When the Catholic judge, Amy Coney Barrett, was appointed to the US Supreme Court, it brought to light two distinctly different friendships.

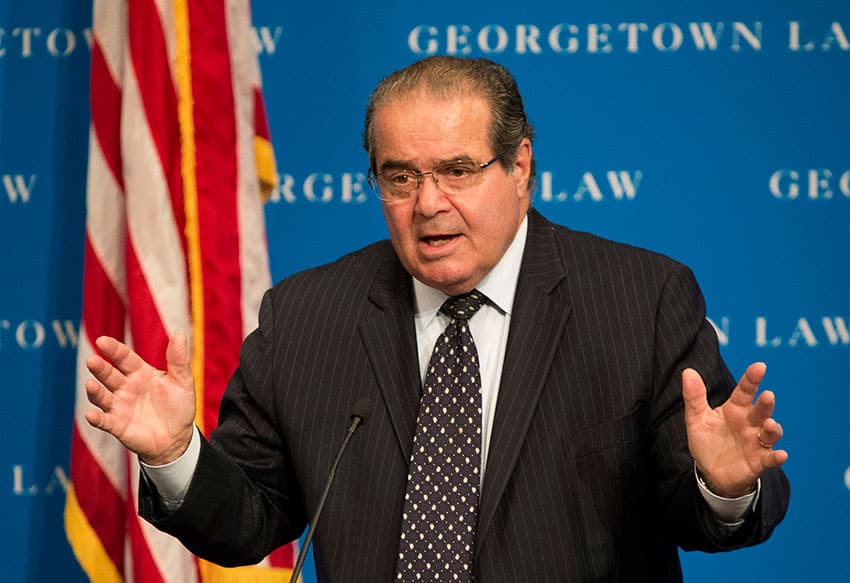

One was between Barrett and a late Justice of the Court, Antonin Scalia, a fellow Catholic of serious belief and practice. Barrett was mentored by Scalia during her time as law clerk, and she is expected to be faithful to his legacy of constitutional interpretation in her new role.

But a more surprising friendship was that between Scalia and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a secular Jew, who died last September and whom Barrett succeeded on the Supreme Court. Their friendship rested on a deep divergence of worldviews. While they differed markedly on legal judgments, they maintained a relationship of respect and camaraderie.

Such a blend of unity and division is a timely message at Christmas, for the birth of our Saviour was attended by both these elements. On the one hand, we know the profound harmony of the Holy Family, reflected in Mary and Joseph preparing for and protecting the Child Jesus. On the other, we shudder at the surrounding social and political discord which led them to flee to Egypt so as to escape Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents.

Scalia and Ginsberg differed fundamentally on the subject of abortion. Scalia was dedicated to his Catholic belief in the sanctity of unborn life, while Ginsberg championed abortion as a woman’s right. Despite such disagreements, they were close friends, sharing various interests and enjoying the company of each other’s family.

After Ginsburg’s death, Scalia’s son Eugene commented on the nature of their friendship:

“What we can learn from the Justices – beyond how to be a friend – is how to welcome debate and differences. The two Justices had central roles in addressing some of the most divisive issues of the day, including cases on abortion, same-sex marriage and who would be President. Not for a moment did one think the other should be condemned or ostracised.

Friendship sealed by debates

“More than that, they believed that what they were doing – arriving at their own opinions thoughtfully and advancing them vigorously – was essential to the national good. With less debate, their friendship would have been diminished, and so, they believed, would our democracy.”

Such friendships are much less likely in present-day society. The polarising nature of social and political movements, such as the so-called “cancel culture”, is banishing the freedom to form friendships in the midst of disagreements. It is now hard to argue on key social and political issues without the exchange becoming derailed by personal abuse. Intellectual judgments (“I think what you say is untrue”) are being swamped by moral pronouncements (“I think you are an evil person”).

No longer does the English author Sir Arnold Lunn’s definition of the “true liberal” apply, as someone “who protests against the persecution of conservatives;” nor the comment of the late Labor parliamentarian, Fred Daly, who never made an enemy he could not be friends with.

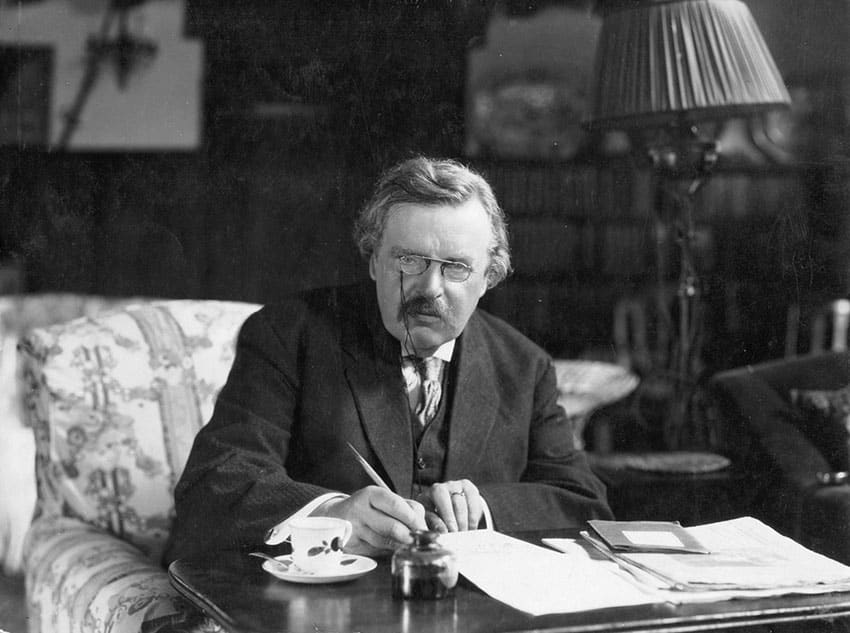

G.K. Chesterton used to caution against allowing an argument to degenerate into a quarrel. The purpose of an argument is to clarify the truth, and when a quarrel intervenes, it blocks the opportunity for enlightenment. “Perhaps the principal objection to a quarrel,” as Chesterton put it in a typical paradox, “is that it interrupts an argument.” In his autobiography, he reflected on his relationship with his younger brother Cecil. “I am glad to think,” he wrote, “that through all those years we never stopped arguing; and we never once quarrelled.”

Chesterton won praise for his lifelong friendships with public figures whose views he opposed. Perhaps the most notable was the playwright and social critic, George Bernard Shaw. “I have argued with him,” said Chesterton, “on almost every subject in the world; and we have always been on opposite sides, without affectation or animosity. . . . It is necessary to disagree with him as much as I do, in order to admire him as I do; and I am proud of him as a foe even more than as a friend.”

Chesterton defended such causes as the natural family, the independence of private property, and a patriotic love of one’s nation, against Shaw’s preference for the power of the State, international government, and the evolution of a superior humanity. Throughout these endless disagreements, they remained devoted friends. Chesterton praised Shaw for his “fair-mindedness and intellectual geniality”, while Shaw, who was personally wealthy, gave practical help by sponsoring public debates when Chesterton was financially strapped.

Affinity transcends arguments

A further clue to their friendship is that Chesterton may have sensed in Shaw an unfulfilled search – that beneath his disdain of religious faith lay a deep spiritual yearning, as revealed in the letters he exchanged with an enclosed Benedictine nun, Dame Laurentia McLachlan, of Stanbrook Abbey.

“When we are next touring in your neighbourhood,” Shaw once wrote to her, “I shall again shake your bars and look longingly at the freedom on the other side of them.” (In a Great Tradition, 1956)

This may be part of the secret of a friendship founded on differences – that one person can sense in the other a hidden need that only friendship can begin to satisfy. A spiritual affinity is struck, which becomes the means of deepening a friendship, and leading, not just to communication, but to communion. The result is not to dispel disagreements so much as transcend them.

In our yearly calendar Christmas remains a unique feast when friendship can triumph over differences. Even in its present de-Christianised form – and despite the disconnecting impact of the coronavirus – it is a time when next-door neighbours are more likely to be neighbourly, the lonely and the isolated more likely to be visited, and difficult family members more likely to be reconciled.

We gaze at the Christ Child in the crib and cherish the Holy Family as the most sublime model of friendship. We acknowledge its incarnational power and grace, and strive to extend the divine harmony of Jesus, Mary and Joseph to our own family and all those to whom we should reach out.

Related