Last week in Terre Haute prison, IndiaCatechismna, three men were given lethal injections. Convicted murderers Daniel Lewis Lee, Wesley Ira Purkey and Dustin Lee Honken were the first US federal inmates to be put to death in 17 years.

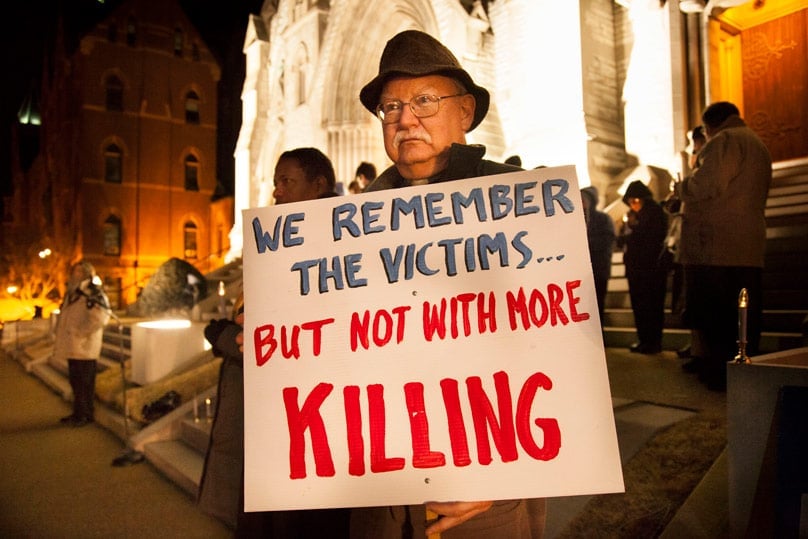

The Trump administration’s resumption of capital punishment in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis has shocked and angered many Americans, including many men and women of faith.

The archbishop of Indianapolis, Charles Thompson, issued a statement a month ago in which he forthrightly condemned the executions that were shortly to take place in his diocese, citing paragraph 2267 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

As revised by Pope Francis in 2018, this paragraph declares that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

Thompson took the term “inadmissible”, in this context, to mean “morally inadmissible,” or intrinsically immoral. This indeed seems to have been Pope Francis’ meaning, given his public statement in October 2017 that the death penalty is “in itself contrary to the Gospel.”

When the revision to paragraph 2267 was first announced, some were quick to decry (or applaud) it as a reversal of Church teaching. Was it so? The resumption of federal executions in the US is an appropriate occasion to reopen this question.

The revision’s prima facie inconsistency with longstanding Catholic teaching is difficult to deny. St Paul says in Romans 13 that secular rulers do not “bear the sword” in vain but are rather ministers of God’s vengeance against wrongdoers, which seems a Scriptural endorsement of capital punishment for at least some crimes. (The sword is, after all, an instrument of violent death.)

Most Church Fathers and scholastics, including St Augustine and St Thomas, approved the death penalty for serious crimes, as did St Alphonsus Liguori, widely considered the Church’s greatest moral theologian. The Roman Catechism and the Catechism of St Pius X both approved it. Numerous popes, including Pope St Pius V and Blessed Pope Pius IX, personally ordered executions.

Archbishop Thompson averred that the 2018 revision to the Catechism was at any rate consistent with the teachings of Francis’ immediate predecessors. Yet this too is questionable. True, both Pope St John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI wished to see an end to the death penalty and urged governments around the world to discontinue it. But John Paul acknowledged in Evangelium Vitae (§56) that, in extremely rare cases, capital punishment might be justified.

The older version of paragraph 2267 of the Catechism accordingly stated that the Church “does not exclude recourse to the death penalty, if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor”. Pope Benedict never expressed any disagreement with this statement, let alone any wish to delete or revise it.

Most Church Fathers and scholastics, including St Augustine and St Thomas, approved the death penalty for serious crimes

St Paul warns that we must not do evil that good may come. If, as per Thompson’s seemingly correct reading of the revised paragraph, capital punishment is intrinsically immoral, it could surely not be justified even in cases when it is the only possible means of defending human lives against unjust aggression. (In a partly similar way, abortion is not justified even in the mercifully rare cases when saving the mother’s life depends on it.)

If capital punishment for even the worst of crimes is “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person,” and hence immoral, it surely follows that intentional killing of any kind, under any circumstances, is immoral. Yet this is not an easy position to sustain.

The chief business of military personnel is the intentional killing of enemy combatants; should Catholics then refuse to serve in the military and demand that their nations’ armed forces be disbanded?

Again, even nations, like Australia, that have abandoned capital punishment still permit police officers to use lethal force in extreme situations, such as the 2014 Lindt Café siege in Sydney. Should this permission be withdrawn? Would this not, in effect, put governments at the mercy of terrorists and armed insurrectionists? The reasoning of the revised paragraph 2267 seems implicitly pacifist, if not anarchist. And whatever one thinks of pacifism and anarchism, neither has any support in the mainstream Catholic tradition.

Inclusion in the Catechism does not guarantee a statement’s infallibility, else the Catechism could never be revised. While Catholics must not lightly refuse their assent to any papal teaching, both the strength of prior magisterial support for capital punishment and the disturbing implications of the revised paragraph 2267 make it at least questionable whether we are bound, on pain of sin, to assent to it.

We may still believe that the death penalty is unnecessary under modern conditions, or objectionable on extrinsic grounds such as the danger of occasional wrongful convictions in capital cases. But let us not be too hasty to condemn it as intrinsically immoral.

Related articles: