Something is amiss when it comes to the ethics of embryo adoption and it has nothing to do with saving the lives of frozen embryos.

In the 6 October issue of The Catholic Weekly Fr John Flader’s weekly column answered a question about the ethical permissibility of an infertile couple (or any couple, for that matter) “adopting” a frozen embryo.

I recommend reading his article, as it includes some great quotes from Dignitas personae (2008), the Instruction on Certain Bioethical Questions given by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

However I do have a concern regarding Fr Flader’s assent to embryo adoption, particularly as I believe the reasons he provides do not adequately address the complex reality a couple will find themselves facing when considering this option – especially the threat it poses to the Catholic understanding of the nature of marriage.

In dealing with the issue of what to do with the large number of frozen embryos already in existence, Dignitas personae points to the Church’s moral objection to using embryos for research or medical treatment purposes.

The document then proceeds to very clearly state that to use embryo adoption as a “treatment for infertility is not ethically acceptable for the same reasons which make artificial heterologous procreation illicit as well as any form of surrogate motherhood.” (DP, 19) (Heterologous artificial procreation is the technique used to obtain a human conception artificially by the use of gametes coming from at least one donor other than the spouses who are joined in marriage).

The document goes on: “It has also been proposed, solely in order to allow human beings to be born who are otherwise condemned to destruction, that there could be a form of “prenatal adoption”. This proposal, praiseworthy with regard to the intention of respecting and defending human life, presents however various problems not dissimilar to those mentioned above.” (DP, 19)

In light of the ambiguity that may be attributed to these statements, and that as yet there is no official Church teaching specifically addressing embryo adoption, I think it’s important to look at what the Church teaches on similar matters, and apply them in context to the present issue at hand. The Church, as our Mother, always asks us to consider Her teachings together, and never in isolation.

The Church’s teaching on marriage and human procreation affirms the “inseparable connection, willed by God and unable to be broken by man on his own initiative, between the two meanings of the conjugal act: the unitive meaning and the procreative meaning. Indeed, by its intimate structure, the conjugal act, while most closely uniting husband and wife, capacitates them for the generation of new lives, according to laws inscribed in the very being of man and of woman.”(Humanae Vitae, 12)

By safeguarding both these essential aspects – the unitive and procreative – the conjugal act preserves in its fullness the very goods of marriage, namely, the unity and indissolubility of marriage, the fidelity of conjugal love and openness to children.

Just as contraception “deliberately deprives the conjugal act of its openness to procreation and in this way brings about a voluntary dissociation of the ends of marriage” (Donum Vitae, II, B, 4a), surely any act that also seeks to separate the unitive from the procreative in an inverse way, also deprives the conjugal act of it’s essential dignity and fidelity: “in seeking a procreation which is not the fruit of a specific act of conjugal union, objectively effects an analogous separation between the goods and the meanings of marriage.” (DV, II, B, 4a)

As a result, “procreation is deprived of its proper perfection when it is not desired as the fruit of the conjugal act,” which the Church defines as “the specific act of the spouses’ union.” (DV, II, B, 4a)

Is it ever permissible then, in Catholic Teaching, to intentionally separate the unitive and procreative aspects of the conjugal act? The Magisterium teaches: “it is never permitted to separate these different aspects to such a degree as positively to exclude either the procreative intention or the conjugal relation.”

Surely, this is what embryo adoption involves – a deliberate and intentional separation of the unitive from the procreative, by seeking the possible gestation of new life (albeit not biologically related to either of the intended parents) to the exclusion of the conjugal union.

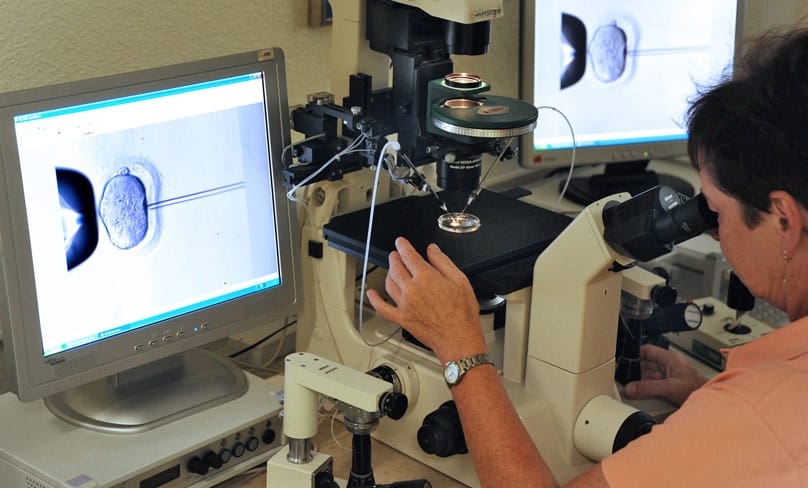

In considering the ethics surrounding IVF, the Church’s moral objection is not merely limited to the in-vitro fertilisation of the egg by the sperm. The Church also opposes how the living embryo is transferred to the uterus of the woman.

A moral correlation here must be made with embryo adoption as this same procedure is involved in both events. The late bioethicist, Professor Nicholas Tonti-Filippini, Australia’s first hospital ethicist, described the process of rescuing embryos as “at best a mistaken, misguided charity though an extraordinarily generous charity.”

However, he concluded “the mistake may be a very grave mistake, striking as it would seem to at the very dignity of the woman and of her marriage.”

Prof Tonti-Filippini reasoned “that having given herself, her psychosomatic unity, faithfully, exclusively, totally, and in a fully human way in marriage (cf. HV 9), a woman is not free to give herself to being impregnated with a child from outside of marriage in this way, however altruistic the purpose and however desperate the plight of those to whom she wishes to give herself.” (The Embryo Rescue Debate, 2003, National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly)

This, I believe, pinpoints the very heart of the debate, and cannot be overlooked.

Should our focus, even one based on charity and a willing generosity, be on saving the lives of frozen embryos at the expense of another grave violation of the sacred union between the spouses? I am not convinced that such an immoral act can ever be justified by the sincerest act of goodwill towards saving the lives of frozen embryos.

One immoral act can never justify another.

And one immoral act can never – and should never – be the solution to a man-made problem.

The salvation of souls is what is at stake – and the risk is too great.

Silvana Scarfe works as Research Assistant to the Most Rev. Richard Umbers, Auxiliary Bishop of Sydney and Bishop Delegate for Life. She is a graduate of the John Paul II Institute for Marriage and the Family and holds a Graduate Diploma in Canonical Practice.