Henry and expressed his view that, because this was not the same as a ‘not guilty’ verdict, Farrell should not be returned to ministry. Farrell did end up in ministry, in the Parramatta diocese, before finally being removed from ministry altogether, being laicised and – ultimately – imprisoned.

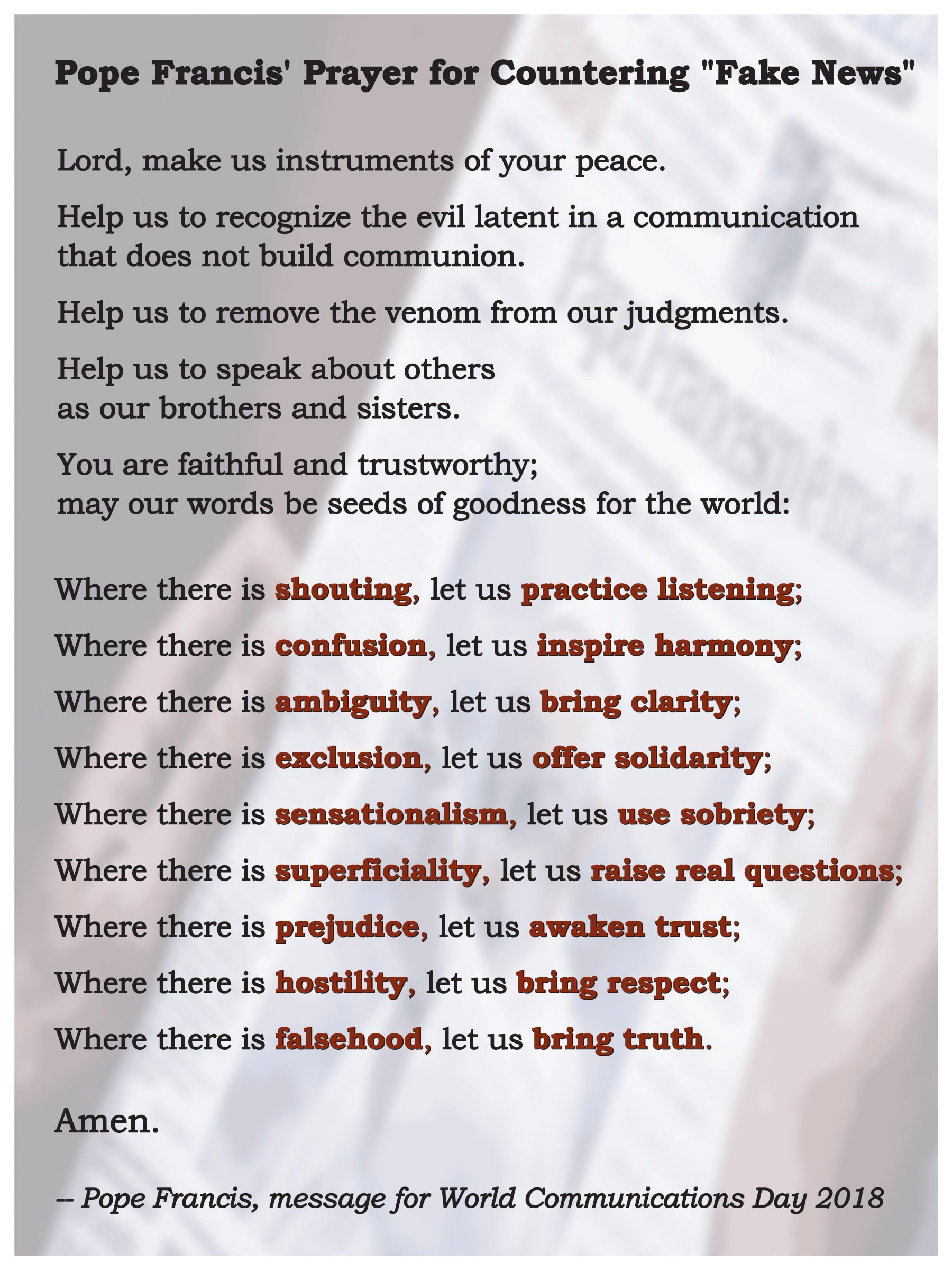

It is unclear why none of these facts appeared in the Fairfax article, which, while mentioning the Whitlam Report, failed to mention that Whitlam concluded it to be ‘fortuitous’ that Farrell was placed with Father Hanna because of the supervision he provided. I don’t want to speculate. The only answer, I believe, to ‘fake news’ is to use whatever platform we have to tell the truth.