St Lydwine of Schiedam

Question: A friend of mine who is very sick has been praying to St Lydwine of Schiedam. I never heard of her. Who was she?

St Lydwine (1380-1433) was a Dutch saint who was very sick, more sick than can be imagined, as we shall see. If her suffering seems too great to be real, it is well documented. The mayor and other authorities of Schiedam issued a formal declaration in 1421 detailing many of her ailments, and biographies were written by people who were very close to her, one of them by her confessor and another edited by Thomas à Kempis, a contemporary of hers. I will draw largely on the work of à Kempis in what follows.

Lydwine, or Lydia, was the fifth child, and the only girl of the nine children of Peter and Petronilla, of Schiedam in the Netherlands. Having gone to Palm Sunday Mass in the local church, Petronilla rushed home to give birth to Lydwine while the Passion was being sung, an omen of the suffering Lydwine was to endure. The family was poor and Peter worked as a night watchman over the city to support his family.

She was a beautiful and intelligent girl

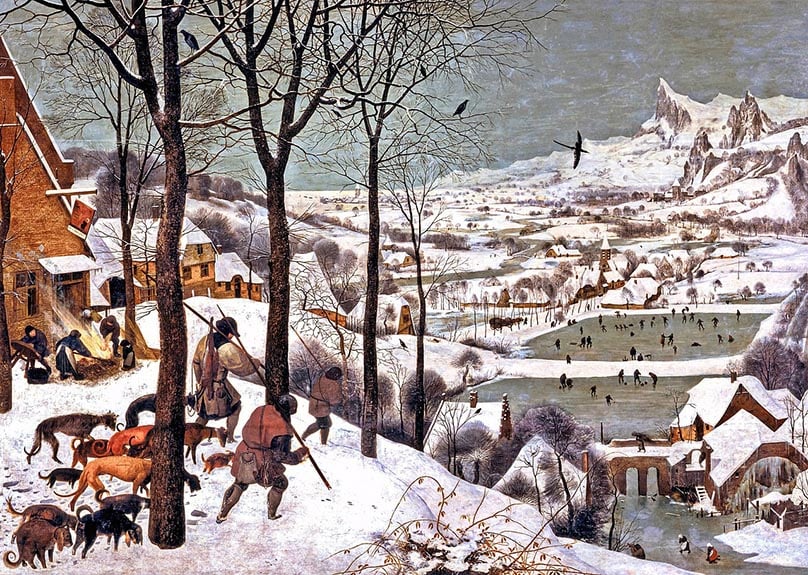

At the age of seven or eight, Lydwine already had great devotion to the image of Our Lady in the church of Schiedam. She was a beautiful and intelligent girl. When she was twelve many men wanted to marry her, but she declared her intention to remain a virgin. Early in her fifteenth year she became very sick but recovered at least partially. Later that year, while ice skating with friends, someone bumped into her, throwing her onto the ice. She suffered a broken rib on her right side, developing into an abscess which gave her much pain.

Early in her sixteenth year the abscess burst and fluids came up through her mouth with vomiting. From then on she had constant infirmities. Soon she was unable to walk except with a stick or crutch and her body began to waste away.

When she was about eighteen her confessor taught Lydwine how to meditate on the Passion of Christ. She found this very difficult at first, but with persevering effort she acquired great recollection and soon began to feel happiness in her pains, recognising in them God’s will and her special vocation. At the time she was receiving Communion twice a year.

From the age of twenty Lydwine was confined to bed, where she remained until her death at the age of fifty-three. She ate almost nothing except for an occasional piece of apple, a little bread, some milk or wine, a little sugar or grapes. When her body could no longer tolerate even these, she drank only a little water from the Meuse River each week and she survived on the Eucharist. Another of her maladies was that for long periods of time she was completely unable to sleep.

Lydwine had three large open wounds on her body and maggots began to eat into her rotting flesh. The maggots came out of the one in her stomach and so a plaster of fresh wheat and honey was placed over the wound so that the maggots would feed on it rather than on her. The smell given off was surprisingly sweet. At around the age of thirty-two Lydwine vomited small pieces of organs, including bits of her lungs, liver and intestines. During her last years she could not move her limbs except for her head and left arm, and she always lay on her back.

As if this weren’t enough, Lydwine also had intense headaches, toothaches, fevers and dropsy. She could hardly speak because of a cleft in her lower lip and chin. She could not see out of her right eye and her left eye was so weak that it was painful for her to see any light, requiring her to remain in darkness all the time. She accepted all her ailments with great love for God and offered them up for the conversion of sinners and for the souls in purgatory.

Around the age of twenty-five she began to experience ecstasies which continued until her death. She was taken in spirit to purgatory where she saw the suffering of souls, including some of her friends, and she was also given visions of hell and heaven. At around forty she was happy to be able to receive Communion several times a week.

In April, 1433, God finally ended her suffering and took her to heaven. She was canonised by Pope Leo XIII in 1890 and her body lies in the Basilica of St Lydwine in Schiedam.

Related Stories: