The recent film, Hidden Figures, is based upon a bestseller book (which is more historically consistent), Hidden Figures: The Untold Story of African-American Women Who Helped Win the Space Race by Margot Lee Shetterly, the daughter of an African-American father who worked as a research scientist at NASA.

Hidden Figures, as directed by Theodore Melfi, has all the breezy uplift, humour and stylish costuming you might expect from a classic Hollywood musical. The script compresses historical events and scrambles geographical details and figures into symbolic rather than factual detail. Thankfully, the film transcends its free and easy approach to linear history. (The New Yorker has a very brief overview.)

The three central heroines: Katherine G Johnson, Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughan are based on three actual and admirable women of colour whose remarkable genius for crunching mathematical and theoretical “figures” made significant contributions to the space program of the early 1960s, and for the advancement of both African Americans and women in science well after this.

The performers in the three “hidden figure” parts have rightly received high accolades. The verve and dignity of the women is well portrayed, as is their intellectual brilliance and their fortitude in the face of insurmountable obstacles of segregation and personal hardship.

The backdrop to the film’s action, again only symbolically but effectively conveyed, is the shocking contradiction between the nationalistic ambitions to achieve “scientific excellence” and all that goes with the sleek muted hubris of the modernism of the early 1960s on one hand, and the existence, on the other, of racially segregated buses, wages, schools, work stations, restrooms and water coolers.

Touched upon, in the film’s fast moving scenes and boppy score, are all sorts of other deadly serious issues. The claustrophobia of the Cold War, the dazzled “faith” in unlimited “progress” and the bizarrely domesticated scenes of school time drills in the shadow of nuclear apocalypse.

There is an interesting reflection on the historical details behind the book and film’s accounts by Father James Kurzynski on The Catholic Astronomer page, a Vatican Observatory Foundation Blog.

One interesting theme, touched upon in the film, which seems to be historically accurate, is the unembarrassed recognition of the importance of religious faith in the daily lives of the three women of science. The women are depicted at different times, saying grace before meals, praying with evangelical fervour and attending Church on Sundays and Church picnics afterwards.

Katherine G Johnson, who this year is 99 years old, has been a member of her Carver Presbyterian Church in Virginia for over 50 years. She has been a dedicated and active member of her Church community. John Glenn, the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth, who is played in the film as a boyish charmer (far younger than his real age in life) and who insists that Katherine is the one to double check the “math” of his re-entry trajectory was also a committed Presbyterian. He famously said of the orbital view of his home planet: “Looking at the Earth from this vantage point, looking at this kind of creation and to not believe in God, to me, is impossible. To see (Earth) laid out like that only strengthens my beliefs.”

Dorothy Vaughan, the brilliant mathematician and computer programmer, who died in 2008 (at the age of 98), was the mother of six and an active member of several AME (African Methodist Church) Churches and a member of the Women’s Missionary Society.

This friendly interaction between good science and firm faith, is consistent with the claims of the now deceased Benedictine scientist and philosopher Father Stanley Jaki.

Jaki argues that Christian theology was crucial for the rational origins of scientific exploration and discovery. Faith in turn, inspires the lives, the commitments and moral compass of Christian scientists .

Christopher Kazor, among others, argues that faith and reason are valuable allies in search of the truth.

That set me wondering whether there were Catholic “hidden” women in the male dominated history of science and mathematics.

How many people sitting at their laptops or looking at their smartphones know about the Sister of Charity, Mary Kenneth Keller? Sister Mary Keller was the first American woman (and possibly the first American person) to obtain a PhD in computer science in 1965. An excellent mathematician, she helped to develop the intuitive software language: BASIC.

Fr Jaki uncovered the role of Hélène Duhem, who in the early 20th century, retrieved and promoted the work of her father, Pierre in thermodynamics and the history of science.

Centuries before this, in Northern Italy, and supported by the Pope of the day, Benedict XIV, there were three other remarkable women: Laura Bassi (1711-1778), Anna Morandi (1714-174) and Maria Gaetana Agnesi (1718-1799).

For each of these women, the NASA of their day was the prestigious University of Bologna, then within the Papal States and determined to restore, at the brink of the Enlightenment, its former glory during the High Middle Ages.

Pope Benedict XIV, in fact, urged the University to base its honours on genuine merit and excellence and he insisted that women also be considered by this benchmark. He also encouraged advanced education for women and reformed canon law so that women as well as men could give evidence before the canonical courts in cases of beatification and canonisation.

Laura Maria Catarina Bassi was the first woman to become a physics lecturer in a University. At an early age, her intelligence was encouraged by her father and the family physician to study classical languages and science. She crashed through the curlicued plaster ceiling by becoming a lecturer in anatomy at the University of Bologna at the age of 21. Later she entered the philosophy department. She was the first female member of the Bologna Academy of Sciences. She married a physician, who became her assistant and together they had eight children. When Laura encountered opposition in the university to her presentations, she simply moved her demonstrations in Newtonian physics and optics to her home. The people of Bologna treated her as a star and figurehead for the city. Later in life, Pope Lambertini, Benedict XIV, a long-time admirer invited her to become the only female member of the group of academic elite, he sponsored, called the Benedetti.

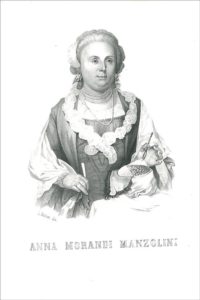

Anna Morandi Manzolini, was another striking figure from this period. Initially an artist, who married and assisted her husband Giovanni Manzolini a professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna, she soon combined the worlds of medical science and art in her outstanding work on anatomical models and study. When at age of 25, Giovanni died of tuberculosis, she took his place as lecturer.

With remarkable skill and artistry, Anna Morandi, created wax models for every aspect of the human body based on her innovative approach to dissection: her models of nervous system, muscular system, the skeleton system, the face and eyes and even the reproductive system became highly prized across Europe and in Russia. These were used in the famous Medical School at Bologna and she herself lectured there from notebooks and models. She was elected as a member of the British Royal Society and she was honoured by the scientifically ambitious heads of State. A fascinating book about the work, by Rebecca Messbarger has helped recover her story: The Lady Anatomist: The Life and Work of Anna Morandi Manzolini.

Maria Gaetana Agnesi, was perhaps the most extensive polymath of all three women and the first woman to publish a mathematics text book and the first female University Professor of mathematics again at Bologna. Maria was part of a step-family of 21 children, and while running the household for her father at the age of 11, was proficient in Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, German and Latin. She gave a paper as a girl, on women’s rights to education. She wrote about differential and integral calculus and about geometry, including the geometry of curves and cones, while privately studying theology.

Pope Benedict XIV appointed her directly to the chair of mathematics, physics and natural philosophy at Bologna, only the second woman professor after Laura Bassi. Instead of taking up this position, she decided to give the rest of her life to the study of theology and to the service of the poor. She was remarkable in choosing to read the Fathers of the Church and not only the devotional writing of the time.

Giving away all her earnings and prizes, she moved into a community of religious sisters in Milan, and it was said that she “… resumed her study of Catholic doctrine and her costly acts of piety towards the poor and suffering, the hopelessly ill and the demented. First in her late father’s house and afterwards in other places she established a hospice for old infirm women.”

Each of the Catholic “hidden” figures obviously combined their human brilliance with what St Edith Stein and Pope Saint John Paul II described as their “feminine genius.” Perhaps it was Maria Agnesi who saw this most clearly. More important than fame or visibility was what Edith Stein saw as the call to every feminine disciple: to develop integrity as a “daughter of God” combined with a mission “to be apostle of the divine Heart.”