Last time, in this space, I talked about the idea of docility to the Church’s teaching, dogmatic or not. The basic point was simply that we should do as the Church calls us do even when the Church does not bind us under pain of heresy or schism (which is to say, virtually always).

Of course, the obvious reply to this is, “Even when the Church calls us to not report the rape of our child by a priest?”

It’s a perfectly reasonable question. And the obvious answer is “Of course not.” Nobody, not even the Pope can compel us to do evil. Nor can anybody, even the Pope, command us to let evil happen by our inaction. This is what the Church means by the real idea of primacy of conscience. We must do what we know—really know—to be the right thing no matter what. So if, God forbid, somebody is sexually assaulted by a priest, it is vital that it be reported to the cops and the culprit called to account.

What then of the docility I was speaking about last week? Am I not contradicting myself? No, because docility means docility to the Tradition the Magisterium articulates, not to every single thing to come out of a bishop’s or priest’s mouth. When the Church says something like, “The gospel tells us to welcome the stranger” and then says “A reasonable application of that is to not cage children at the border” this is indeed an obvious extrapolation from the gospel. When a priest or bishop tells a victim of rape to keep their mouth shut and not call the cops, this is an obvious violation of the gospel which calls us to protect the least of these. The cleric who does this is not living according to the Tradition but in direct contradiction to it. And it falls to us to obey the gospel, not the cleric, in such a case.

Learning to make such distinctions is a problem as old as the gospel and it is why it behooves each of us to learn the Tradition so that we can obey the Magisterium and discern how to live with true prudence.

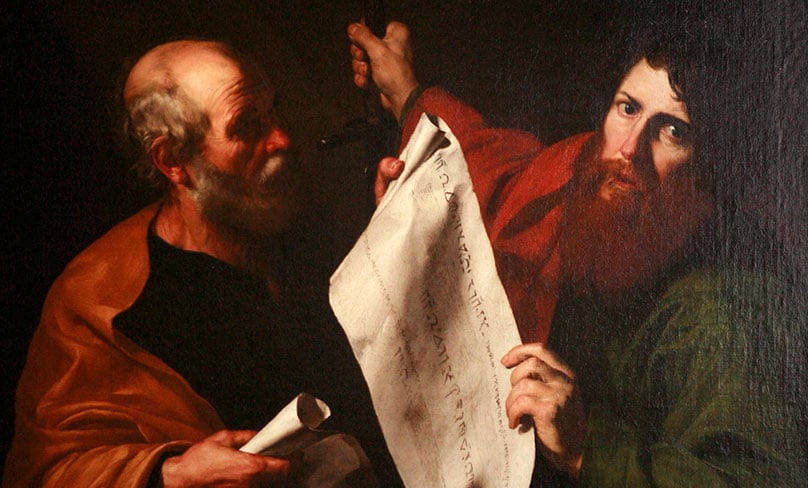

One of the curious realities of the gospel is that it is, as Paul says, a treasure hidden in jars of clay (2 Cor 4:7). The Holy Spirit, not we, is the soul of the Church, guiding it and, as we make our often dunderheaded decisions, writing straight with crooked lines. Peter seems to have been chosen, in no small part, to illustrate this point. So, for instance, we see him in Matthew 16, speaking under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit with the clear perception that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. Jesus himself tells Peter that he did not figure this out on his own but that the Father had revealed it to him. Two minutes later, we find Peter trying to boss Jesus around and tell him he cannot go to Jerusalem and be crucified. Jesus must rebuke him and call him “Satan” to shut him down for thinking not as God thinks but as men think.

Later, in Acts 15, we find Peter again speaking in the Council of Jerusalem and declaring, under the inspiration of the Spirit, that we are saved by grace through faith in Christ and not by works of the law, meaning that Gentiles can become disciples of Jesus and members of the Church without keeping such Jewish customs as circumcision or eating kosher. It is the first and most significant development of doctrine in the entire first century, since it freed the Church from the matrix of its Jewish cultural origins and allowed it to evangelize the Gentile world.

But when the Council ends and Peter goes to Antioch, he forgets the teaching he himself articulated by the Holy Spirit and starts to avoid eating with Gentile believers out of fear of Jewish believers judging him unclean and defiled. Paul (as he tells us in Galatians 2) has to chew Peter out for forgetting the meaning of the gospel Peter himself had preached.

Catholics are quite capable of imitating Peter in all this, including bishops—indeed, especially bishops. For what happens from time to time in the history of the Church is that the Church meets in Council and, again under the guidance of the Spirit, is enabled to articulate some insight into the Tradition which it then promulgates in its formal teaching. But then, just like with Peter, the council ends and the bishops go back to just being the ordinary schlemiels they are. And very often, just like with Peter, they lack the wits or the nerve or both to live out the teaching they themselves have articulated.

So, for instance, at the Council of Nicaea, the Church formulated the doctrine of the Trinity. But after the Council, the bishops, including some popes, then spent about forty years dithering about actually sticking with the teaching of the Council. The Imperial Court, in particular, preferred a compromise position called “Semi-Arianism” and lots of bishops were willing to go along. It reached a point, forty years later, where (as St. Jerome put it) “the whole world groaned and marvelled to find itself Arian.” Some hard-noses like Athanasius spent their episcopal careers getting exiled from their own dioceses five times, plus getting accused of murder and so forth, merely for standing for what Nicaea had taught while in some areas the majority of bishops went for weak tea compromise. Why? Because, merely when acting on their own, it is quite possible for bishops to chicken out on, forget, or misunderstand the Tradition they themselves have taught.

Take Gaudium et Spes, a document I regard as expressing perhaps the single most important development of doctrine of the Second Vatican Council. Hear this thunderbolt:

“Indeed, the Lord Jesus, when He prayed to the Father, “that all may be one. . . as we are one” (John 17:21-22) opened up vistas closed to human reason, for He implied a certain likeness between the union of the divine Persons, and the unity of God’s sons in truth and charity. This likeness reveals that man, who is the only creature on earth which God willed for itself, cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself.”

“[M]an… is the only creature on earth which God willed for itself.” That staggering insight is as old as Genesis. But under the lash of the horrors of the 20th century, the Church was driven by the Holy Spirit to articulate the truth in a profound new way. It means that there is nothing on earth to which human beings are the means to some other end. Not the economy. Not the state. Not science. Not some philosophy. Not the breeding of a better race. Not anything.

And not even the Church. Human beings are made in the image and likeness of God and their dignity cannot be subordinated to any earthly thing, and still less to the cover-up of sin for the sake of that earthly thing. So we cannot crush human dignity under the wheels of the triumph of Communism or the exaltation of Capitalism. We cannot smash the dignity of the human person under the banner of America or Russia. We cannot use humans as lab rats for the good of Science.

And we cannot tell the victims of priestly abuse to be silent “for the good of the Church”. People are not made for the Church’s bureaucracy. The Church is made for them and for their good since it is in them that Christ dwells as in the Tabernacle.

This was the epic failure of the bishops: not that they taught wrongly in Gaudium et Spes, but that they failed to grasp what they themselves taught just like Peter did at Antioch. It is not that the episcopacy was more monstrously wicked than other institutions. It’s that they were exactly like other institutions. They behaved with the same selfish, blind, worldly, earthly stupidity as any other human institution from the US Department of Education to the corporate suits in Harvey Weinstein’s Hollywood. They forgot that each member of their flock were the only creatures on earth God has willed for their own sakes and instead acted like every other bureaucratic functionary, imagining that every member of their flock existed only to service the machinery of the bureaucratic institution that had become an idol for them.

When such things happen in the life of the Church—when clergy ask us to do or to neglect evil, then so far as lies within our power we have an obligation to say, “We must obey God rather than men.”