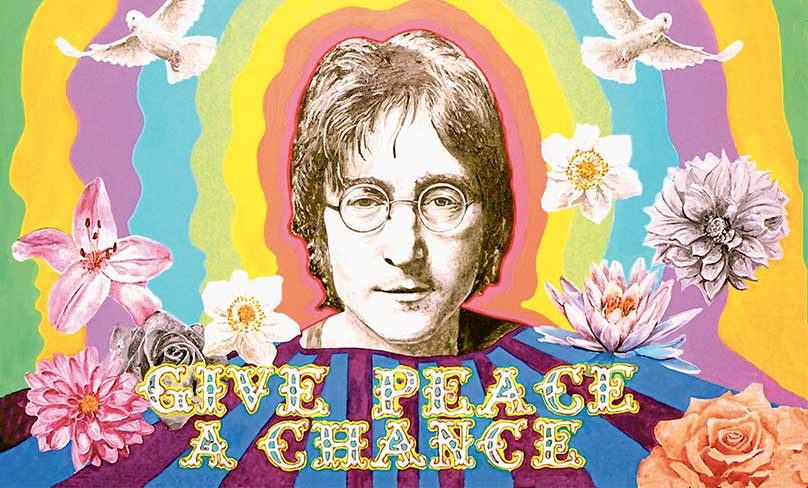

“Imagine there’s no heaven; it’s easy if you try. No hell below us; above us only sky.” So begins John Lennon’s famous Imagine anthem.

I have had this song in my head for the past few days. It found its way in there after a conversation with someone about last week’s article on Tasmania’s latest attempt to become Australia’s first genderless state.

Since penning that piece, the Northern Territory passed legislation allowing a change to sex or gender identity with the simple filing of a form.

We were discussing what possesses people to define their own gender, or choose from a pre-prepared list of 33 or more options such as omnigender, neutrois and demigender, and also what type of government or prospective government would think it wise to change the laws to give credence to such insanity.

It was during this conversation that Imagine found its way into my head. It seems to me that in many ways, we are now living in the so-called utopian society described in Lennon’s great hit.

“Imagine there’s no countries; it isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for; and no religion too.”

What Lennon is describing is the post-Christian society that many western democracies appear to be pursuing. He surmised that if we removed faith and nationality, then humanity would unite and live in peace.

But Lennon missed one key idea.

If we removed the existence of heaven and hell, and of any notion of God, faith or religion, then yes, there would be nothing (or very little) to kill or die for. Lennon’s understanding of humanity was correct in this respect.

But it was also incomplete, because logically, if there is nothing to kill or die for, then there is also nothing to live for. Human beings, by our very nature, are religious. We instinctively understand that there is something greater than ourselves, and go in search of it. This search has sustained humanity throughout history.

If we had no relationship with God, and if there was no promise of heaven, then for what or for whom would we live? If we lived only for today, then what motivation would there be for us to choose good over evil, particularly where doing evil could afford us some short-term pleasure or gain?

Instead of uniting the world in peace, removing faith and nationality seems to have caused a pervasive identity crisis throughout the western world.

More than any time than I can remember, people are desperately attempting to define themselves. Take just three of the 33 genders referred to above as an example.

Pangender, it is said, refers to “a person who identifies as more than one gender,” poligender translates to ‘many genders’ and refers to “a person who identifies as more than one gender,” while omnigender translates to ‘all genders’ and refers to “a person who identifies as more than one gender.” What the difference between the three descriptors are is anyone’s guess. It is a whole new language that is utterly devoid of any meaning.

But the gender fluidity nonsense is a symptom, not a cause, of this crisis. The cause is a culture that tells people that there is no meaning to their lives; that there is no greater reality beyond themselves.

It is evident not only in the identity crisis affecting individuals, but at a macro level as well, in our elected officials. How many politicians in Australia and overseas not only lack the courage of their convictions, but appear to lack courage and conviction as well? How many, like the world which Lennon describes, have nothing to kill or die for? Nothing for which they would even risk a handful of votes, let alone their lives?

The removal of religious faith does not unite people in peace; it denies humanity the ability to marvel at something truly great, and to strive for greatness themselves. Searching for the infinite in finite human beings is never going to satisfy the human hunger for meaning, and this hunger manifests in the identity crisis we now see. It’s why people are pushing for changes to laws that would allow them to declare their gender identity, and to force other people into affirming them in the same.

While we must continue to do what we can to fight back against these laws, doing so would only be addressing the symptom of the problem. To counteract the root cause, particularly amongst our younger generations who are bombarded with messages about self-creation, is to reiterate to them that their first – and most important – identity is as a beloved child of God. Hopefully with that solid foundation, they will not be looking for identity elsewhere.