When my father died, through all the tears and grief, I remember how dazed my family all were by the number and types of people who came to his requiem. There were many well known faces of course but also those we had never before known.

What came through again and again, were the comments about Dad’s almost gravitational force for hospitality. So many of my contemporaries and cousins told stories of perching at the end of our large creaking table sampling a glass of red (a big boisterous red from Coonawarra or Langhorne Creek if I recall) while my father in turn listened with his pipe in hand or regaled them into laughter.

Then there were the stories of those who never appeared at our table but for whom my father would take his table. Elderly people and those living alone talked of the bags of Dad’s home-grown silver beet or our chooks’ eggs arriving at their door or most delicious of all, one of his massive loaves made with much kneading and pounding amidst clouds of stone-ground flour. My father was something of an artisanal baker before it was hip.

“Bonhomie” (originally French) is a compact notion which captures something of the quality of my father: generous, spontaneous, definite in his convictions but inviting. He took himself, as G.K. Chesterton says the angels do: “lightly” (that is why they can fly quips GKC). We tend not to use bonhomie to describe multifaceted womanly hospitality. The word suggests not merely “attractive blokeyness” but the greater commitment and character of a “good masculinity.”

“Goodness” in this sense is more than a confident self-assertion or natural charm. It seems to require a type of vocation to a virtue which attracts as well as welcomes others, especially the traveller, the stranger or the vulnerable.

In our consumerist culture there is always the risk that hospitality becomes commercialised into “entertainment”; showing off our “shop perfect” array of stuff or our own performances as hosts with the most. It can become a display of perfectionism rather than a sharing of grace and friendship.

Recently, the American Catholic writer, Brandon McKinley has published an insightful article titled: Stop Making Hospitality Complicated

McKinley argues that because of this trend, true home-based hospitality is becoming rare. Everyone in the household, including the parents are too hectic to rise to the occasion.

“Having guests, we feel, means putting on a show; we set up the stage and put on costumes and are the stars of the production. It sounds intimidating and exhausting—because it is. But here’s the thing: Real hospitality—the sharing of everyday life with friends, current and soon-to-be—is even more frightening.”

True hospitality requires both strength and vulnerability.

We naturally associate hospitality with maternal care and feminine “genius”, after all the ultimate form of hospitality is the intimate and costly sharing of a woman’s body with a tiny growing human being. The type of welcome that my father exemplified and initiated, not only to his eleven children but to all comers, is the foundation of a household and an entire ethos.

The ancient Greeks understood something of this when they insisted that there was a civic and moral duty to welcome the stranger, the xenos, who one made first a guest and then a friend. It was an injunction against fear and distrust of the stranger that we call today xenophobia.

In the Bible this type of hospitality is elevated and shown by faithful fathers. Chapter 18 of the Book of Genesis, captures the focussed attention and rush the patriarch Abraham has in readying his household for the mysterious divine visitors at Mamre. Hebrews (13:2) ties this ancient story into the sense of being One Body in Christ: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.”

In the infancy narratives of Christ, Saint Joseph is the heart of hospitality and justice. At the John Paul II Institute, Dr Owen Vyner has noted that Joseph had this faith-filled hospitality to such a degree that he was willing to adopt a divinely conceived stranger as his son, thereby entering Jesus Christ into his name and into the Davidic line. This adoption by Joseph, is a sign our own “adoption” as sons and daughters of the Lord God, and thereby His limitless hospitality.

These early chapters suggest that Joseph, the “just man” offered hospitality to a surprising crew: first the poor shepherd folk but later the exotic travellers from the East. On the flip-side we also see the ugly face of the absence of male hospitality: the fear, greed or negligence of the inn-keeper and the murderous resentful monstrosity of King Herod.

Masculine hospitality has implications for the building up of what we call the “culture of life.” We only need to investigate how often women report seeking out abortions when they sense or fear that their male partners will not welcome them as mothers.

In June 2007 in Paris, the Catholic Church began the process for the beatification and canonisation of Jérôme Lejeune, a man who may well serve as a modern but holy patron of masculine hospitality in this sense.

Servant of God, Jérôme Lejeune, was born in Paris in 1926 and lived and worked for most of his life in that great city. Although he died at the age of 67 from lung cancer, his spirit of paternal hospitality and ethical courage still echo within the Church and the world across so many important domains: science, medicine, law, society and towards the dignity of the disabled.

Professor Lejeune was a geneticist and paediatrician who in 1958 discovered the chromosomal factors for the condition we now know as Down’s Syndrome. Up until that time, the folk wisdom was that the condition was a side-effect of syphilis in the parents. Lejeune also dedicated his work to discovering ways to ameliorate the developmental delays that Down’s and other chromosomally “different” people experience as well as linking the benefits of folic acid in the prevention of such conditions as spina bifida.

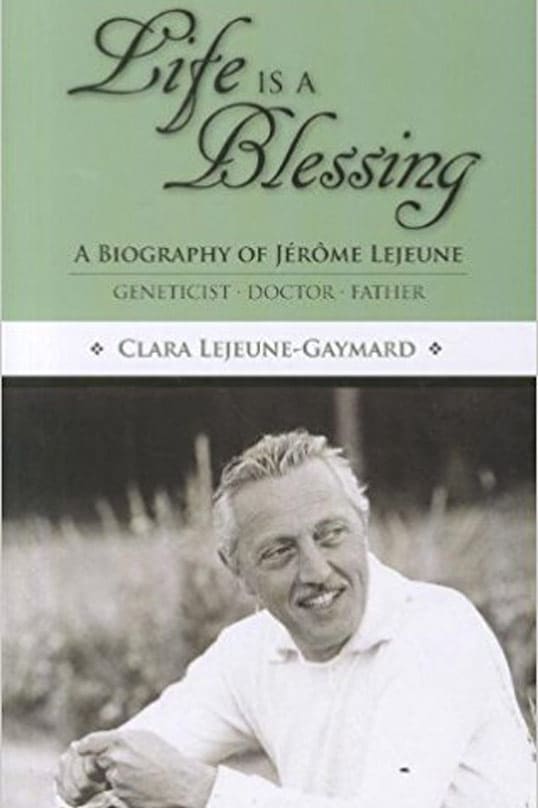

Lejeune’s outstanding scientific work was matched by an even more heroic concern and reception of his Down’s and other patients at both the personal and public level. In her moving biography of her father: Life is a Blessing (2011), Clara Lejeune Gaymard recounts that at any one time her father treated up to 5,000 children with genetic irregularities; nonetheless he remembered each person by his or her first name. He thought of all his patients as his “little ones” and would visit them and their families to support and promote their progress in education and work opportunities and to provide them with low-cost medical support.

Lejeune’s early stardom in the international scientific galaxy was cast into shadow, when he realised to his horror that the very science and research techniques which lead to his discovery of trisomy-21 and other conditions in utero, was being used as a means of prenatal screening and the termination of those affected.

Against much orchestrated protest, the Professor became an articulate and prominent opponent of inter-uterine “search and destroy.” He frequently and publicaly testified that it was the science he had served which provided the evidence for marking the beginning of a human being’s biography as an embryo.

He said prophetically: “For thousands of years, medicine has striven to fight for life and health against disease and death. Any reversal of this order would entirely change medicine itself.”

Pope Saint John Paul II recognised Lejeune’s distinctive apostolate of hospitality and his great commitment to the tandem of ethical and scientific excellence. This matched the central mission of John Paul II’s own pontificate: to defend and expound the dignity of all human beings and to “build up a culture of life.” He called the Professor “my brother Jérôme.” John Paul II would appoint Lejuene as the founding President of his Academy for Life.

While she was in the United States promoting the biography (mentioned above), Clara Gaymard described her extraordinary father’s joyful hospitality several times. Her mother Birthe described to her, a very personal encounter which galvanised Professor Lejeune’s mission of fatherly and medical hospitality and justice.

It involved the visit to his pediatric practice by a weeping ten year-old Down’s boy. Clara recounts how the concerned doctor asked the reason for his tears:

The boy’s “mother said, “He saw the movie (about pre-natal screening) and I couldn’t stop him crying,” … the boy, “jumped in my father’s arms… the boy said:

“You know, they want to kill us. And you have to save us, because we are too weak, and we can’t do anything.” And [my father] came back home for lunch, and he was white, and he said, “If I don’t protect them, I am nothing.” That’s how it started.”